Biography of Zheng He. Treasury of Admiral Zheng He

Send your good work in the knowledge base is simple. Use the form below

Students, graduate students, young scientists who use the knowledge base in their studies and work will be very grateful to you.

Posted on http://www.allbest.ru/

Posted on http://www.allbest.ru/

Message on the topic: Zheng He and his 7 journeys

Prepared by a student of the DTT-1 group, Denisenko Anastasia

Zheng He(1371--1435) - Chinese traveler, naval commander and diplomat, who led seven large-scale naval military-trade expeditions sent by the emperors of the Ming dynasty to the countries of Indochina, Hindustan, the Arabian Peninsula and East Africa.

At birth, the future navigator received the name Ma He. He was born in Hedai Village, Kunyang County. The Ma family came from the so-called sam- people from Central Asia who arrived in China during the Mongol rule and held various positions in the state apparatus of the Yuan Empire. Majority sam, including the ancestors of Zheng He, were Muslims (it is often believed that the surname "Ma" itself is nothing more than the Chinese pronunciation of the name "Muhammad"). traveler chinese expedition military

Not much is known about Ma He's parents. The father of the future navigator was known as Ma Haji (1345-1381 or 1382), in honor of his pilgrimage to Mecca; his wife's surname was Wen. There were six children in the family: four daughters and two sons - the eldest, Ma Wenming, and the youngest, Ma He.

Entering the service of Zhu Di and military career

After the overthrow Mongolian yoke in central and northern China and the establishment of the Ming Dynasty by Zhu Yuanzhang (1368), the mountainous province of Yunnan on the southwestern outskirts of China remained under the control of the Mongols for several more years. It is not known whether Ma Haji fought on the side of the Yuan loyalists during the conquest of Yunnan by the Ming troops, but be that as it may, he died during this campaign (1382), and his youngest son Ma He was captured and fell into the service of Zhu Di , the son of Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang, who led the Yunnan campaign.

Three years later, in 1385, the boy was castrated, and he became one of the many eunuchs at the court of Zhu Di. The young eunuch got a name Ma Sanbao i.e. Ma "Three Treasures" or "Three Jewels". According to Needham, despite the eunuch's undeniably Muslim origin, this title of his served as a reminder of the "three jewels" of Buddhism (Buddha, Dharma and Sangha), whose names are so often repeated by Buddhists.

The first Ming emperor Zhu Yuanzhang planned to transfer the throne to his firstborn son Zhu Biao, but he died during the life of Zhu Yuanzhang. As a result, the first emperor appointed Zhu Biao's son, Zhu Yunwen, as his heir, although his uncle Zhu Di (one of Zhu Yuanzhang's younger sons) certainly considered himself more worthy of the throne. Having ascended the throne in 1398, Zhu Yunwen, who was afraid of the seizure of power by one of his uncles, began to destroy them one by one. Soon a civil war broke out between the young emperor in Nanjing and his Beijing uncle Zhu Di.. Due to the fact that Zhu Yunwen forbade eunuchs to take part in the government of the country, many of them supported Zhu Di during the uprising. As a reward for their service, Zhu Di, for his part, allowed them to participate in solving political issues, and allowed them to rise to the highest levels. political career, which was also very beneficial for Ma Sanbao. The young eunuch distinguished himself both in the defense of Beiping in 1399 and in the capture of Nanjing in 1402, and was one of the commanders tasked with capturing the capital of the empire, Nanjing. Having destroyed the regime of his nephew, Zhu Di ascended the throne on July 17, 1402 under the motto of Yongle's reign.

On the (Chinese) new year of 1404, the new emperor granted Ma He the new surname Zheng as a reward for his faithful service. This served as a reminder of how, in the early days of the uprising, Ma He's horse was killed in the vicinity of Beiping in a place called Zhenglunba.

As for the appearance of the future admiral, he, “becoming an adult, they say, grew to seven chi (almost two meters. - Ed.), And the girth of his belt was equal to five chi (more than 140 centimeters. - Ed.). His cheekbones and forehead were wide, and his nose was small. He had a sparkling eye and a voice as loud as the sound of a great gong.

After Zheng He was awarded the title of "chief eunuch" for all his services to the emperor ( taijiang), which corresponded to the fourth rank of an official, Emperor Zhu Di decided that he was better than the rest for the role of admiral of the fleet and appointed a eunuch as the head of all or almost all of the seven voyages to Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean in 1405-1433, simultaneously raising him status up to the third rank.

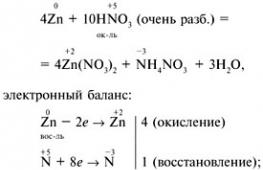

Baochuan: length - 134 meters, width - 55 meters, displacement - about 30,000 tons, crew - about 1,000 people

1. Cabin of Admiral Zheng He

2. Ship altar. The priests constantly burned incense on it - so they appeased the gods

3. Hold. Zheng He's ships were full of porcelain, jewelry, and other gifts for foreign rulers and a display of the emperor's might.

4. The rudder of the ship was equal in height to a four-story house. To bring it into action, a complex system of blocks and levers was used.

5. Observation deck. Standing on it, the navigators followed the pattern of the constellations, checked the course and measured the speed of the ship.

6. Waterline. The displacement of the baochuan is many times greater than that of contemporary European ships

7. The sails woven from bamboo mats opened like a fan and provided a high windage of the vessel

"Santa Maria" Columbus: length - 25 meters, width - about 9 meters, displacement - 100 tons, crew - 40 people.

The fleet apparently consisted of about 250 ships, and carried about 27,000 personnel on board, led by 70 imperial eunuchs. The flotilla led by Zheng He visited over 56 countries and major cities Southeast Asia and the Indian Ocean basin. Chinese ships reached the coast of Arabia and East Africa.

First expedition

Cheng-zu's first decree on equipping the expedition was issued in March 1405. By this decree, Zheng He was appointed its head, and the eunuch Wang Jihong was his assistant. The preparations for the expedition, apparently, had already begun earlier, since preparations were completed by the autumn of that year. The flotilla included sixty-two ships, on which there were twenty-seven thousand eight hundred people. However, in the Middle Ages in China, each big ship was accompanied by two or three more small, auxiliary. Gong Zhen, for example, speaks of auxiliary vessels that carried fresh water and food. There is evidence that their number reached one hundred and ninety units.

The ships were built at the mouth of the Yangtze, as well as on the shores of Zhejiang, Fujian and Guangdong, and then pulled to the anchorages on Liujiahe, where the flotilla was assembled. Leaving Lujiajiang, the fleet sailed along the coast of China to Taiping Bay in Changle County, Fujian Province. From the coast of Fujian, Zhang He's fleet set off for Champa. Passing through the South China Sea and rounding about. Kalimantan from the west, he approached the east coast of about. Java. From here, the expedition headed along the northern coast of Java to Palembang. Further, the path of the Chinese ships lay through the Strait of Malacca to the northwestern coast of Sumatra to the country of Samudra. Having entered the Indian Ocean, the Chinese fleet crossed the Bay of Bengal and reached the island of Ceylon. Then, rounding the southern tip of Hindustan, Zheng He visited several rich shopping centers on the Malabar coast, including the largest of the bottom - the city of Calicut. A rather colorful illustration of the Calicut market is given by G. Hart in his book “Sea Route to India”: “Chinese silk, thin cotton fabric of local production, famous throughout the East and Europe, calico fabric, cloves, nutmegs, their dried India and Africa, cinnamon from Ceylon, pepper from the Malabar coast, Sunda and Borneo, medicinal plants, ivory from the interior of India and Africa, bundles of cassia, sacks of cardamom, heaps of copra, coir rope, piles of sandalwood, yellow and mahogany." The wealth of this city makes it clear why Zhu Di sent the first expedition there.

