Liberal reforms 60-70 years of the 19th century. New owners of the land

Liberal reforms 60-70 years. 19th century

Goals:

To acquaint students with the reforms of the 60-70s, to show their liberal nature, on the one hand, and limitations, on the other

Tasks:

Tutorials:

Continue work on the disclosure of historical terms and concepts, the formation of chronological knowledge.

Continue work on the formation of special and general educational skills and abilities, such as working with historical document, notebook, didactic card.

Developing:

Develop skills to build, define concepts, analyze, analyze and solve problems

the development of schoolchildren's abilities to establish relationships between historical phenomena;

educators

Raising patriotism for their homeland,

education of work culture

Lesson plan:

Checking homework.

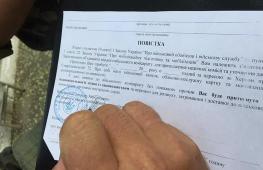

The great chain broke

Broke up and hit

One end on the master,

others - for a man

About what event in question? (peasant reform of 1861)

What are cuts?

What are redemption payments?

What do you think historical meaning peasant reform?

Learning new material.

The abolition of serfdom was followed by other reforms in the field of local self-government, courts, education, censorship, and military affairs, which are commonly called liberal. In the lesson, we will consider three reforms: Zemstvo, judicial reform and military reform. Let us define their main content.

Work with documents by row (5 minutes)

1 row zemstvo reform

2 row - judicial

3rd row - military

In the course of work, students fill out the table “Reforms of the 60-70s. XIX century in Russia"

Judicial

Urban

Discussion: We listen to the answers of the students, then we discuss a number of questions:

Land reform.

In 1864, the zemstvo reform was carried out, which established local self-government bodies in the country. The main contribution to its development was made by N. A. Milyutin and P. A. Valuev

What "concerns" were assigned to the zemstvos? To what extent were self-government bodies independent in their activities?

In the zemstvo school, the emphasis was mainly on the content side of education, on the assimilation by students of a certain amount of knowledge. The parochial school put educational tasks at the forefront, teaching the basics of Orthodoxy and the Russian tradition.

What school do you think the peasant will send his son to and to which of them he will donate money? Why?

In 1865, in 29 provinces, the provincial zemstvo assemblies included 74.2% - nobles and officials, 10.6% - peasants, 10.9% - merchants, 4.3% - other estates. Among the district councilors, 41.7% were represented - nobles and officials, 388.4% - peasants, 10.4% - merchants, 9.5% - other class groups of the population.

Lenin called the zemstvos "the fifth wheel in the cart", but at the same time he recognized that "the zemstvos are a piece of the constitution" confirm that the zemstvos were a representative form of government.

To what extent were the interests of various segments of the population reflected in them?

In 1870, on the model of the zemstvo reform, the reform of urban self-government was carried out, the content of which, you will get to know at home on your own from a textbook.

Judicial reform.

In 1864, another important reform was carried out - the judicial one.

According to one of the active participants in the judicial reform, S. I. Zarudny, “under serfdom, in essence, there was no need for a fair trial. Only the landowners were real judges ... The time has come when for Russia, just like for any decent state, there was an urgent need for a quick and fair court ”

What were the main principles proclaimed by the reform of 1864? what's new in the Russian judicial system?

Why is the question of jurors relevant today?

Judicial reform is rightfully considered the most consistent among the reforms of the 60-70s. However, during its implementation, vestiges of estates were preserved, in particular, the volost court for peasants and corporal punishment for them were preserved.

military reform.

In the middle of the 60s. Minister of War D. A. Milyutin abolished corporal punishment in the army. During the reform of the military educational institutions military gymnasiums and cadet schools were established. The system of higher military education expanded. Finally, in 1874, a new military charter was adopted. Contemporaries called this event February 19, 1861 in the Russian army.

What are the main provisions of the charter, why did contemporaries give such an assessment to the named document?

However, in 1901, Lenin wrote: “In essence, we did not have, and do not have, universal military service, because the privileges of noble birth and wealth create a lot of exceptions.”

Explain what caused such judgments? Argument your opinion.

Explain the following figures: zemstvos were introduced only in 34 provinces of the empire, city dumas - in 509 cities, judicial reform was carried out only in 44 provinces. Why?

Is it fair to call the reforms of the 60-70s. "great"?

How did these transformations affect the daily life of Russian society? How can you explain the words of the historian Klyuchevsky that the reforms, although slow, were sufficiently prepared for implementation, but the minds were less prepared for perception?

Transformations in the Russian Empire in the 60-70s of the century before last are called liberal reforms. The pivotal event of the long-term process was the Great Peasant Reform of 1861. It determined the course of further bourgeois reconstructions and reorganizations taken by the government of Alexander II. It was necessary to reorganize the political superstructure, rebuild the court, the army, and much more.

Thus, Alexander II's understanding of the urgent need for a peasant reform led him to carry out a complex of transformations in all areas during the implementation of the plan. public life Russia. Unwittingly, the emperor himself took steps towards a bourgeois monarchy, which was based on the transition to an industrial society, a market economy and parliamentarism. The assassination of the king in March 1881 turned the country's movement in a different direction.

Military, educational, peasant and judicial reforms were the main transformations carried out in Russia in the 60s and 70s of the century, and thanks to them the country overcame its significant backwardness from the advanced powers.

However, the reforms of Alexander II were not as ideal and did not go as smoothly as it should have been. The aristocratic character of Russian society to a certain extent persisted even after the much-desired liberal reforms were carried out.

What is liberalism

Liberalism is a direction of socio-political and philosophical thought that proclaims human rights and freedoms as the highest value. The influence of the state and other structures, including religion, on a person in a liberal society is usually limited by the constitution. In the economy, liberalism is expressed in the inviolability of private property, freedom of trade and entrepreneurship.

Reasons for liberal reforms

The main reason for liberal reforms is Russia's lagging behind the advanced European countries, which became especially noticeable by the middle of the 19th century. Another reason is the peasant uprisings, the number of which increased sharply by the mid-1850s; popular uprisings threatened the existing state system and autocratic power, so the situation had to be saved.

Prerequisites for reforms

Russian society in all periods of the New Age was very colorful. Completed conservatives here side by side with liberals, zealots of antiquity - with innovators, people with free views; supporters of autocracy tried to get along with adherents of a limited monarchy and republicans. By the middle of the nineteenth century, the contradictions between the "old" and "new" Russians escalated, as a whole galaxy of enlightened nobles grew up, longing for large-scale changes in the country. The imperial house had to make concessions in order to maintain supreme power.

Reform Objectives

The main task of liberal reforms is to overcome the social, political, military and intellectual backwardness of the Russian Empire. Particularly acute was the task of abolishing serfdom, which by that time was morally very outdated, and hindered the economic development of the country. Another task is to show activity precisely “from above”, on the part of the tsarist authorities, until the revolutionaries undertake radical transformations.

Reform of administration of zemstvos and cities

The nobility after the abolition of serfdom was concerned about the strengthening of its role in the political life of the country. The government of the reformers sensitively caught the mood of the ruling class and developed the zemstvo, and a little later, the city reforms.

The reforms were carried out in accordance with the “Regulations on provincial and district local institutions” of January 1, 1864 in 34 provinces of the European part of the empire and the “City Regulations” of June 16, 1870.

