Where did Roosevelt live during the Yalta Conference. Institute of Russian Sociological Research

STALIN - ROOSEVELT - CHURCHILL: THE "BIG THREE" THROUGH THE PRISM OF WAR CORRESPONDENCE

V. O. Pechatnov*

The article, written on the basis of new documents from the archive of I. V. Stalin in the RGASPI and the Foreign Policy Archive of the Russian Foreign Ministry, sheds new light on Stalin's correspondence with F. Roosevelt and W. Churchill during the Second World War. It is traced how (together with V. M. Molotov) these messages were compiled, Stalin's direct contribution to this correspondence is clarified, based on the analysis of Stalin's editing, the true motives and priorities of the great dictator on the problems of the second front, lend-lease, the Polish question, meetings in top, as well as differences in his approach to relations with Roosevelt and Churchill. Based on the dispatches of the USSR Ambassador in London, I. M. Maisky, Churchill's direct reaction to Stalin's messages can be traced. The article shows that an in-depth analysis of the famous correspondence opens up new opportunities for studying the allied diplomacy of the war years.

Key words: Stalin, Roosevelt, Churchill, Big Three, anti-Hitler coalition, second front.

Key words: Stalin, Roosevelt, Churchill, the Big Three, anti-Hitler coalition, World War II, second front.

In the relationship between the leaders of the anti-Hitlers, their place is occupied by their famous correspondence of the military

coalition during the Second World War. Nevertheless, this large and complex topic is given, there is a sea of literature, many memoirs are not easily exhausted, and it is the correspondence that opens

and other sources, among which the most important new opportunities for its additional study

* Pechatnov Vladimir Olegovich - Doctor of Historical Sciences, Professor, Head of the Department of History of European and American Politics, MGIMO (U) of the Russian Foreign Ministry, e-mail: [email protected]

cheniya. The fact is that until now relatively little is known about how these messages were actually written and perceived, with the exception of the correspondence between F. Roosevelt and W. Churchill, which was studied in detail and commented on by the famous American historian of the Second World War, W. Kimball1. The other two sides of this epistolary triangle - Stalin-Roosevelt and Stalin-Churchill are just beginning to be studied by historians2. Although the texts of the messages themselves have long been known and often cited, knowledge of the background of the correspondence helps to better understand their often hidden meaning and thus enriches our understanding of the true relationship within the Big Three.

The main contours of these relations have been studied quite well, but even the most seemingly insignificant details and semitones are important here, because in such a delicate and responsible matter as tripartite diplomacy at the highest level, they also acquired serious political significance. Correspondence of the "Big Three" in this sense is generally unique: perhaps, in the entire history of diplomacy, there is no analogue to it either in meaning, or in format, or in terms of the caliber and historical role of the correspondents themselves. Correspondence has become for them the main channel of communication, providing direct personal contact in wartime, which is critical for the fate of the whole world. In its course, the leaders not only informed each other, but also coordinated positions, defended the interests of their countries, sometimes engaging in heated polemics.

The specificity of this triangle was also that it was not "isosceles", since Roosevelt and Churchill were in much closer relations with each other than with Stalin. Their bilateral correspondence (nearly two thousand messages for 1939-1945) is more than twice their correspondence with the Soviet leader, they met much more often during the war years and kept in touch by phone, not to mention the Anglo-American solidarity in the majority issues of allied diplomacy. The degree of awareness of the members of the “troika” about the actions of their partners was also unequal: if Roosevelt and Churchill constantly kept each other informed about their correspondence with the Kremlin, then Stalin could only guess about the content of their correspondence between themselves or rely on the work of his intelligence in this regard. This asymmetry put him in a less advantageous position compared to his partners.

The technology of preparing messages in all three capitals was also different. The vast majority of the epistles were prepared by assistants, but even here

there were notable differences: firstly, Roosevelt and Churchill had many more co-authors than Stalin, who relied mainly on V. M. Molotov (for example, a total of 17 people participated in correspondence with the British prime minister from the American side , besides the president himself)3; secondly, Stalin interfered much more in the prepared draft messages and more often wrote them with his own hand than Roosevelt and Churchill. Establishing the true authorship of the messages, in addition to the purely archeographic side of the matter, is important for clarifying the motives and way of thinking of the main characters, their direct contribution to the correspondence. Particularly interesting, as we shall see, is the analysis of the corrections that the leaders made to the prepared draft messages.

In terms of the degree of closeness and personalization of correspondence, the Soviet side occupied the first place, where the content of the messages was entirely determined by the Stalin-Molotov tandem and only occasionally brought to the attention of individual senior members of the Politburo on issues of their competence. The British practice was the most open and collegial: the messages of Roosevelt and especially Stalin were regularly discussed at cabinet meetings, which then instructed (usually the Ministry of Foreign Affairs) to prepare a response of one kind or another. The messages themselves were regularly sent to the king and key cabinet members. The American procedure was closer to the Soviet one, with the difference that many more people took part in the preparation of the draft messages, among which not diplomats predominated, but the military and personal assistants to the president, primarily Mr. Hopkins. Through all three channels, the messages, as a rule, were transmitted by cipher telegrams through their embassies and handed over to the addressee in the original language.