In addition, on the first voyage on the way back, the Chinese expeditionary forces captured the famous pirate Chen Zui, who at that time captured Palembang, the capital of the Hindu-Buddhist state of Srivijaya in Sumatra. "Zheng He returned and brought Chen Zu" and in shackles. Arriving at the Old Port (Palembang), he called on Chen to submit. into battle, and Zheng He sent troops and took the fight.Chen was utterly defeated.More than five thousand bandits were killed, ten ships burned and seven captured...Chen and two others were captured and taken to the imperial capital, where they were ordered decapitate.” So the envoy of the metropolis protected the peaceful migrant compatriots in Palembang and at the same time demonstrated that his ships carried weapons on board not only for beauty.

Second expedition

Immediately after returning from a campaign in the fall of 1407, Zhu Di, surprised by the outlandish goods brought by the expedition, again sent Zheng He's fleet on a long voyage, but this time the flotilla consisted of only 249 ships, since a large number of ships in the first expedition turned out to be useless. The route of the second expedition (1407-1409) basically coincided with the route of the previous one, Zheng He visited mostly familiar places, but this time he spent more time in Siam (Thailand) and Calicut.

The Chinese expeditions returned home by the same route as before, and only incidents along the way make it possible to distinguish in the chronicles the voyages “there” from the return ones. During the second voyage, geographically similar to the first, only one event occurred, the memory of which has been preserved in history: the ruler of Calicut provided the envoys of the Celestial Empire with several bases, relying on which, the Chinese could continue to go even further to the west.

Third expedition

But the third expedition brought more interesting adventures. Under the date July 6, 1411, the chronicle records:

“Zheng He... returned and brought the captured king of Ceylon Alagakkonara, his family and freeloaders. During the first trip, Alagakkonara was rude and disrespectful and set out to kill Zheng He. Zheng He understood this and left. Moreover, Alagakkonara was not friends with neighboring countries and often intercepted and robbed their embassies on the way to China and back. In view of the fact that other barbarians suffered from this, Zheng He, on his return, again showed contempt for Ceylon. Then Alagakkonara lured Zheng He deep into the country and sent his son Nayanara to demand gold, silver and other precious goods from him. If these goods had not been given out, more than 50,000 barbarians would have risen from their hiding places and captured Zheng He's ships. They also sawed down trees and intended to block the narrow paths and cut off Zheng He's retreat so that separate Chinese detachments could not come to each other's aid.

When Zheng He realized that they were cut off from the fleet, he quickly deployed troops and sent them to the ships ... And he ordered the messengers to secretly bypass the roads where the ambush was sitting, return to the ships and convey the order to the officers and soldiers to fight to the death. In the meantime, he personally led the 2,000-strong army by detours. They stormed the eastern walls of the capital, took it with a fright, broke through inside, captured Alagakkonara, his family, freeloaders and dignitaries. Zheng He fought several battles and utterly defeated the barbarian army. When he returned, the ministers decided that Alagakkonar and the other captives should be executed. But the emperor took pity on them - on ignorant people who did not know what the Heavenly mandate to rule was, and let them go, giving them food and clothes, and ordered the Chamber of Rituals to choose a worthy person in the Alagakkonara family to rule the country.

It is believed that this was the only case when Zheng He consciously and decisively turned away from the path of diplomacy and entered into a war not with robbers, but with the official authorities of the country in which he arrived. The above quote is the only documentary description of the actions of the naval commander in Ceylon. However, besides him, of course, there are many legends. The most popular of them describes the scandal associated with the most revered relic - the tooth of the Buddha (Dalada), which Zheng He was either going to steal or really stole from Ceylon.

The story is this: back in 1284, Khubilai sent his emissaries to Ceylon in order to get one of the main sacred relics of Buddhists in a completely legal way. But the Mongol emperor - the famous patron of Buddhism - was still not given a tooth, compensating for the refusal with other expensive gifts. This ended the matter for the time being. But according to the Sinhalese myths, the Middle State secretly did not abandon the desired goal. They generally claim that the admiral's voyages were undertaken almost specifically for the theft of a tooth, and all other wanderings were for averting eyes. But the Sinhalese allegedly outwitted Zheng He - they "slipped" him a royal double instead of the real king and a false relic, and hid the real one while the Chinese were fighting. Compatriots of the great navigator, of course, hold the opposite opinion: the admiral nevertheless got the priceless "piece of Buddha", and even in the manner of a guiding star, he helped him safely get back to Nanjing. What actually happened is unknown.

Fourth expedition

In mid-December 1412, Zheng He received a new order to bring gifts to the courts of overseas rulers. The main event of this campaign was the capture of a certain leader of the rebels named Sekandar. He had the misfortune to speak out against the king of the state of Semudera in the north of Sumatra, Zain al-Abidin, recognized by the Chinese and connected with them by a treaty of friendship. The arrogant rebel was offended that the emperor's envoy did not bring him gifts, which means that he did not recognize him as a legitimate representative of the nobility, hastily gathered supporters and attacked the admiral's fleet himself. True, he had no more chances of winning than a pirate from Palembang. Soon he, his wives and children were on board the Chinese treasures. Ma Huan reports that the "robber" was publicly executed back in Sumatra, without being honored by the imperial court in Nanjing. But the naval commander brought to the capital from this voyage a record number of foreign ambassadors - from thirty powers. Eighteen of them were taken home by Zheng He during the fifth expedition. All of them had with them gracious letters from the emperor, as well as porcelain and silk - embroidered, transparent, dyed, thin and very expensive, so that their sovereigns, presumably, were satisfied. And the admiral himself, this time, set off into uncharted waters, to the shores of Africa.

Fifth expedition

During the next (1417-1419) they visited Lasa (a point near the modern city of Mersa Fatima in the Red Sea) and a number of cities on the Somali coast of Africa - Mogadishu, Brava, Chzhubu and Malindi. The fleet rounded the Horn of Africa and really went to Mogadishu, where the Chinese met with a real miracle: they saw how, for lack of wood, the black people were building stone houses - four or five floors. Rich people engaged in maritime trade, poor people cast nets in the ocean. Small cattle, horses and camels were fed with dried fish. But the main thing is that the travelers brought home a very special “tribute”: leopards, zebras, lions and even a few giraffes. Unfortunately, the African gifts did not satisfy the emperor at all. In fact, the goods and offerings from the already familiar Calicut and Sumatra were of much greater material value than the exotic new settlers of the imperial menagerie.

Sixth expedition

During the sixth voyage (1421-1422), Zheng He's fleet again reached the coast of Africa. When, in the spring of 1421, having reinforced the fleet with 41 ships, the admiral again sailed to the Black Continent and returned again without any convincing values, the emperor was completely annoyed. In addition, in the Celestial Empire itself, criticism of his devastating wars intensified during this time. In general, the further campaigns of the great flotilla turned out to be a big question.