Zemstvo reform | urban reform |

|

|---|---|---|

Governing bodies |

|

|

|

|

|

Members of the zemstvo assembly (vowels) were elected every three years by groups of voters (curia):

| Vowels were elected every four years. Three-digit electoral system (small, medium and large taxpayers). Electoral rights had institutions and departments, secular and religious institutions that contributed fees to the city budget. |

The main principles of the zemstvo and city reforms were:

- Separation of local self-government from administrative power.

- Election of governing bodies and all-class representation.

- Independence in financial and economic matters.

Democratic judicial reform

The judiciary, of all liberal reforms, is considered the most consistent. Since 1861, work began on the "Basic provisions for the transformation of the judicial part of Russia." In 1864, the sovereign approved modern judicial charters that defined new principles of legal proceedings:

Organizational principles of the court | The dishonesty of the court. |

Irremovability and independence of judges. |

|

Publicity. |

|

Delimitation of the powers of the courts. |

|

Introduction to the institution of jurors. |

|

Establishment of the institute of forensic investigators. |

|

Introduction to the Institute of Notaries. |

|

Election of individual judicial bodies. |

|

Political investigations are the prerogative of the gendarmerie. |

|

Death sentences can be passed by the Senate and a military court. |

|

Changing the system of punishments (cancellation of stigmatization and corporal punishment for women). |

|

Court system | |

Special. |

The emperor had the right to correct the decisions of all courts through administrative measures.

The overdue reform of the army

The experience of the Crimean War showed that Russia needed a massive army with the necessary reserves and a trained officer corps. The rearmament of the army and the reorganization of the military command and control system are urgently needed. The reform began to be prepared as early as 1861 and was implemented in 1874 with the following steps:

- 15 military districts have been created.

- Establishment of a network of military educational institutions.

- New military regulations have been introduced.

- Equipping the army with new models of weapons.

- Cancellation of the recruiting system.

- The introduction of universal conscription for the recruitment of the army.

As a result, the combat effectiveness of the Russian army increased significantly.

Education reform

Establishment of the "Regulations on Primary Public Schools" of 1864 and the Charter high school solved problems:

- accessibility of education for all classes;

- monopolies of the state and church in the field of education, permission for zemstvos, public associations and individuals to open educational institutions;

- gender equality, the opening of higher courses for women;

- expanding the autonomy of universities.

The reform affected all three educational levels and was significant for the development of the country.

Accompanying reforms

In addition to the landmark reforms, the following were carried out along the way:

The financial reform of 1860 - 1864, which consisted in the transformation of the banking system and the strengthening of the role of the Ministry of Finance.

The tax reform was manifested in the abolition of wine farming, the introduction of indirect taxes and the determination of the limits of zemstvo taxation.

The censorship reform abolished the preview of works, but introduced a system of sanctions after publication.

Liberal reforms of Alexander II: pros and cons

Name of the reform | Essence of reform | ||

|---|---|---|---|

Judicial reform | A unified system of courts was created, while all estates were equal before the law. Court hearings became public and received media coverage mass media. The parties now had the right to use the services of non-state lawyers. | The reform proclaimed the equality of all groups of the population in rights. The attitude of the state towards a person was now formed on the basis of his actions, and not on the origin. | The reform was inconsistent. For the peasants, special volost courts were created with their own system of punishments, which included beatings. If political cases were considered, then administrative repressions were applied even if the verdict was acquittal. |

Zemstvo reform | Changes were made to the system of local self-government. Elections were scheduled for zemstvo and district councils, which were held in two stages. The local government was appointed for a four-year term. | Zemstvos dealt with issues primary education, health care, taxation, etc. Local authorities were given a certain autonomy. | Most of the seats in the zemstvo authorities were occupied by nobles, there were few peasants and merchants. As a result, all issues affecting the interests of the peasants were resolved in favor of the landowners. |

Military reform | Recruitment has been replaced by universal military service, covering all classes. Military districts were created, the main headquarters was founded. | The new system made it possible to reduce the size of the army in peacetime and quickly raise a large army if necessary. A large-scale rearmament has been carried out. A network of military schools was created, education in which was available to representatives of all classes. Corporal punishment in the army has been abolished. | In some cases, corporal punishment was retained - for "fined" soldiers. |

Peasant reform | The personal independence of the peasant was legally established, and he was also given a certain allotment of land for permanent use with the subsequent right of redemption. | Outdated and obsolete serfdom was finally eliminated. There was an opportunity to significantly raise the standard of living of the rural population. Thanks to this, it was possible to eliminate the danger of peasant riots, which became commonplace in the country in the 1850s. The reform made it possible to negotiate with the landowners, who remained full owners of all their land, with the exception of small plots allocated for peasants. | The quitrent was preserved, which the peasants were obliged to pay to the landowner for several years for the right to use the land; |

educational reform | A system of real schools was introduced, in which, unlike classical gymnasiums emphasis on teaching mathematics and natural sciences. A significant number of research laboratories have been established. | The people had the opportunity to receive a versatile and more secular education, to master the sciences in their modern (at that time) state. In addition, higher education courses for women began to open. The advantage for the ruling class was the elimination of the danger of the spread of revolutionary ideas, since young people were now educated in Russia, and not in the west. | Graduates of real schools were restricted from entering higher specialized educational institutions, and they could not enter the university at all. |

urban reform | A system of city self-government was introduced, including city Duma, council and electoral assembly. | The reform allowed the population of cities to equip their urban economy: build roads, infrastructure, credit institutions, marinas, etc. This made it possible to revive the country's commercial and industrial development, as well as to introduce the population to civilian life. | The urban reform was openly nationalistic and confessional in nature. Among the deputies of the city duma, the number of non-Christians should not exceed a third, and the mayor should not have been a Jew. |

Results of reforms

The "great reforms", as they are usually called in historical science, have significantly modernized and modernized Russian empire. The class and property inequality of various segments of the population was significantly smoothed out, although it remained until October revolution. The level of education of the population, including the lower classes, has noticeably increased.

At the same time, clashes escalated between the "enlightened bureaucrats" who developed and implemented reforms, and the aristocratic nobility, who wanted to preserve the old order and their influence in the country. Because of this, Alexander II was forced to maneuver, removing the "enlightened bureaucrats" from business and reappointing them to their posts if necessary.

Significance of reforms

The "great reforms" had a dual meaning, which was originally planned by the tsarist government. On the one hand, the expansion of the rights and freedoms of citizens has improved the social situation in the country; the widespread dissemination of education had a positive impact on the modernization of the Russian economy and contributed to the development of science; military reform made it possible to replace the old, expensive and inefficient army with a more modern one, fully meeting its main tasks and causing minimal harm to the personality of a soldier in peacetime. The "Great Reforms" contributed to the disintegration of the remnants of the feudal system and the development of capitalism in Russia.

On the other hand, the liberal reforms strengthened the strength and authority of autocratic power and made it possible to combat the spread of radical revolutionary ideas. It just so happened that the most faithful supporters of unlimited royal power were precisely the liberal “enlightened bureaucrats”, and not the arrogant aristocratic elite. Education had a special role to play: young people had to be taught to think seriously in order to prevent the formation of superficial radical views in their minds.