Seventh expedition

Be that as it may, contrary to Menzies' assertion, Zheng He's sixth voyage was not the last expedition of the Chinese admiral. Like the previous voyages, the seventh expedition of Zheng He (1431-1433) and the expedition of his closest assistant Wang Jianghong that followed it were crowned with success. The embassy relations of the countries of the South Seas with China revived again, and the rulers of these countries arrived at the imperial court from Malacca (1433) and Samudra (1434). By this time, at the court of the emperor, the group of close associates of Zhu Di was growing stronger, who insisted on reducing the expeditions and returning to the policy of isolationism. After the death of Zhu Di, under the influence of such court moods, the new emperor insisted on stopping the expeditions, as well as destroying all evidence of their conduct. It is especially surprising that no one knows for certain when the famous admiral Zheng He died - either during the seventh voyage, or shortly after the return of the fleet (July 22, 1433). In modern China, it is generally accepted that he, as a real sailor, was buried in the ocean, and the cenotaph, which is shown to tourists in Nanjing, is only a conditional tribute to memory.

Meaning

Zheng He's expeditions contributed to the cultural exchange of African and Asian countries with China and the establishment of trade relations between them. Detailed descriptions of the countries and cities visited by Chinese navigators were compiled. Their authors were members of Zheng He's expedition - Ma Huan, Fei Xin (en: Fei Xin) and Gong Zheng (en: Gong Zhen). Detailed "Charts of Zheng He's voyages" were also compiled. On the basis of materials and information collected by members of Zheng He's sea expeditions, in Ming China in 1597, Lo Mao-teng wrote the novel Zheng He's Voyages to the Western Ocean. As the Russian sinologist A.V. Velgus pointed out, there is a lot of fantasy in it, however, in some descriptions, the author definitely used data from historical and geographical sources.

heirs

Having been a eunuch since childhood, Zheng He had no children of his own. However, he adopted one of his nephews, Zheng Haozhao, who, unable to inherit his adoptive father's titles, was nevertheless able to retain his property. Therefore, to this day, there are people who consider themselves "descendants of Zheng He."

It is pleasant to note that in 1997 the magazine life in the list of 100 people who have had the greatest impact on history in the last millennium, he placed Zheng He in 14th place.

Hosted on Allbest.ru

...Similar Documents

Biography of Francisco Franco Baamonde. War between Spain and the United States of America (1898). Franco's military career, hostility between the military of the mother country and the "Africanists". Operation value under AluseMase. A successful marriage is a ticket to high society.

term paper, added 08/10/2009

Biography of Christopher Columbus - a Spanish navigator of Italian origin, who in 1492 discovered America for Europeans, thanks to the equipment of expeditions by the Catholic kings. Chronology of travels in 1492-1504. Mass colonization of Hispaniola.

presentation, added 03/15/2015

Biography of Tamerlane (1336–1405) - an outstanding Central Asian statesman, commander and ruler of Maverannahr, analysis of his place in history. General characteristics of the period of wars among the Timurids. Description of the history of the collapse of the Timurid Empire.

term paper, added 12/21/2010

Biography of Issa Pliev - Army General, twice Hero of the Soviet Union. Difficult childhood, the formation of the character of the future commander, military career. Conducting an operation to defeat the Kwantung Army. post-war service. Awards and titles. The memory of him.

presentation, added 12/05/2011

Basic concepts of travel and geographical discoveries made in Ancient Rome. The main reasons and motivations for travel. Features of travel in ancient Rome. The connection between ancient Roman traditions and how they influenced modern tourism.

term paper, added 06/08/2014

The international position of Russia and its military potential in the First World War. Long road to the glory of A.A. Brusilov - biography and glorious military career. The commander's finest hour - the famous Brusilovsky breakthrough in the summer of 1916. Supreme Commander.

abstract, added 01/30/2008

Biography of Twice Hero of the Soviet Union, Marshal Rodion Yakovlevich Malinovsky. Early years of life, military career, participation in the First World War and civil wars, in the Great Patriotic War. Activities of Malinovsky as Minister of Defense.

presentation, added 01/16/2013

Acquaintance with the personality of Emperor Alexander II, his brief biography. Bourgeois reforms of the 60-70s of the XIX century, carried out in Russia. The historical significance of the abolition of serfdom, the significance of the peasant reform. Zemstvo, judicial and military reforms.

term paper, added 07/13/2012

Biography and military career of Davydov Denis Vasilyevich. Start Patriotic War. Battle of Borodino and its significance for Russia. People's militia and its role. Napoleon's army crossing the Neman. The occupation of Moscow and the retreat of Napoleon's army.

presentation, added 02/09/2012

Personality and diplomatic career of A.M. Gorchakova: biography, political activity. Main merits: The London Convention of 1871, the Berlin Congress of 1878. Evaluation of the foreign policy principles of a diplomat: the views of Russian and foreign scientists.

The Chinese empire, throughout its centuries-old history, did not particularly show interest in distant countries and travel. However, in the XV century, the Chinese fleet went on long-distance expeditions seven times in a row and all seven times it was led by the great Chinese admiral Zheng He ...

In 2002, a book was published by a retired British officer, former commander submarine Gavin Menzies, 1421: The Year China Discovered the World. In it, Menzies assured that Zheng He was even ahead of Columbus, having discovered America before him, he allegedly outstripped Magellan, being the first to circumnavigate the globe.

Professional historians dismiss these theories as untenable. And yet, one of the admiral's maps - the so-called "Kan" nido map - confirms that Zheng He had reliable and reliable information about Europe ...

There is also a point of view that Zheng He's maps served as the basis for European nautical charts from the era of the Great Geographical Discoveries.

Zheng He was born in 1371 in the city of Kunyang (now Jinying), in the center of the southwestern Chinese province of Yunnan, near its capital Kunming. It was a few weeks' drive from Kunyang to the coast - a huge distance at that time - so Ma He, as he was called in childhood, did not even imagine that he would become a great naval commander and traveler.

The He clan descended from the famous Said Ajalla Shamsa al-Din (1211-1279), who was also called Umar, a native of Bukhara, who was able to rise during the time of the Mongol great khans Mongke (grandson of Genghis Khan) and Khubilai.

Actually, the conqueror of China great khan Kublai in 1274 and installed Umar as governor of Yunnan.

It is also known for certain that the father and grandfather of the future admiral Zheng He strictly observed the code of Islam and made a hajj to Mecca. In addition, there is an opinion in the Muslim world that the future admiral himself visited the holy city, although in fairness it should be noted that with an informal pilgrimage.

Ma He's childhood was very dramatic.

In 1381, during the conquest of Yunnan by the troops of the Chinese Ming Dynasty, which overthrew the foreign Yuan, his father died at the age of 39, and Ma He was captured by the rebels, castrated and given into the service of the fourth son of their leader Hong-wu, the future Emperor Yongle, who soon went to the governor of Beiping (Beijing).

Eunuchs in China have always been one of the most influential political forces. Some teenagers themselves went on a terrible operation, hoping to get into the retinue of some influential person - the prince or, if fortune smiles, the emperor himself. So the “color-eyed” (as the representatives of the non-titular, non-Han people were called in China) Zheng He, according to the ideas of that time, was simply unrealistically lucky ...

Ma He proved himself in the service on the positive side and by the end of the 1380s he became noticeable in the environment of the prince, whose junior he was eleven years.

When in 1399 Beijing was besieged by the troops of the then Emperor Jianwen, who ruled from 1398 to 1402, the young dignitary courageously defended one of the city's reservoirs, which allowed the prince to stand in order to counterattack his rival and ascend the throne.

A few years later, Yongle gathered a strong militia, raised an uprising, and in 1402, having taken the capital Nanjing by storm, he proclaimed himself emperor.

At the same time, he adopted the new reign's motto: Yongle - "Eternal Happiness".

Ma He was also generously rewarded: on the Chinese New Year - in February 1404 - in gratitude for his loyalty and exploits, he was solemnly renamed Zheng He - this surname corresponds to the name of one of the ancient kingdoms that existed in China in the 5th-3rd centuries BC e.

Zheng He's first expedition took place in 1405. Initially, the Yongle Emperor himself, who lived in Nanjing, where they built ships and where the first trips started, took a direct part in the project. Later, the arrangement of the new capital in Beijing and the Mongol campaigns will cool the emperor's ardor, but for now he personally meticulously delves into all the little things, closely follows every step and instructions of his admiral.

In addition, the Yongle Emperor placed a trusted eunuch at the head of not only the flotilla itself, but also the Chamber of Palace Servants. And this means that he also had to be responsible for the construction and repair of many buildings, and then the construction of ships ...

But the emperor hurried with the construction of ships and special orders to the province of Fujian and the tops of the Yangtze sent parties for wood for their construction. The beauty and pride of the squadron, baochuan, which literally sounds like “precious ships” or “treasuries”, was built at the “precious ships shipyard” (baochuanchang) on the Qinhuai River in Nanjing. Therefore, despite their gigantic size, the draft of the junks was not very deep - otherwise they would not have entered the sea through this tributary of the Yangtze.  Baochuan was 134 meters long and 55 meters wide.

Baochuan was 134 meters long and 55 meters wide.

Draft to the waterline was more than 6 meters.

There were 9 masts, and they carried 12 sails made of woven bamboo mats. 2

On July 11, 1405, the following entry was made in the Chronicle of Emperor Taizong (one of the ritual names of Emperor Yongle):

“Palace dignitary Zheng He and others were sent to the countries of the Western (Indian) Ocean with letters from the emperor and gifts for their kings - golden brocade, patterned silks, colored silk gauze, all according to their status.”

The armada of the first expedition of Admiral Zheng He included 255 ships with 27,800 people on board. The ships followed the following route: East coast of Indochina (Champa state), Java (ports north coast), Malacca Peninsula (Sultanate of Malacca), Sumatra (sultanates of Samudra-Pasai, Lamuri, Haru, Palembang), Ceylon, Malabar coast of India (Calicut) 1 .

In all his expeditions, Zheng He went the same way each time: catching the recurring monsoon winds that blow from December to March at these latitudes from the north and northeast.

And when the humid subequatorial air currents rose over the Indian Ocean and, as it were, turned back to the north in a circle - from April to August, the flotilla turned to the house. This monsoon schedule was known to local sailors long before our era, and not only to sailors: after all, it also determined the order of agricultural seasons.

Taking into account the monsoons, as well as the pattern of constellations, travelers confidently crossed from the south of Arabia to the Malabar coast of India, or from Ceylon to Sumatra and Malacca, adhering to a certain latitude.

The Chinese expeditions returned home by the same route, and only incidents that happened on the way make it possible to distinguish between voyages “there” and “back” in the chronicles.

On the first expedition on the way back, the Chinese captured the famous pirate Chen Zu, who at that time captured Palembang, the capital of the Hindu-Buddhist state of Srivijaya in Sumatra.

"Zheng He returned and brought Chen Zu" and in shackles. Arriving at the Old Port, he urged Chen to obey.

He pretended to obey, but secretly planned a riot. Zheng He understood this...

Chen, having gathered his forces, went into battle, and Zheng He sent troops and accepted the battle.

Chen was utterly defeated. More than five thousand bandits were killed, ten ships were burned and seven were captured...

Chen and two others were taken prisoner and taken to the imperial capital, where they were ordered to be beheaded."

So Zheng He protected the peaceful fellow migrants in Palembang and along the way for the first time showed that his ships had weapons on board not only for beauty.

Until today, researchers have not agreed on what exactly the admiral's subordinates fought with. The fact that Chen Zu's ships were burned seems to indicate that they were shot from cannons. They, like primitive guns, were already used then in China, but there is no direct evidence of their use at sea.

In battle, Admiral Zheng He relied on manpower, on personnel that were landed from huge junks ashore or sent to storm the fortifications. This peculiar marine corps was the main force of the flotilla.

During the second expedition, which took place in 1407-1409, geographically similar to the first (East coast of Indochina (Champa, Siam), Java (ports of the northern coast), Malacca Peninsula (Malacca), Sumatra (Samudra-Pasai, Palembang), Malabar coast India (Cochin, Calicut)) 1, only one event occurred, the memory of which has been preserved in history: the ruler of Calicut provided the envoys of the Celestial Empire with several bases, relying on which the Chinese could go even further to the west.

But during the third expedition, which took place in 1409-1411. (East coast of Indochina (Champa, Siam), Java (north coast ports), Malacca Peninsula (Malacca), Singapore, Sumatra (Samudra Pasai), Malabar coast of India (Kollam, Cochin, Calicut)) 1 , more serious events occurred.

Under the date July 6, 1411, the chronicle records:

“Zheng He... returned and brought the captured king of Ceylon Alagakkonara, his family and freeloaders.

During the first trip, Alagakkonara was rude and disrespectful and set out to kill Zheng He. Zheng He understood this and left.

Moreover, Alagakkonara was not friends with neighboring countries and often intercepted and robbed their embassies on the way to China and back. In view of the fact that other barbarians suffered from this, Zheng He, on his return, again showed contempt for Ceylon.

Then Alagakkonara lured Zheng He deep into the country and sent his son Nayanara to demand gold, silver and other precious goods from him. If these goods had not been given out, more than 50,000 barbarians would have risen from their hiding places and captured Zheng He's ships.

They also sawed down trees and intended to block the narrow paths and cut off Zheng He's retreat so that separate Chinese detachments could not come to each other's aid.

When Zheng He realized that they were cut off from the fleet, he quickly deployed his troops and sent them to the ships...

And he ordered the messengers to secretly bypass the roads where the ambush sat, return to the ships and convey the order to the officers and soldiers to fight to the death.

In the meantime, he personally led the 2,000-strong army by detours. They stormed the eastern walls of the capital, took it with a fright, broke through inside, captured Alagakkonara, his family, freeloaders and dignitaries.

Zheng He fought several battles and utterly defeated the barbarian army.

When he returned, the ministers decided that Alagakkonar and the other captives should be executed. But the emperor took pity on them - on ignorant people who did not know what the Heavenly mandate to rule was, and let them go, giving them food and clothes, and ordered the Chamber of Rituals to choose a worthy person in the Alagakkonara family to rule the country.

This quote is the only documentary depiction of Zheng He's deeds in Ceylon. But nevertheless, besides him, of course, there are many legends, and the most famous of them tells about the scandal that is associated with the most respected relic - the tooth of the Buddha (Dalada), which Zheng He either intended to steal or actually stole from Ceylon.

And this story is...

In 1284, Khan Kublai sent his emissaries to Ceylon to get one of the paramount sacred relics of the Buddhists in a completely legal way. But the tooth of the Mongol emperor - the famous patron of Buddhism - was still not given away, compensating for the refusal with other expensive gifts.