World-historical theory

materialist historians(I. A. Fedosov and others) define the period of the abolition of serfdom as a sharp transition from a feudal socio-economic formation to a capitalist one. They believe that the abolition of serfdom in Russia late, and the reforms that followed it were carried out slowly and incompletely. Half-heartedness in carrying out reforms caused indignation of the advanced part of society- the intelligentsia, which then resulted in terror against the king. Marxist revolutionaries believed that the country was "led" along the wrong path of development- "slow cutting off the rotting parts", but it was necessary to "lead" along the path of a radical solution of problems - the confiscation and nationalization of landowners' lands, the destruction of the autocracy, etc.

liberal historians, contemporaries of events, V.O. Klyuchevsky (1841-1911), S.F. Platonov (1860-1933) and others, welcomed both the abolition of serfdom and subsequent reforms. Defeat in Crimean War, they believed, revealed technical lag of Russia from W apad and undermined the international prestige of the country.

Later liberal historians ( I. N. Ionov, R. Pipes and others) began to note that in In the middle of the 19th century, serfdom reached the highest point of economic efficiency. The reasons for the abolition of serfdom are political. The defeat of Russia in the Crimean War dispelled the myth of the military power of the Empire, caused irritation in society and a threat to the stability of the country. The interpretation focuses on the price of reforms. Thus, the people were not historically prepared for drastic socio-economic changes and "painfully" perceived the changes in their lives. The government did not have the right to abolish serfdom and carry out reforms without comprehensive social and moral preparation of the entire people, especially nobles and peasants. According to liberals, the centuries-old way of Russian life cannot be changed by force.

ON THE. Nekrasov in the poem “To whom it is good to live in Russia” writes:

The great chain is broken

broke and hit:

one end along the master,

others - like a man! ...

Historians of the technological direction (V. A. Krasilshchikov, S. A. Nefedov, etc.) believe that the abolition of serfdom and subsequent reforms are due to the stage of Russia's modernization transition from a traditional (agrarian) society to an industrial one. The transition from traditional to industrial society in Russia was carried out by the state during the period of influence from the 17th-18th centuries. European cultural and technological circle (modernization - westernization) and acquired the form of Europeanization, that is, a conscious change in traditional national forms according to the European model.

“Machine” progress v Western Europe“forced” tsarism to actively impose an industrial order. And this determined the specifics of modernization in Russia. The Russian state, while selectively borrowing technical and organizational elements from the West, simultaneously conserved traditional structures. As a result, the country has situation of “overlapping of historical epochs”(industrial - agrarian), which later led to social shocks.

Industrial society introduced by the state at the expense of the peasants, came into sharp conflict with all the fundamental conditions of Russian life and was bound to give rise to protest both against the autocracy, which did not give the desired freedom to the peasant, and against the private owner, a figure previously alien to Russian life. The industrial workers who appeared in Russia as a result of industrial development inherited the hatred of the entire Russian peasantry, with its centuries-old communal psychology, for private property.

Tsarism is interpreted as a regime that was forced to begin industrialization, but failed to cope with its consequences.

Local historical theory.

The theory is represented by the works of Slavophiles and Narodniks. Historians believed that Russia, unlike Western countries, follows its own, special path of development. They substantiated the possibility in Russia of a non-capitalist path of development to socialism through the peasant community.

Reforms of Alexander II

Land reform. Main question in Russia during the XVIII-XIX centuries there was a land-peasant. Catherine II raised this question in the work of Volny economic society, which reviewed several dozen programs for the abolition of serfdom, both Russian and foreign authors. Alexander I issued a decree "On free cultivators", allowing landowners to free their peasants from serfdom along with land for ransom. Nicholas I during the years of his reign, he created 11 secret committees on the peasant question, whose task was the abolition of serfdom, the solution of the land issue in Russia.

In 1857, by decree of Alexander II started to work secret committee on the peasant question, the main task of which was the abolition of serfdom with the obligatory allocation of land to the peasants. Then such committees were created for the provinces. As a result of their work (and the wishes and orders of both landlords and peasants were taken into account) was a reform was developed to abolish serfdom for all regions of the country, taking into account local specifics. For different areas were the maximum and minimum values of the allotment transferred to the peasant are determined.

Emperor February 19, 1861 signed a number of laws. Was here Manifesto and Regulations on the Granting of Freedom to the Peasants us, documents on the entry into force of the Regulations, on the management of rural communities, etc.

Abolition of serfdom was not a one-time event. First, the landlord peasants were released, then the specific and assigned to the factories. Peasants got personal freedom, but the land remained the property of the landowners, and while allotments were assigned, the peasants were in the position of "temporarily liable" carried duties in favor of the landowners, which in essence did not differ from the former, serfs. The plots handed over to the peasants were, on average, 1/5 less than those that they cultivated before. To these lands purchase agreements were signed, after that the "temporarily liable" state ceased, the treasury paid off for the land with the landlords, the peasants - with the treasury for 49 years at the rate of 6% per annum (redemption payments).

Land use, relations with the authorities were built through the community. She kept as a guarantor of peasant payments. The peasants were attached to society (the world).

As a result of reforms serfdom was abolished- that “obvious and tangible evil for everyone”, which in Europe was directly called “ Russian slavery. However, the land problem was not resolved, since the peasants, when dividing the land, were forced to give the landlords a fifth of their allotments.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the first Russian revolution broke out in Russia, a peasant revolution in many respects in terms of the composition of the driving forces and the tasks that confronted it. This is what made P.A. Stolypin to implement land reform, allowing the peasants to leave the community. The essence of the reform was to resolve the land issue, but not through the confiscation of land from the landlords, as the peasants demanded, but through the redistribution of the land of the peasants themselves.

Liberal reforms of the 60-70s

Zemstvo and city reforms. The principle carried out in 1864. zemstvo reform was electiveness and ignorance. In the provinces and districts of Central Russia and part of Ukraine Zemstvos were established as local self-government bodies. Elections to zemstvo assemblies were carried out on the basis of property, age, educational and a number of other qualifications. Women and employees were denied the right to vote. This gave an advantage to the wealthiest segments of the population. Assemblies elected zemstvo councils. Zemstvos were in charge affairs of local importance, promoted entrepreneurship, education, health care - carried out work for which the state did not have funds.

Held in 1870 urban reform in character was close to the zemstvo. In major cities city councils were established on the basis of all-class elections. However, elections were held on a census basis, and, for example, in Moscow only 4% of the adult population participated in them. City councils and the mayor decided issues of internal self-government, education and health care. For control for zemstvo and city activities was created presence on city affairs.

Judicial reform. Newjudicial statutes were approved on November 20, 1864. Judicial power was separated from the executive and legislative. A classless and public court was introduced, the principle of the irremovability of judges was affirmed. Two types of court were introduced - general (crown) and world. The general court was in charge of criminal cases. The trial became open, although in a number of cases cases were heard behind closed doors. The competitiveness of the court was established, the positions of investigators were introduced, the bar was established. The question of the guilt of the defendant was decided by 12 jurors. The most important principle of the reform was the recognition of the equality of all subjects of the empire before the law.