According to the Sinhalese myths, the Middle State secretly did not retreat from the desired goal. These myths claim that the expeditions of Admiral Zheng He were undertaken almost with the intention of stealing a tooth, and all other campaigns were for averting eyes.

The Sinhalese, on the other hand, allegedly outwitted Zheng He - they "slipped" him into captivity the royal double instead of the true king and a false relic, and hid the real one, while the Chinese fought.

The compatriots of the great admiral, of course, are of the opposite opinion: Admiral Zheng He nevertheless received an invaluable “piece of Buddha”, and even in the manner of a guiding star, he helped him safely return back to Nanjing.

But what really happened is unknown ...

Admiral Zheng He was a very broad-minded person. A Muslim by birth, he discovered Buddhism already in adulthood and was distinguished by great knowledge in the intricacies of this teaching.

In Ceylon, he erected a sanctuary of Buddha, Allah and Vishnu (one for three!), And in a stele erected before the last voyage to Fujian, he thanked the Taoist goddess Tian-fei, the “divine wife”, who was revered as the patroness of sailors.

To some extent, the Ceylon adventures of the admiral, most likely, became the pinnacle of his overseas career. During this dangerous military campaign, many soldiers died, but Yongle, appreciating the scale of the feat, generously rewarded the survivors.

In mid-December 1412, Zheng He received a new order from the emperor to bring gifts to the courts of overseas rulers. This fourth expedition of Zheng He, which took place in 1413-1415,  passed along the route: East coast of Indochina (Champa), Java (ports of the northern coast), Malacca Peninsula (sultanates of Pahang, Kelantan, Malacca), Sumatra (Samudra Pasai), Malabar coast of India (Cochin, Calicut), Maldives, coast of the Persian Gulf (State of Hormuz). one

passed along the route: East coast of Indochina (Champa), Java (ports of the northern coast), Malacca Peninsula (sultanates of Pahang, Kelantan, Malacca), Sumatra (Samudra Pasai), Malabar coast of India (Cochin, Calicut), Maldives, coast of the Persian Gulf (State of Hormuz). one

A Muslim translator, Ma Huan, who knew Arabic and Persian, was assigned to the fourth expedition.

Later, in his memoirs, he will describe the last great voyages of the Chinese fleet, as well as all sorts of everyday details.

In particular, Ma Huan scrupulously described the diet of the sailors: they ate “husked and unhusked rice, beans, grains, barley, wheat, sesame and all kinds of vegetables ... From fruits they had ... Persian dates, pine nuts, almonds, raisins, walnuts, apples, pomegranates, peaches and apricots...”, “many people made a mixture of milk, cream, butter, sugar and honey and ate it”.

It is safe to conclude that the Chinese travelers did not suffer from scurvy.

The key event of the fourth expedition of Zheng He was the capture of the leader of the rebels named Sekandar, who opposed the king of the state of Semuder in northern Sumatra, Zain al-Abidin, recognized by the Chinese and associated with them by a friendship treaty.

Sekandar was offended that the emperor's envoy did not bring him gifts, which means that he did not recognize him as a legitimate representative of the nobility, hastily gathered supporters and himself attacked the fleet of Admiral Zheng He.

But soon he himself, his wives and children got on board the Chinese treasuries. In his notes, Ma Huan writes that the "robber" was publicly executed back in Sumatra, without being honored by the imperial court in Nanjing...

From this expedition, Admiral Zheng He brought a record number of foreign ambassadors - from thirty powers. Eighteen diplomats of them Zheng He took home during the fifth expedition, which took place in 1416-1419.

All of them carried gracious letters from the emperor, as well as porcelain and silk - embroidered, transparent, dyed, thin and very expensive, so that their sovereigns, presumably, were satisfied.

This time, Admiral Zheng He chose the next route of his expedition - the East coast of Indochina (Champa), Java (ports of the northern coast), the Malacca Peninsula (Pahang, Malacca), Sumatra (Samudra Pasai), the Malabar coast of India (Cochin, Calicut), Maldives, coast of the Persian Gulf (Ormuz), coast of the Arabian Peninsula (Dhofar, Aden), east coast of Africa (Barawa, Malindi, Mogadishu) 1 .

The fleet of this expedition included 63 ships and 27,411 people.

There are many inaccuracies and discrepancies in the descriptions of the fifth expedition of Admiral Zheng He. It is still unknown where the mysterious fortified Lasa is located, which offered armed resistance to Zheng He's expeditionary force and was taken by the Chinese with the help of siege weapons, which in some sources are called "Muslim catapults", in others - "Western" and, in the end, in third - "huge catapults shooting stones" ...

Some sources indicate that this city was in Africa, near Mogadishu in modern Somalia,  others are in Arabia, somewhere in Yemen. The way to it from Calicut took twenty days in the 15th century with a fair wind, the climate there was sultry, the fields were scorched, the traditions were simple, and there was almost nothing to take there.

others are in Arabia, somewhere in Yemen. The way to it from Calicut took twenty days in the 15th century with a fair wind, the climate there was sultry, the fields were scorched, the traditions were simple, and there was almost nothing to take there.

Frankincense, ambergris and "thousand li camels" (li is a Chinese measure of length, approximately 500 meters).

The fleet of Admiral Zheng He rounded the Horn of Africa and headed for Mogadishu, where the Chinese encountered a real miracle: they saw how, due to the lack of wood, the black people build houses of stones - four to five floors.

The rich inhabitants of those places were engaged in maritime trade, the poor threw nets in the ocean.

Small cattle, horses and camels were fed with dried fish. But the main thing is that the Chinese brought home a very peculiar “tribute”: leopards, zebras, lions and even a few giraffes, with which, by the way, the Chinese emperor was completely dissatisfied ...

The sixth expedition of Zheng He took place in 1421-1422 and took place along the route - the East coast of Indochina (Champa), Java (ports of the northern coast), the Malay Peninsula (Pahang, Malacca), Sumatra (Samudra Pasai), the Malabar coast of India (Cochin, Calicut), Maldives, coast of the Persian Gulf (Ormuz), coast of the Arabian Peninsula 1 . The fleet was reinforced with 41 ships.

From this expedition, Zheng He again returned without any valuables, which completely annoyed the emperor. In addition, in the Celestial Empire itself, criticism of his devastating wars intensified during this time, and therefore the further campaigns of Zheng He's great flotilla turned out to be a big question...

In 1422-1424, Zheng He's voyages took a significant break, and in 1424, the Yongle Emperor died.

And only in 1430, the new, young emperor Xuande, the grandson of the late Yongle, decided to send another "great embassy".  The last, seventh expedition of Admiral Zheng He took place in 1430-1433 along the route - the East coast of Indochina (Champa), Java (Surabaya and other ports of the northern coast), the Malay Peninsula (Malacca), Sumatra (Samudra-Pasai, Palembang) , the Ganges delta region, the Malabar coast of India (Kollam, Calicut), the Maldives, the coast of the Persian Gulf (Ormuz), the coast of the Arabian Peninsula (Aden, Jeddah), the east coast of Africa (Mogadishu). 27,550 people took part in this expedition.

The last, seventh expedition of Admiral Zheng He took place in 1430-1433 along the route - the East coast of Indochina (Champa), Java (Surabaya and other ports of the northern coast), the Malay Peninsula (Malacca), Sumatra (Samudra-Pasai, Palembang) , the Ganges delta region, the Malabar coast of India (Kollam, Calicut), the Maldives, the coast of the Persian Gulf (Ormuz), the coast of the Arabian Peninsula (Aden, Jeddah), the east coast of Africa (Mogadishu). 27,550 people took part in this expedition.

Admiral Zheng He, who was in his seventies by the time of his departure, ordered two inscriptions to be carved in the port of Liujiagang (near the city of Taicang in Jiangsu province) and in Changle (eastern Fujian) before sailing on the last expedition - a kind of epitaph in which he summed up the results of a large way.

During this expedition, the fleet landed a detachment under the command of Hong Bao, who made a peaceful sortie to Mecca. Sailors returned with giraffes, lions, "camel bird" (ostrich, giant birds were still found in Arabia at that time) and other wondrous gifts that were carried by ambassadors from the sheriff of the Holy City.

Five days after the completion of the seventh expedition, the emperor, according to tradition, presented the team with ceremonial robes and paper money. According to the chronicle, Xuande said:

“We have no desire to receive things from distant countries, but we understand that they were sent with the most sincere feelings. Since they have come from afar, they should be accepted, but this is not a reason for congratulations.

Diplomatic ties between China and the countries of the Western Ocean were interrupted this time - for centuries. Some merchants continued to trade with Japan and Vietnam, but the Chinese authorities abandoned the "state presence" in the Indian Ocean and even destroyed most of Zheng He's sailing boats.

Decommissioned ships rotted in the port, and Chinese shipbuilders forgot how to build baochuan...

No one knows for sure when the famous admiral Zheng He died - either during the seventh expedition, or shortly after the return of the fleet (July 22, 1433).

In modern China, it is believed that he, as a true sailor, was buried in the ocean, and the cenotaph, which is shown to tourists in Nanjing, is only a conditional tribute to memory.

What is most surprising is the fact that Zheng He's expeditions, which were so serious in scale, were completely forgotten by both contemporaries and descendants upon their completion. It was only at the beginning of the 20th century that Western scholars discovered references to these voyages in the chronicles of the imperial Ming dynasty and asked themselves the question: why was this huge flotilla created?

Various versions were put forward: either Zheng He turned out to be a “pioneer and explorer” like Cook, or he was looking for colonies for the empire like conquistadors, or his fleet was a powerful military cover for developing foreign trade, like the Portuguese had in the XV-XVI centuries.

The famous Russian sinologist Alexei Bokshchanin in the book "China and the countries of the South Seas"  gives an interesting consideration about the possible purpose of these expeditions: by the beginning of the 15th century, relations between China of the Ming era and the state of Tamerlane, who even planned a campaign against China, became very aggravated.

gives an interesting consideration about the possible purpose of these expeditions: by the beginning of the 15th century, relations between China of the Ming era and the state of Tamerlane, who even planned a campaign against China, became very aggravated.

Thus, Admiral Zheng He could be entrusted with a diplomatic mission to search for allies across the seas against Timur.

After all, when Tamerlane fell ill in 1404, already having conquered and destroyed cities from Russia to India, there would hardly have been a force in the world capable of coping with him alone...

But already in January 1405, Tamerlane died. It seems that the admiral was not looking for allies against this enemy.

Perhaps the answer lies in some kind of inferiority complex Yongle, who was elevated to the throne by a palace coup. It seems that the illegal "Son of Heaven" simply did not want to wait with folded arms until the tributaries themselves came to bow to him.

The Yongle Emperor sent ships over the horizon in defiance of the main imperial policy, which ordered the son of Heaven to receive ambassadors from the world, and not send them out to the world.

Comparing the expeditions of Vasco da Gama and those of Zheng He, the American historian Robert Finlay writes:

“The expedition of da Gama marked an undeniable turning point in world history, becoming an event symbolizing the advent of the modern era.

Following the Spaniards, the Dutch and the British, the Portuguese began to build an empire in the East ...

In contrast, the Ming expeditions did not entail any changes: no colonies, no new routes, no monopolies, no cultural flourishing and no global unity ... The history of China and world history, probably would not have undergone any changes if Zheng He's expeditions had never taken place at all.

Be that as it may, the active admiral Zheng He remained for China the only great navigator, a symbol of the unexpected openness of the Celestial Empire to the world ...

Sources of information:

1. Wikipedia

2. Dubrovskaya D. "Treasures of Admiral Zheng He"

He finally got rid of the Mongol rule and until 1644 the Ming dynasty ruled the country. During this period, many monarchs left an indelible mark on Chinese history. One of them was Yongle, “the second founder of the dynasty”, during which the Great Ming Empire dramatically changed the political vector and entered a new era of prosperity. During the reign of Yongle (Zhu Di) and the only emperor-artist Xuande (Zhu Zhanji), there lived Zheng He (1371-1435), a great Chinese traveler, diplomat and admiral who made seven long sea voyages across the Indian Ocean.

Causes and Significance of Zheng He's Military Trade Expeditions

European countries and Russia were more focused on expansion. Not surprisingly, most of the great travelers came from the Old World, mostly from countries with strong navies. They searched and found ways in the West Indies, new continents and islands, new colonies and markets. They "went across three seas", sailed on the Mayflower, searched for Eldorado and established outposts in Alaska and Fort Ross, on the inhospitable Pacific and Caribbean islands with bloodthirsty natives.

China has been closed in on itself for most of its history, and the interests of the state usually did not go beyond the territory of its closest neighbors. Often, contacts with overseas merchants and their own coastal shipping off the country's eastern coast were strictly limited. Nevertheless, during the reign of Zhu Di and Zhu Zhanji, China also had its own great traveler, who appeared in the heyday of the Great Ming Empire - Zheng He. The Yongle Emperor was one of the most progressive monarchs in Chinese history. Under him, many now popular ones were built, construction began and completed in, founded and built.

Zhu Di and his grandson Xuande spent a lot of money and energy on diplomatic and military activities to strengthen the influence of the Great Ming Empire outside of "Inner China", limited by the Pacific seas and the Tibetan plateau. Such activity was not characteristic of either their predecessors or their descendants. One of the significant foreign policy steps was seven major military-trading expeditions to southern India, the shores of the Persian Gulf and Northeast Africa. Expeditions of this level were unprecedented in China. If you are in Malacca (Malaysia), pay attention to the majestic statue of Zheng He. The voyages of the famous traveler and admiral had a huge and lasting impact on the historical development of Java, Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula. It is believed that Zheng He's expeditions contributed to increased Chinese emigration to these places and the development of Chinese culture in the region. In modern Chinese historiography, the peaceful voyages of the great traveler are usually contrasted with the aggressive, predatory expeditions of the Western European colonizers.

Biography of Zheng He

At birth, Zheng He was given the name Ma He. The surname Zheng was granted to the future traveler for faithful service by the emperor in 1404. He was born in the village of Hedai, in the central part of Yunnan province, bordering on Indochina and Tibet. Rod Ma came from Central Asia. He's ancestors migrated to China when the Celestial Empire was under the control of the Mongol Yuan dynasty. Subsequently, they became sinicized, retaining the Muslim faith. At the age of 14, Ma He was castrated and became a eunuch in the court of Zhu Di, the future Yongle Emperor. The future admiral probably made his first trip in 1404, when he received the surname Zheng. According to some reports, he was engaged in the construction of warships to fight pirates and visited Japan, which was also interested in defeating the corsairs.