For the analysis of civil cases was introduced institute of magistrates. Appellate authority for the courts were judicial chambers you. position was introduced notary. Since 1872, major political cases were considered in Special Presence of the Governing Senate which became at the same time the highest instance of cassation.

military reform. After his appointment in 1861, D.A. Milyutin as Minister of War begins the reorganization of the command and control of the armed forces. In 1864, 15 military districts were formed, directly subordinate to the Minister of War. In 1867, a military-judicial charter was adopted. In 1874, after a long discussion, the tsar approved the Charter on universal military service. A flexible conscription system was introduced. Recruitment was canceled, the entire male population over the age of 21 was subject to conscription. The term of service was reduced in the army to 6 years, in the navy to 7 years. Clerics, members of a number of religious sects, the peoples of Kazakhstan and Central Asia, as well as some peoples of the Caucasus and the Far North. The only son, the only breadwinner in the family, was released from service. In peacetime, the need for soldiers was much less than the number of conscripts, so all those fit for service, with the exception of those who received benefits, drew lots. For those who graduated from elementary school, the service was reduced to 3 years, for those who graduated from a gymnasium - up to 1.5 years, a university or institute - up to 6 months.

financial reform. In 1860 was the State Bank was established, happened cancellation of the pay-off 2 system, which was replaced by excises 3(1863). Since 1862 the only responsible manager of budget revenues and expenditures was the Minister of Finance; the budget is made public. Was made attempt at currency reform(free exchange of credit notes for gold and silver at the established rate).

Education reforms. "Regulations on Primary Public Schools" of June 14, 1864 liquidated the state-church monopoly on education. Now both public and private institutions were allowed to open and maintain elementary schools. persons under the control of district and provincial school councils and inspectors. The charter of the secondary school introduced the principle of equality of all classes and religions. y, but introduced tuition fee.

Gymnasiums were divided into classical and real nye. In classical gymnasiums, humanitarian disciplines were mainly taught, in real ones - natural ones. After the resignation of the Minister of Public Education A.V. Golovnin (in 1861 D.A. Tolstoy was appointed instead of him) was accepted new gymnasium charter, retaining only classical gymnasiums, real gymnasiums were replaced by real schools. Along with male secondary education there was a system of women's gymnasiums.

University Us tav (1863) provided Universities had broad autonomy, elections of rectors and professors were introduced. School management handed over to the Council of Prof. Essorov, to whom the students were subordinate. Were Universities were opened in Odessa and Tomsk, higher courses for women were opened in St. Petersburg, Kiev, Moscow, Kazan.

As a result of the publication of a number of laws in Russia, a harmonious education system was created, including primary, secondary and higher educational institutions.

Censorship reform. In May 1862 censorship reform began, were introduced "temporary rules”, which in 1865 was replaced by a new censorship charter. Under the new charter, preliminary censorship was abolished for books of 10 or more printed sheets (240 pages); editors and publishers could only be prosecuted in court. Periodical publications were also exempted from censorship by special permission and upon payment of a deposit of several thousand rubles, but they could be suspended administratively. Only government and scientific publications, as well as literature translated from a foreign language, could be published without censorship.

The preparation and implementation of reforms were an important factor in the socio-economic development of the country. Administrative reforms were quite well prepared, but public opinion did not always keep pace with the ideas of the reformer tsar. The variety and speed of transformations gave rise to a feeling of uncertainty and confusion in thoughts. People lost their bearings, organizations appeared, professing extremist, sectarian principles.

For economy post-reform Russia is characterized fast development commodity-money relations. noted growth in acreage and agricultural production, but performance Agriculture remained low. Yields and food consumption (except for bread) were 2-4 times lower than in Western Europe. At the same time, in the 1980s compared to the 50s. the average annual grain harvest increased by 38%, and its export increased by 4.6 times.

The development of commodity-money relations led to property differentiation in the countryside, the middle peasant farms were ruined, the number of poor peasants grew. On the other side, strong kulak farms appeared, some of which used agricultural machinery. All this was part of the plans of the reformers. But quite unexpectedly for them in the country the traditionally hostile attitude towards trade That is, to all new forms of activity: to the kulak, the merchant, the fence - to the successful entrepreneur.

In Russia large-scale industry was created and developed as a state. The main concern of the government after the failures of the Crimean War were enterprises that produced military equipment. The military budget of Russia in general terms was inferior to the English, French, German, but in the Russian budget it had more significant weight. Special attention applied to development of heavy industry and transport. It was in these areas that the government directed funds, both Russian and foreign.

The growth of entrepreneurship was controlled by the state on the basis of the issuance of special orders, That's why the big bourgeoisie was closely connected with the state. Quickly an increase in the number of industrial workers However, many workers retained economic and psychological ties with the countryside, they carried a charge of discontent among the poor who lost their land and were forced to seek food in the city.

The reforms laid the foundation new system loan. For 1866-1875. It was 359 joint-stock commercial banks, mutual credit societies and other financial institutions have been established. Since 1866, they began to actively participate in their work. major European banks. As a result of state regulation, foreign loans and investments went mainly to railway construction. Railways ensured the expansion of the economic market in the vast expanses of Russia; they were also important for the operational transfer of military units.

In the second half of the 19th century, the political situation in the country changed several times.

During the preparation of the reforms, from 1855 to 1861, the government retained the initiative of action, attracted all the supporters of the reforms - from the highest bureaucracy to the democrats. Subsequently, the difficulties with reforms exacerbated the domestic political situation in the country. The struggle of the government against opponents from the "left" acquired a cruel character: the suppression of peasant uprisings, the arrests of liberals, the defeat of the Polish uprising. The role of the III Security (gendarme) department was strengthened.

V 1860s radical movement entered the political arena populists. Raznochintsy intelligentsia, based on revolutionary democratic ideas and nihilism DI. Pisarev, created the theory of revolutionary populism. The populists believed in the possibility of achieving socialism, bypassing capitalism, through the liberation of the peasant community - the rural "peace". "Rebel" M.A. Bakunin predicted a peasant revolution, the fuse of which was to be lit by the revolutionary intelligentsia. P.N. Tkachev was the theorist of a coup d'état, after which the intelligentsia, having carried out the necessary transformations, would liberate the community. P.L. Lavrov substantiated the idea of thorough preparation of the peasants for the revolutionary struggle. V 1874 began a mass "going to the people”, but the agitation of the populists failed to ignite the flame of a peasant uprising.

In 1876 arose organization "Land and freedom", which in 1879 split into two groups.

Group " Black redistribution” headed by G.V. Plekhanov focused on propaganda;

« Narodnaya Volya” headed by A.I. Zhelyabov, N.A. Morozov, S.L. Perovskaya in brought to the fore political struggle. The main means of struggle, in the opinion of the Narodnaya Volya, was individual terror, regicide, which was supposed to serve as a signal to popular uprising. In 1879-1881. Narodnaya Volya held a series assassination attempt on Alexander II.

In a situation of acute political confrontation, the authorities embarked on the path of self-defense. February 12, 1880 was established "Supreme Administrative Commission for the Protection of State Order and Public Peace» headed by M.P. Loris-Melikov. Having received unlimited rights, Loris-Melikov achieved a suspension of the terrorist activities of the revolutionaries and some stabilization of the situation. In April 1880 the commission was liquidated; Loris-Melikov was appointed Minister of the Interior and began to prepare the completion of the "great cause of state reforms". The drafting of the final reform laws was entrusted to the "people" - temporary preparatory commissions with a wide representation of zemstvos and cities.

On February 5, 1881, the submitted bill was approved by Emperor Alexander II. " Constitution of Loris-Melikov” provided for the election of “representatives from public institutions ...” to the highest bodies of state power. In the morning March 1, 1881 the emperor appointed a meeting of the Council of Ministers to approve the bill; in just a few hours Alexander II was killed members of the People's Will organization.