The Seven Journeys of Zheng He

For the first time, the decision to build a squadron was most likely made in 1403. Two years later, the first voyage of a huge fleet of a quarter of a thousand ships with a total crew of about 27,000 people took place. If official Ming history is to be believed, these ships were sheer behemoths, larger than any wooden ships ever built. Seven voyages took place between 1405 and 1433. During this time, the eunuch admiral's fleet visited dozens of countries.

During the first voyage (1405-07), the fleet visited the islands of Java, Sumatra and Sri Lanka, visited the ports of South India. In the next two expeditions, the route differed slightly (1407-1409 and 1409-1411). During subsequent voyages, Zheng He and the squadrons subordinate to him reached the Horn of Africa (the region of present-day Somalia), the island of Hormuz (Persia-Iran), and the coast of the Red Sea. After Yongle's death, there was a break for several years. At this time, Zheng He leads the Nanjing garrison. At Xuande, swimming resumes again. During the last expedition, the admiral no longer personally enters many countries, sending individual ships and squadrons there. Long journeys are already weighing on Zhong He, and he returns to China even before the campaign is completed.

During their voyages, the admiral and his subordinates were actively engaged in establishing and improving diplomatic and trade relations with many countries, compiled navigational charts and collected detailed information about the states and territories they visited. Subsequently, the work of the Chinese admiral was used by many European travelers who were not yet familiar with the northern waterways Indian Ocean. Today, many Chinese communities in Indonesia and Malaysia consider Zhong He almost a saint. Many temples and monuments have been erected in his honor.

magazine LIFE, then in 14th place, just behind Hitler, we will meet the name of Zheng He. Who is he and what did he do to deserve this calling? We all know the era of the Great Discoveries, Magellan, Columbus, Portugal and Spain divide the whole world in half and milk it to the maximum. And what did Greater China do 100 years earlier in the Ming Dynasty?

Zheng He's fleet made 7 voyages from China to Southeast Asia, Ceylon and South India. During some journeys, the fleet reached Ormuz in Persia, and its individual squadrons reached several ports in Arabia and East Africa.

According to Gavin Menzies, author of Zheng He's latest book, 1421, he sailed across the Indian Ocean to Mecca, the Persian Gulf, East Africa, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), Arabia and across the Indian Ocean decades before Christopher Columbus or Vasco da Gama, and his ships were five times larger!

According to historians, among the reasons for organizing these expeditions was both the desire of Zhu Di to gain international recognition of the Ming dynasty, which replaced the Mongol Yuan dynasty, as the new ruling dynasty of the "Middle State", and the assertion of the legitimacy of his own stay on the throne, usurped by him from his nephew of Zhu Yunwen. The latter factor may have been exacerbated by rumors that he did not die in the fire of the Nanjing Imperial Palace, but was able to escape and is hiding somewhere in China or beyond. The official "History of Ming" (compiled almost 300 years later) states that the search for the missing emperor was one of the goals of Zheng He's expeditions as well. In addition, if Zhu Yunwen was alive and looking for support abroad, Zheng He's expedition could interfere with his plans and show who is the true ruler in China.

Stationary full scale model of a "medium sized treasure ship" (63.25 m long) built ca. 2005 at the site of the former Longjiang Shipyard in Nanjing. The model has reinforced concrete walls with wood paneling.

The sailing fleet, led by the eunuch Zheng He, was built at the beginning of the 15th century in the Chinese Ming Empire, and consisted of no less than 250 ships. This fleet was also called golden.

There are different opinions among historians about the number of ships in Zheng He's fleet. For example, the author of the popular biography of Zheng He (Levathes 1994, p. 82), following many other authors (for example, the authoritative history of the Ming era (Chan 1988, p. 233), calculates the composition of the fleet that participated in the first expedition of Zheng He (1405 -1407) as 317 ships, adding up 62 treasure ships mentioned in the "History of Ming" with "250 ships" and "5 ships" for ocean voyages, the order of which is mentioned in other sources of the period. However, E. Dreyer, analyzing the sources, believes that it is incorrect to add up figures from different sources in this way, and in reality the mention of "250 ships" means all the ships ordered for this expedition.

Baochuan: length - 134 meters, width - 55 meters, displacement - about 30,000 tons, crew - about 1,000 people

1. Cabin of Admiral Zheng He

2. Ship altar. The priests constantly burned incense on it - so they appeased the gods

3. Hold. Zheng He's ships were full of porcelain, jewelry, and other gifts for foreign rulers and a display of the emperor's might.

4. The rudder of the ship was equal in height to a four-story house. To bring it into action, a complex system of blocks and levers was used.

5. Observation deck. Standing on it, the navigators followed the pattern of the constellations, checked the course and measured the speed of the ship.

6. Waterline. The displacement of the baochuan is many times greater than that of contemporary European ships

7. The sails woven from bamboo mats opened like a fan and provided a high windage of the vessel

"Santa Maria" Columbus: length - 25 meters, width - about 9 meters, displacement - 100 tons, crew - 40 people

The beauty and pride of the squadron, baochuan (literally “precious ships” or “treasuries”), were built at the so-called “precious ships shipyard” (baochuanchang) on the Qinhuai River in Nanjing. It is this last fact, in particular, that determines that the draft of the junks, with their gigantic size, was not very deep - otherwise they simply would not have passed into the sea through this tributary of the Yangtze. And finally, everything was ready. On July 11, 1405, in the Chronicle of Emperor Taizong (one of the ritual names of Yongle), a simple entry was made: “The palace dignitary Zheng He and others were sent to the countries of the Western (Indian) Ocean with letters from the emperor and gifts for their kings - gold brocade, patterned silks, colored silk gauze - all according to their status. In total, the armada included up to 255 ships with 27,800 people on board.

A junk from a Sung-era drawing shows the traditional construction of a Chinese flat-bottomed vessel. In the absence of a keel, a large rudder (at the stern) and side screws help the stability of the vessel.

Chinese shipbuilders realized that the sheer size of the ships would make them difficult to maneuver, and so they installed a balance rudder that could be raised and lowered for greater stability. Modern shipbuilders do not know how the Chinese built a ship's hull without the use of iron, which could carry a vessel of 400 feet, and some even doubted that such ships even existed at that time. However, in 1962, in the ruins of one of the shipyards of the Ming Dynasty in Nanjing, a ruder post of a treasure ship was discovered, which was thirty-six feet in length. Using the proportions of a typical traditional junk (a typical Chinese ship), after making repeated calculations, the estimated hull for such a rudder was five hundred feet (152.5 meters).

Rudder on a modern model of a treasure ship (Longjiang shipyard)

What is strange, comparing the expeditions of Vasco da Gama and the expedition of Zheng He, the American historian Robert Finlay writes: “The da Gama expedition marked an undeniable turning point in world history, becoming an event symbolizing the onset of the New Age. Following the Spaniards, the Dutch and the British, the Portuguese began to build an empire in the East ... In contrast, the Ming expeditions did not entail any changes: no colonies, no new routes, no monopolies, no cultural flourishing and no global unity ... The history of China and the world history would probably not have changed if Zheng He's expeditions had never taken place at all."

Christopher Columbus' sailboat compared to Zheng He's (ft).

In connection with the voyages of Zheng He, Western authors often ask the question: “How did it happen that European civilization in a couple of centuries drew the whole world into its sphere of influence, and China, although it began large-scale ocean voyages earlier and with a much larger fleet than Columbus and Magellan soon stopped such expeditions and switched to a policy of isolationism?", "What would happen if Vasco da Gama met a Chinese fleet on his way, similar to Zheng He's fleet?"