New emperor Alexander III March 8, 1881 held a meeting of the Council of Ministers to discuss the Loris-Melikov project. At the meeting, the Chief Prosecutor of the Holy Synod K.P. Pobedonostsev and head of the State Council S.G. Stroganov. The resignation of Loris-Melikov soon followed.

V May 1883 Alexander III proclaimed a course called in the historical-materialist literature " counter-reforms», and in the liberal-historical one - "adjustment of reforms". He expressed himself as follows.

In 1889, to strengthen supervision over the peasants, the positions of zemstvo chiefs with broad rights were introduced. They were appointed from local landowning nobles. The clerks and small merchants, other poor sections of the city, lost their suffrage. Judicial reform has undergone a change. In the new regulation on the zemstvos of 1890, the representation of estates and nobility was strengthened. In 1882-1884. many publications were closed, the autonomy of universities was abolished. Primary schools were transferred to the church department - the Synod.

These activities showed the idea of an "official nation"» times of Nicholas I - the slogan « Orthodoxy. Autocracy. Spirit of Humility was consonant with the slogans of a bygone era. The new official ideologists of K.P. Pobedonostsev (Chief Prosecutor of the Synod), M.N. Katkov (editor of Moskovskie Vedomosti), Prince V. Meshchersky (publisher of the newspaper Grazhdanin) omitted the word "people" from the old formula "Orthodoxy, autocracy and the people" as "dangerous"; they preached the humility of his spirit before the autocracy and the church. In practice, the new policy resulted in an attempt to strengthen the state by relying on the traditionally loyal to the throne nobility. Administrative measures were reinforced economic support for landowners.

peasant reform. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .one

Liberal reforms 60-70s. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4

Establishment of zemstvos . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .4

Self-government in cities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6

Judicial reform . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Military reform . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

Education reforms . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ....10

Church in the period of reforms. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11 Conclusion. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. . . . . . . . . .thirteen

Peasant reform .

Russia on the eve of the abolition of serfdom . The defeat in the Crimean War testified to the serious military-technical lag of Russia from the leading European states. There was a threat of the country sliding into the category of minor powers. The government could not allow this. With defeat came the realization that main reason Russia's economic backwardness was serfdom.

The enormous costs of the war seriously undermined the monetary system of the state. Recruitment, the seizure of livestock and fodder, the growth of duties ruined the population. And although the peasants did not respond to the hardships of the war with mass uprisings, they were in a state of intense expectation of the tsar's decision to abolish serfdom.

In April 1854, a decree was issued on the formation of a reserve rowing flotilla ("sea militia"). With the consent of the landowner and with a written obligation to return to the owner, serfs could also be recorded in it. The decree limited the flotilla formation area to four provinces. However, he stirred up almost all of peasant Russia. Word spread in the villages that the emperor was calling for volunteers for military service and for this forever frees them from serfdom. Unauthorized registration in the militia resulted in a mass exodus of peasants from the landowners. This phenomenon took on an even broader character in connection with the manifesto of January 29, 1855, on the recruitment of warriors into the land militia, covering dozens of provinces.

The atmosphere in the "enlightened" society has also changed. According to the figurative expression of the historian V. O. Klyuchevsky, Sevastopol hit stagnant minds. “Now the question of the emancipation of serfs is on everyone’s lips,” wrote the historian K. D. Kavelin, “they talk about it loudly, even those who previously could not hint at the fallibility of serfdom without causing nervous attacks think about it.” Even the relatives of the king, his aunt, grand duchess Elena Pavlovna, and younger brother Konstantin.

Preparation of the peasant reform . For the first time, on March 30, 1856, Alexander II officially announced the need to abolish serfdom to representatives of the Moscow nobility. At the same time, knowing the mood of the majority of the landowners, he emphasized that it is much better if this happens from above than to wait until it happens from below.

On January 3, 1857, Alexander II formed a Secret Committee to discuss the issue of abolishing serfdom. However, many of its members, former Nicholas dignitaries, were ardent opponents of the liberation of the peasants. They hindered the work of the committee in every possible way. And then the emperor decided to take more effective measures. At the end of October 1857, Vilna Governor-General VN Nazimov arrived in St. Petersburg, who in his youth was Alexander's personal adjutant. He brought the appeal of the nobles of the Vilna, Kovno and Grodno provinces to the emperor. They asked permission to discuss the issue of freeing the peasants without giving them land. Alexander took advantage of this request and on November 20, 1857, sent Nazimov a rescript on the establishment of provincial committees from among the landlords to prepare draft peasant reforms. On December 5, 1857, St. Petersburg Governor-General P. I. Ignatiev received a similar document. Soon the text of the rescript sent to Nazimov appeared in the official press. Thus, the preparation of the peasant reform became public.

During 1858, "committees for improving the life of landlord peasants" were established in 46 provinces (officials were afraid to include the word "liberation" in official documents). In February 1858, the Secret Committee was renamed the Main Committee. Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich became its chairman. In March 1859 Editorial Commissions were established under the Main Committee. Their members were engaged in the consideration of materials coming from the provinces, and drawing up on their basis a general draft law on the emancipation of the peasants. General Ya. I. Rostovtsev, who enjoyed the emperor's special confidence, was appointed chairman of the commissions. He attracted to his work supporters of reforms from among the liberal officials and landowners - N. A. Milyutin, Yu. F. Samarin, V. A. Cherkassky, Ya. ". They advocated the release of the peasants with a land allotment for redemption and their transformation into small landowners, while the landownership was preserved. These ideas were fundamentally different from those expressed by the nobles in the provincial committees. They believed that even if the peasants were to be liberated, then without land. In October 1860, the editorial commissions completed their work. The final preparation of the reform documents was transferred to the Main Committee, then they were approved by the State Council.

The main provisions of the peasant reform. On February 19, 1861, Alexander II signed a manifesto “On granting serfs the rights of the status of free rural inhabitants and on the organization of their life”, as well as the “Regulations on peasants who emerged from serfdom”. According to these documents, the peasants, who previously belonged to the landlords, were declared legally free and received general civil rights. When they were released, they were given land, but in a limited amount and for ransom on special conditions. The land allotment, which the landowner provided to the peasant, could not be higher than the norm established by law. Its size ranged from 3 to 12 acres in various parts of the empire. If by the time of liberation there was more land in peasant use, then the landowner had the right to cut off the surplus, while land was taken from the peasants best quality. According to the reform, the peasants had to buy the land from the landowners. They could get it for free, but only a quarter of the allotment determined by law. Until the redemption of their land plots, the peasants found themselves in the position of temporarily liable. They had to pay dues or serve corvee in favor of the landowners.

The size of allotments, dues and corvées were to be determined by an agreement between the landowner and the peasants - Charters. The temporary state could last for 9 years. At this time, the peasant could not give up his allotment.

The amount of the ransom was determined in such a way that the landowner would not lose the money that he had previously received in the form of dues. The peasant had to immediately pay him 20-25% of the value of the allotment. To enable the landowner to receive the redemption sum at a time, the government paid him the remaining 75-80%. The peasant, on the other hand, had to repay this debt to the state for 49 years with an accrual of 6% per annum. At the same time, calculations were made not with each individual, but with the peasant community. Thus, the land was not the personal property of the peasant, but the property of the community.

Peace mediators, as well as provincial presences for peasant affairs, consisting of the governor, government official, prosecutor and representatives of local landowners, were supposed to monitor the implementation of the reform on the ground.

The reform of 1861 abolished serfdom. The peasants became free people. However, the reform preserved serfdom remnants in the countryside, primarily landownership. In addition, the peasants did not receive full ownership of the land, which means they did not have the opportunity to rebuild their economy on a capitalist basis.

Liberal reforms of the 60-70s

Establishment of zemstvos . After the abolition of serfdom, a number of other transformations were required. By the beginning of the 60s. the former local administration showed its complete failure. The activities of the officials appointed in the capital who led the provinces and districts, and the detachment of the population from making any decisions, brought economic life, health care, and education to extreme disorder. The abolition of serfdom made it possible to involve all segments of the population in solving local problems. At the same time, when establishing new governing bodies, the government could not ignore the moods of the nobles, many of whom were dissatisfied with the abolition of serfdom.

On January 1, 1864, an imperial decree introduced the "Regulations on provincial and district zemstvo institutions", which provided for the creation of elective zemstvos in the counties and provinces. Only men had the right to vote in the elections of these bodies. Voters were divided into three curia (categories): landowners, city voters and elected from peasant societies. Owners of at least 200 acres of land or other real estate in the amount of at least 15 thousand rubles, as well as owners of industrial and commercial enterprises that generate income of at least 6 thousand rubles a year, could be a voter in the landowning curia. The small landowners, uniting, put forward only representatives in the elections.

The voters of the city curia were merchants, owners of enterprises or trading establishments with an annual turnover of at least 6 thousand rubles, as well as owners of real estate in the amount of 600 rubles (in small towns) to 3.6 thousand rubles (in major cities).

Elections but the peasant curia were multi-stage: at first, rural assemblies elected representatives to volost assemblies. Electors were first elected at volost gatherings, who then nominated representatives to county self-government bodies. At district assemblies, representatives from the peasants were elected to the provincial self-government bodies.

Zemstvo institutions were divided into administrative and executive. Administrative bodies - zemstvo assemblies - consisted of vowels of all classes. Both in the counties and in the provinces, vowels were elected for a period of three years. Zemstvo assemblies elected executive bodies - zemstvo councils, which also worked for three years. The range of issues that were resolved by zemstvo institutions was limited to local affairs: the construction and maintenance of schools, hospitals, the development of local trade and industry, and so on. The legitimacy of their activities was monitored by the governor. The material basis for the existence of zemstvos was a special tax, which was imposed on real estate: land, houses, factories and trade establishments.

The most energetic, democratically minded intelligentsia grouped around the zemstvos. The new self-government bodies raised the level of education and public health, improved the road network and expanded agronomic assistance to the peasants on such a scale that government was incapable. Despite the fact that representatives of the nobility prevailed in the zemstvos, their activities were aimed at improving the situation of the broad masses of the people.

Zemstvo reform was not carried out in the Arkhangelsk, Astrakhan and Orenburg provinces, in Siberia, in Central Asia - where there was no noble land ownership or was insignificant. Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Right-Bank Ukraine, and the Caucasus did not receive local governments, since there were few Russians among the landowners.

self-government in cities. In 1870, following the example of the Zemstvo, a city reform was carried out. It introduced all-estate self-government bodies - city dumas, elected for four years. Vowels of the Dumas elected for the same term permanent executive bodies - city councils, as well as the mayor, who was the head of both the thought and the council.

The right to choose new governing bodies was enjoyed by men who had reached the age of 25 and paid city taxes. All voters, in accordance with the amount of fees paid in favor of the city, were divided into three curia. The first was a small group of the largest owners of real estate, industrial and commercial enterprises, who paid 1/3 of all taxes to the city treasury. The second curia included smaller taxpayers contributing another 1/3 of the city fees. The third curia consisted of all other taxpayers. At the same time, each of them elected an equal number of vowels to the city duma, which ensured the predominance of large owners in it.

The activity of city self-government was controlled by the state. The mayor was approved by the governor or the minister of the interior. The same officials could impose a ban on any decision of the city duma. To control the activities of city self-government in each province, a special body was created - the provincial presence for city affairs.

City self-government bodies appeared in 1870, first in 509 Russian cities. In 1874, the reform was introduced in the cities of Transcaucasia, in 1875 - in Lithuania, Belarus and Right-Bank Ukraine, in 1877 - in the Baltic states. It did not apply to the cities of Central Asia, Poland and Finland. For all the limitations, the urban reform of the emancipation of Russian society, like the Zemstvo one, contributed to the involvement of broad sections of the population in solving management issues. This served as a prerequisite for the formation of civil society and the rule of law in Russia.

Judicial reform . The most consistent transformation of Alexander II was the judicial reform carried out in November 1864. In accordance with it, the new court was built on the principles of bourgeois law: the equality of all classes before the law; publicity of the court"; independence of judges; competitiveness of prosecution and defense; irremovability of judges and investigators; electivity of some judicial bodies.

According to the new judicial statutes, two systems of courts were created - world and general. The magistrates' courts heard petty criminal and civil cases. They were created in cities and counties. Justices of the peace administered justice alone. They were elected by zemstvo assemblies and city councils. High educational and property qualifications were established for judges. At the same time, they received rather high wages - from 2200 to 9 thousand rubles a year.

The system of general courts included district courts and judicial chambers. Members of the district court were appointed by the emperor on the proposal of the Minister of Justice and considered criminal and complex civil cases. Consideration of criminal cases took place with the participation of twelve jurors. The juror could be a citizen of Russia aged 25 to 70 with an impeccable reputation, living in the area for at least two years and owning real estate in the amount of 2,000 rubles or more. Jury lists were approved by the governor. Appeals against the District Court's decision were made to the Trial Chamber. Moreover, an appeal against the verdict was allowed. The Judicial Chamber also considered cases of malfeasance of officials. Such cases were equated with state crimes and were heard with the participation of class representatives. The highest court was the Senate. The reform established publicity litigation. They were held openly, in the presence of the public; newspapers printed reports on trials of public interest. The competitiveness of the parties was ensured by the presence at the trial of the prosecutor - the representative of the prosecution and the lawyer defending the interests of the accused. In Russian society, there was an extraordinary interest in advocacy. Outstanding lawyers F. N. Plevako, A. I. Urusov, V. D. Spasovich, K. K. Arseniev, who laid the foundations of the Russian school of lawyer-orators, became famous in this field. The new judicial system retained a number of vestiges of estates. These included volost courts for peasants, special courts for the clergy, military and senior officials. In some national areas, the implementation of judicial reform dragged on for decades. In the so-called Western Territory (Vilna, Vitebsk, Volyn, Grodno, Kiev, Kovno, Minsk, Mogilev and Podolsk provinces), it began only in 1872 with the creation of magistrates' courts. Justices of the peace were not elected, but appointed for three years. District courts began to be created only in 1877. At the same time, Catholics were forbidden to hold judicial office. In the Baltics, the reform began to be implemented only in 1889.

Only in late XIX v. judicial reform was carried out in the Arkhangelsk province and Siberia (in 1896), as well as in Central Asia and Kazakhstan (in 1898). Here, too, the appointment of magistrates took place, who simultaneously performed the functions of investigators, the jury trial was not introduced.

military reforms. Liberal transformations in society, the desire of the government to overcome backwardness in the military field, as well as to reduce military spending, necessitated fundamental reforms in the army. They were conducted under the leadership of Minister of War D. A. Milyutin. In 1863-1864. reform of military educational institutions began. General education It was separated from the special one: future officers received general education in military gymnasiums, and professional training in military schools. The children of the nobility studied mainly in these educational institutions. For those who did not have a secondary education, cadet schools were created, where representatives of all classes were admitted. In 1868, military progymnasiums were created to replenish the cadet schools.