Popular literature even suggested that Zheng He was the prototype of Sinbad the Sailor. Evidence of this is sought in the similarity of sound between the names Sinbad and Sanbao and in the fact that both made seven sea voyages.

Ma San-bao, Arab. Haji Mahmud. 1371/1376, Kunyang County (modern Jinning, Yunnan Province) - 1433/1435. Great navigator, naval commander, dignitary, diplomat and literary character. Genus. the youngest son in a noble Muslim (see vol. 2, pp. 318-325) family, where he had two sisters and a brother, and his father and grandfather made the Hajj to Mecca. In 1382 he was castrated and made a eunuch, from 1385 he served the son of the emperor. Zhu Yuan-zhang to the commander Zhu Di, who became an imp. Cheng-zu (r. 1402-1424) and in 1404 for his merits in the struggle for the throne, he was awarded the surname Zheng (called. ancient kingdom) and appointed "highest eunuch" (tai jian), and soon - ambassador to Japan and admiral. Implementation of dip. The missions were facilitated by the fact that Zheng He professed two worlds. religions - Islam and Buddhism. The latter is evidenced by his name San-bao (Three Jewels; see San-bao). In 1405-1433, a huge squadron under the command of Zheng He made seven unprecedented (in terms of the number of participants, ships, places visited, range and duration) voyages through South China. sea in the Indus. ocean, reached Africa 80 years earlier than Vasco da Gama, and may have entered the Red Sea. Despite the abundance of information about Zheng He in the East. or T. sources, about privacy Very little is known about the circumstances of death. He had a house in Nanjing and, apparently, an adopted son, Zheng Hao 灏, who appeared in 1489 as a claimant to the inheritance. It was traditionally believed that Zheng He died 2-3 years after returning from the last expedition at the age of 65 in 1435 or 1436, but there is no evidence of this by contemporaries. In "Tong zhi Shangjiang 同治上江 liang xian zhi" ("Treatise on two jointly administered counties of the Upper River [Yangtze]", preface 1874), it is said about his death in Calicut (Kozhikode) and burial in Nyushoushan near Nanjing, from which it follows that he died in 1433. However, in decree. there is no grave sign with his name, and a grave of another eunuch of the Ming era and namesake - Zheng Qiang 强 is identified nearby.

Sources:

Fei Xin. Xing cha sheng lan jiao-zhu (“Capturing views / Full view [with] star-guided ships” with reconciliation and commentary) / St. and comm. Feng Cheng-jun. Beijing, 1954; Ma Huang. Ying ya sheng lan jiao-zhu (“Fascinating views / A complete overview of the ocean shores” with reconciliation and commentary) / St. and comm. Feng Cheng-jun. Beijing, 1955; Gong Chen. Xi yang fan guo zhi (Treatise on the barbarian states of the Western Ocean). Beijing, 1961; Zheng He han hai tu (Image of Zheng He's voyages) / Ed. Xiang Yes. Beijing, 1961; Rockhill W. Notes on the Relations and Trade of the China with Eastern Archipelago and the Coast of Indian Ocean in the XV Century// TP. 1914-1915. Vol. 15-16; Ma Huang. Ying-yai sheng-lan: The Over-all Survey on the Ocean's Shores (1433) / Tr. by J.V.G. Mills. Cambridge, 1970; Fei Xin. Marvellous Visions from the Star Raft (Xing-cha sheng-lan) / Tr. by J.V.G. Mills. Wiesbaden, 1996.

Literature:

Zaichikov V.T. Travelers of ancient China and geographical research in the People's Republic of China. M., 1955; Magidovich I.P. Essays on the history of geographical discoveries. M., 1957; Menzies G. 1421 - the year China discovered the world. M., 2004; Light Ya.M. Long-distance voyages of Chinese sailors in the first half. XV century // Issues of the history of natural science and technology. Issue. 3. M., 1957; Bao Tsung-peng. Zheng He xia xi yang zhi bao chuan kao (Research of Zheng He's miraculous voyage to the Western Ocean). Taipei, 1961; Wang Chengzu. Zhongguo dili-xue shi (xian Qin zhi Ming Dai) (History of Chinese geographical science (from pre-Qin [times] to the Ming era)). Beijing, 1988, p. 115-124; Lee Shi-hou. Zheng He jia pu kao shi (Research with comments on Zheng He's family annals). Kunming, 1937; Jin Yun-ming. Zheng He qi ci xi xi yang nian yue kao zheng (A critical study of the dates of Zheng He's seven voyages to the Western Ocean) // Fujian wenhua (Culture of Fujian), No. 26 (12/25/1937); Zhai Zhong-i. Zhongguo gudai dili-xuejia ji luixing-jia (Ancient Chinese geographers and travelers). Jinan, 1964; Zheng Hesheng. Zheng He and shi hui bian (Summary of Zheng He's achievements). Shanghai, 1948; Chang Kuei-sheng. A Re-examination of the Earliest Chinese Map of Africa // Papers of the Michigan Academy of Science, Arts, and Letters. XLII. Michigan, 1957; idem. Cheng Ho // Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368-1644. Vol. I.N.Y., L., 1976, p. 194-200; Dreyer E.L. Zheng He: China and the Oceans in the Early Ming, 1405-1433. N. Y. 2006; Duyvendak J.J.L. Ma Huan Re-examined. Amsterdam, 1933; idem. The True Dates of Chinese Maritime Expeditions in the Early XV Century // TP. 1939 Vol. 34, liver 5; idem. The Mi-li-kao Identified // TP. 1940 Vol. 35; idem. Achinese Divina Commedia // TP. 1952 Vol. 41; idem. Desultory Notes on the His-yang chi // TP. 1954 Vol. 42; idem. China`s Discovery of Africa. L., 1949; Gaillard L. Nankin d'alors et d'aujour-d'hui. Shanghai, 1903; Levathes L. When China Ruled the Seas: The Treasure Fleet of the Dragon Throne, 1405-1433, Oxford., 1997; Lombard-Salmon C. La communauté chinoise de Makasar // TP. 1969 Vol. 55; Menzies G. 1421: The Year China Discovered the World. L., 2002; Mulder W.Z. The “Wu Pei Chih” Charts // TP. 1944 Vol. 37; Pelliot P. Les grands voyages maritimes chinois au début du XVe siècle // TP. 1933 Vol. thirty; idem. Notes additionelles sur Tcheng Houo // TP. 1935 Vol. 31; idem. Encore à propos des voyages de Tcheng Houo // TP. 1936 Vol. 32; idem. Les caractères de transcription wo ou wa et pai // TP. 1944 Vol. 37; Purcell V. The Chinese in Southeast Asia. L., N.Y., Toronto, 1951; Stevens K. Three Chinese Deities // JRAS Hong Kong br., Vol. 12, 1972; Wiethoff B. Die chinesische Seeverbotspolitik und der private Uborseehandel von 1368 bis 1567. Hamburg, 1963; Willets W. The Maritime Adventures of Grand Eunuch Ho // Journal of South-East Asian History. 1964 Vol. V, no. 2.

Art. publ.: Spiritual culture of China: encyclopedia: in 5 volumes / ch. ed. M.L. Titarenko; Institute Far East. - M .: Vost. lit., 2006-. T. 5. Science, technical and military thought, health care and education / ed. M.L. Titarenko and others - 2009. - 1055 p. pp. 950-951.