In 1867 the Military Law Academy was opened, in 1877 Marine Academy. Instead of recruitment sets, all-class military service was introduced. According to the charter approved on January 1, 1874, persons of all classes from the age of 20 (later - from the age of 21) were subject to conscription. The total service life for the ground forces was set at 15 years, of which 6 years - active service, 9 years - in reserve. In the fleet - 10 years: 7 - valid, 3 - in reserve. For persons who received an education, the term of active service was reduced from 4 years (for those who graduated from elementary schools) to 6 months (for those who received higher education).

The only sons and the only breadwinners of the family were released from service, as well as those recruits whose older brother was serving or had already served a term of active service. Those exempted from conscription were enlisted in the militia, which was formed only during the war. Clerics of all faiths, representatives of some religious sects and organizations, the peoples of the North, Central Asia, part of the inhabitants of the Caucasus and Siberia were not subject to conscription. Corporal punishment was abolished in the army, punishment with rods was retained only for fines), food was improved, barracks were re-equipped, and literacy was introduced for soldiers. There was a rearmament of the army and navy: smooth-bore weapons were replaced by rifled ones, the replacement of cast-iron and bronze guns with steel ones began; The rapid-fire rifles of the American inventor Berdan were adopted for service. The system of combat training has changed. A number of new statutes, instructions, teaching aids, who set the task of teaching soldiers only what is needed in the war, significantly reducing the time for drill training.

As a result of the reforms, Russia received a massive army that met the requirements of the times. The combat readiness of the troops has significantly increased. The transition to universal military service was a serious blow to the class organization of society.

Reforms in the field of education. The education system has also undergone a significant restructuring. In June 1864, the "Regulations on Primary Public Schools" were approved, according to which such educational institutions could be opened by public institutions and private individuals. This led to the creation primary schools various types- state, zemstvo, parish, Sunday, etc. The term of study in them did not exceed, as a rule three years.

Since November 1864, gymnasiums have become the main type of educational institution. They were divided into classical and real. In the classical, a large place was given to the ancient languages - Latin and Greek. The term of study in them was at first seven years, and from 1871 - eight years. Graduates of classical gymnasiums had the opportunity to enter universities. Six-year real gymnasiums were designed to prepare "for employment in various branches of industry and trade."

The main attention was paid to the study of mathematics, natural science, technical subjects. Access to universities for graduates of real gymnasiums was closed, they continued their studies in technical institutes. The foundation was laid for women's secondary education - women's gymnasiums appeared. But the amount of knowledge given in them was inferior to what was taught in male gymnasiums. The gymnasium accepted children "of all classes, without distinction of rank and religion", however, at the same time, high tuition fees were set. In June 1864, a new charter for the universities was approved, restoring the autonomy of these educational institutions. The direct management of the university was entrusted to the council of professors, who elected the rector and deans, approved educational plans dealt with financial and personnel issues. Women's higher education began to develop. Since gymnasium graduates did not have the right to enter universities, higher women's courses were opened for them in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Kazan, and Kiev. Women began to be admitted to universities, but as volunteers.

Orthodox Church in the period of reforms. Liberal reforms affected and Orthodox Church. First of all, the government tried to improve the financial situation of the clergy. In 1862, a Special Presence was created to find ways to improve the life of the clergy, which included members of the Synod and senior officials of the state. Public forces were also involved in solving this problem. In 1864, parish guardianships arose, consisting of parishioners, who not only focused on the study of mathematics, natural science, and technical subjects. Access to universities for graduates of real gymnasiums was closed, they continued their studies at technical institutes.

The foundation was laid for women's secondary education - women's gymnasiums appeared. But the amount of knowledge given in them was inferior to what was taught in the men's gymnasiums. The gymnasium accepted children "of all classes, without distinction of rank and religion", however, at the same time, high tuition fees were set.

In June 1864, a new charter for the universities was approved, restoring the autonomy of these educational institutions. The direct management of the university was entrusted to the council of professors, who elected the rector and deans, approved curricula, and resolved financial and personnel issues. Women's higher education began to develop. Since gymnasium graduates did not have the right to enter universities, higher women's courses were opened for them in Moscow, St. Petersburg, Kazan, and Kiev. Women began to be admitted to universities, but as volunteers.

Orthodox Church in the period of reforms. Liberal reforms also affected the Orthodox Church. First of all, the government tried to improve the financial situation of the clergy. In 1862, a Special Presence was created to find ways to improve the life of the clergy, which included members of the Synod and senior officials of the state. Public forces were also involved in solving this problem. In 1864, parish guardianships arose, consisting of parishioners, who not only managed the affairs of the parish, but also had to help improve the financial situation of clergy. In 1869-79. incomes of parish priests increased significantly due to the abolition of small parishes and the establishment of an annual salary, which ranged from 240 to 400 rubles. Old-age pensions were introduced for the clergy.

The liberal spirit of the reforms carried out in the field of education also touched church educational institutions. In 1863, graduates of theological seminaries received the right to enter universities. In 1864, the children of the clergy were allowed to enroll in gymnasiums, and in 1866, in military schools. In 1867, the Synod passed resolutions on the abolition of the heredity of parishes and on the right to enter seminaries for all Orthodox without exception. These measures destroyed class partitions and contributed to the democratic renewal of the clergy. At the same time, they led to the departure from this environment of many young, gifted people who joined the ranks of the intelligentsia. Under Alexander II, the legal recognition of the Old Believers took place: they were allowed to register their marriages and baptisms in civil institutions; they could now hold certain public positions and freely travel abroad. At the same time, in all official documents, adherents of the Old Believers were still called schismatics, they were forbidden to occupy public office.

Conclusion: During the reign of Alexander II in Russia, liberal reforms were carried out that affected all aspects of public life. Thanks to the reforms, significant segments of the population received the initial skills of management and public work. The reforms laid down traditions, albeit very timid ones, of civil society and the rule of law. At the same time, they retained the estate advantages of the nobles, and also had restrictions for the national regions of the country, where the free popular will determines not only the law, but also the personality of the rulers, in such a country political assassination as a means of struggle is a manifestation of the same spirit of despotism, the destruction of which in We set Russia as our task. The despotism of the individual and the despotism of the party are equally reprehensible, and violence is justified only when it is directed against violence.” Comment on this document.

The emancipation of the peasants in 1861 and the subsequent reforms of the 1960s and 1970s became a turning point in Russian history. This period was called the era of "great reforms" by liberal figures. Their result was the creation necessary conditions for the development of capitalism in Russia, which allowed her to go the pan-European path.

The pace of economic development has sharply increased in the country, and the transition to a market economy has begun. Under the influence of these processes, new sections of the population were formed - the industrial bourgeoisie and the proletariat. Peasant and landlord farms were increasingly involved in commodity-money relations.

The emergence of zemstvos, city self-government, democratic transformations in the judiciary and educational systems testified to the steady, although not so fast, movement of Russia towards the foundations of civil society and the rule of law.

However, almost all reforms were inconsistent and incomplete. They retained the estate advantages of the nobility and state control over society. On the national outskirts of the reforms were implemented in an incomplete manner. The principle of the autocratic power of the monarch remained unchanged.

Foreign policy The government of Alexander II was active in almost all main areas. Diplomatic and military Russian state managed to solve the foreign policy tasks facing him, to restore his position as a great power. At the expense of the Central Asian territories, the boundaries of the empire expanded.

The era of "great reforms" has become a time of transformation of social movements into a force capable of influencing power or resisting it. Fluctuations in the government's course and the inconsistency of the reforms led to an increase in radicalism in the country. The revolutionary organizations embarked on the path of terror, striving to raise the peasants to the revolution through the assassination of the tsar and high officials.

Peasant Reform .............................................. .1

Liberal Reforms of the 60s-70s.......................................4

Establishment of zemstvos............................................ .4

Self-government in cities........................................ 6

Judicial reform............................................ 7

Military reform............................................... .8

Education reforms............................... ....10

Church in the period of reforms................................................. 11 Conclusion .......... ....................................…........ .thirteen

Peasant reform .

Russia on the eve of the abolition of serfdom . The defeat in the Crimean War testified to the serious military-technical lag of Russia from the leading European states. There was a threat of the country sliding into the category of minor powers. The government could not allow this. Along with the defeat came the understanding that the main reason for Russia's economic backwardness was serfdom.

The enormous costs of the war seriously undermined the monetary system of the state. Recruitment, the seizure of livestock and fodder, the growth of duties ruined the population. And although the peasants did not respond to the hardships of the war with mass uprisings, they were in a state of intense expectation of the tsar's decision to abolish serfdom.

In April 1854, a decree was issued on the formation of a reserve rowing flotilla ("sea militia"). With the consent of the landowner and with a written obligation to return to the owner, serfs could also be recorded in it. The decree limited the flotilla formation area to four provinces. However, he stirred up almost all of peasant Russia. A rumor spread in the villages that the emperor was calling volunteers for military service and for this he freed them forever from serfdom. Unauthorized registration in the militia resulted in a mass exodus of peasants from the landowners. This phenomenon took on an even broader character in connection with the manifesto of January 29, 1855, on the recruitment of warriors into the land militia, covering dozens of provinces.

The atmosphere in the "enlightened" society has also changed. According to the figurative expression of the historian V. O. Klyuchevsky, Sevastopol hit stagnant minds. “Now the question of the emancipation of serfs is on everyone’s lips,” wrote the historian K. D. Kavelin, “they talk about it loudly, even those who previously could not hint at the fallibility of serfdom without causing nervous attacks think about it.” Even the tsar's relatives - his aunt, Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna, and younger brother Konstantin - advocated for the transformation.

Preparation of the peasant reform . For the first time, on March 30, 1856, Alexander II officially announced the need to abolish serfdom to representatives of the Moscow nobility. At the same time, knowing the mood of the majority of the landowners, he emphasized that it is much better if this happens from above than to wait until it happens from below.

On January 3, 1857, Alexander II formed a Secret Committee to discuss the issue of abolishing serfdom. However, many of its members, former Nicholas dignitaries, were ardent opponents of the liberation of the peasants. They hindered the work of the committee in every possible way. And then the emperor decided to take more effective measures. At the end of October 1857, Vilna Governor-General VN Nazimov arrived in St. Petersburg, who in his youth was Alexander's personal adjutant. He brought the appeal of the nobles of the Vilna, Kovno and Grodno provinces to the emperor. They asked permission to discuss the issue of freeing the peasants without giving them land. Alexander took advantage of this request and on November 20, 1857, sent Nazimov a rescript on the establishment of provincial committees from among the landlords to prepare draft peasant reforms. On December 5, 1857, St. Petersburg Governor-General P. I. Ignatiev received a similar document. Soon the text of the rescript sent to Nazimov appeared in the official press. Thus, the preparation of the peasant reform became public.

During 1858, "committees for improving the life of landlord peasants" were established in 46 provinces (officials were afraid to include the word "liberation" in official documents). In February 1858, the Secret Committee was renamed the Main Committee. Grand Duke Konstantin Nikolayevich became its chairman. In March 1859 Editorial Commissions were established under the Main Committee. Their members were engaged in the consideration of materials coming from the provinces, and drawing up on their basis a general draft law on the emancipation of the peasants. General Ya. I. Rostovtsev, who enjoyed the emperor's special confidence, was appointed chairman of the commissions. He attracted to his work supporters of reforms from among the liberal officials and landowners - N. A. Milyutin, Yu. F. Samarin, V. A. Cherkassky, Ya. ". They advocated the release of the peasants with a land allotment for redemption and their transformation into small landowners, while the landownership was preserved. These ideas were fundamentally different from those expressed by the nobles in the provincial committees. They believed that even if the peasants were to be liberated, then without land. In October 1860, the editorial commissions completed their work. The final preparation of the reform documents was transferred to the Main Committee, then they were approved by the State Council.

The main provisions of the peasant reform. On February 19, 1861, Alexander II signed a manifesto “On granting serfs the rights of the status of free rural inhabitants and on the organization of their life”, as well as the “Regulations on peasants who emerged from serfdom”. According to these documents, the peasants, who previously belonged to the landlords, were declared legally free and received general civil rights. When they were released, they were given land, but in a limited amount and for ransom on special conditions. The land allotment, which the landowner provided to the peasant, could not be higher than the norm established by law. Its size ranged from 3 to 12 acres in various parts of the empire. If by the time of liberation there was more land in peasant use, then the landowner had the right to cut off the surplus, while the lands of better quality were taken from the peasants. According to the reform, the peasants had to buy the land from the landowners. They could get it for free, but only a quarter of the allotment determined by law. Until the redemption of their land plots, the peasants found themselves in the position of temporarily liable. They had to pay dues or serve corvee in favor of the landowners.

The size of allotments, dues and corvées were to be determined by an agreement between the landowner and the peasants - Charters. The temporary state could last for 9 years. At this time, the peasant could not give up his allotment.

The amount of the ransom was determined in such a way that the landowner would not lose the money that he had previously received in the form of dues. The peasant had to immediately pay him 20-25% of the value of the allotment. To enable the landowner to receive the redemption sum at a time, the government paid him the remaining 75-80%. The peasant, on the other hand, had to repay this debt to the state for 49 years with an accrual of 6% per annum. At the same time, calculations were made not with each individual, but with the peasant community. Thus, the land was not the personal property of the peasant, but the property of the community.

Peace mediators, as well as provincial presences for peasant affairs, consisting of the governor, government official, prosecutor and representatives of local landowners, were supposed to monitor the implementation of the reform on the ground.

The reform of 1861 abolished serfdom. The peasants became free people. However, the reform preserved serfdom remnants in the countryside, primarily landownership. In addition, the peasants did not receive full ownership of the land, which means they did not have the opportunity to rebuild their economy on a capitalist basis.

Liberal reforms of the 60-70s

Establishment of zemstvos . After the abolition of serfdom, a number of other transformations were required. By the beginning of the 60s. the former local administration showed its complete failure. The activities of the officials appointed in the capital who led the provinces and districts, and the detachment of the population from making any decisions, brought economic life, health care, and education to extreme disorder. The abolition of serfdom made it possible to involve all segments of the population in solving local problems. At the same time, when establishing new governing bodies, the government could not ignore the moods of the nobles, many of whom were dissatisfied with the abolition of serfdom.