Let us turn to the background of Stalin's correspondence with Roosevelt and Churchill, since it is precisely the "Stalinist angle" of this correspondence that remains the least studied so far. The first thing that draws attention to comparative analysis compiling Stalin's messages to Washington and London is a very subtle differentiation that the great dictator makes in his treatment of his main addressees. Molotov's drafts, as a rule, did not make this distinction, but Stalin, as we shall see, corrects them in the direction of "warming" and respectfulness in the case of Roosevelt, and, on the contrary, often toughens them in the case of Churchill. This differentiation was, of course, not accidental and reflected Stalin's different attitude towards the two leaders of the Anglo-American world.

His attitude towards Roosevelt was determined by a whole bunch of objective and subjective factors: the superior military and economic power of the United States, a more positive image of America compared to the old opponent of the tsarist and Soviet Russia Great Britain, less potential for conflict in Soviet-American relations compared to Anglo-Soviet relations, Roosevelt's personal reputation as the initiator of diplomatic recognition of the USSR and assistance to it in the form of lend-lease, in contrast to the ardent anti-Soviet, the inspirer of the Entente campaign during the Civil War, Churchill4. Personal qualities also mattered - Roosevelt's democratic courtesy and the bristling arrogance of the British prime minister, which manifested themselves both in correspondence and in personal communication of the "Big Three". During the talks in Tehran and Yalta, as confirmed by the chief intermediary between Roosevelt and Stalin, US Ambassador to Moscow A. Harriman, the latter "treated the President as the eldest of the participants"5; he was much more considerate with Roosevelt than with Churchill - he often agreed with him, and if he objected, then with restraint, never allowing himself the obvious barbs or rude jokes that fell to the lot of an Englishman. Probably, the choice of different nicknames for both leaders in the reports of Soviet intelligence was not accidental - “Captain” (Roosevelt) and “Boar” (Churchill) - the scouts were well aware of the tastes and preferences of the main addressee of their information.

Not even trusting himself, accustomed to seeing enemies in his allies, Stalin, of course, did not fully trust Roosevelt either, especially since, thanks to well-organized intelligence, he clearly saw his double game (primarily with the development of atomic weapons and delaying the opening of a second front). ). And yet the American president was for him the main and most convenient partner, who could be used as a certain counterbalance to Churchill, playing on the Anglo-American differences6. However, for all the nuances of his correspondence with the Anglo-Americans, Stalin was well aware of the intimate nature of the special relationship between Roosevelt and Churchill and avoided telling one what he wanted to hide from the other. Now let's see how it all looked in real life, taking as examples the most important issues, raised in the correspondence of the "big three".

The first serious complication in allied relations arose in the summer of 1942 in connection with London's decision to suspend northern convoys.

due to their heavy losses from German attacks. Moreover, in the draft of his message to Stalin, Churchill linked this step with the need to accumulate forces to open a second front in 1943, which ran counter to the May agreements on its opening in 1942, reached during Molotov's visits to London and Washington. Churchill sent this draft for approval to Roosevelt, who reluctantly agreed with the proposed text7. Having received a stern answer from Stalin (dated July 23), the allies became thoughtful. Churchill, in a message to Roosevelt, proposed limiting himself to sending Stalin his memorandum, handed to Molotov in May, with his reservations about the possibility of opening a second front in

1942 Roosevelt found this insufficient. “... The answer to Stalin,” he wrote, “should be thought out very carefully. We must always keep in mind the personality of our ally and the difficult and dangerous situation in which he finds himself. One cannot expect a universal view of war from a man whose country has been invaded by the enemy. I think we should try to put ourselves in his shoes.”8 As a confidence-building measure, the President proposed to let Stalin in on the strategic plans for

1942 related to Operation Torch for the invasion of North Africa. Churchill decided to meet with Stalin for a frank explanation on his way back from Cairo.

This difficult mission of Churchill has been described in detail in the literature, records of his conversations with Stalin9 have been published, the whole range of Moscow experiences of Churchill is well known, who was first crushed by the Stalinist cold, and then, especially during the famous night conversation at the leader’s apartment, was fascinated by the hospitality of the owner of the Kremlin and his instant insight into the essence and strategic advantages of Fakel. Churchill himself, in a detailed report to Roosevelt, wrote with sincere relief that the Russians "swallowed this bitter pill", and he managed to establish friendly personal relations with Stalin.

However, despite outward cordiality, Stalin seems to have only confirmed his deep distrust of Churchill. This was facilitated by the critical deterioration of the situation near Stalingrad and the story of the missing 154 "Aircobras" - American fighters intended for the Stalingrad Front, but secretly transferred to the Americans at the direction of Churchill for the needs of Operation Torch. In mid-October, Stalin telegraphed the ambassador in London, I. M. Maisky: “In Moscow, we get the impression that Churchill is heading for the defeat of the USSR in order to

then come to terms with Hitler's or Brüning's Germany at the expense of our country. In response, Maisky (a rare case) even tried to convince the "Supreme", arguing that Churchill did not set such a task for himself, although "objectively" his policy could lead to this. Stalin (which also happened rarely) partly agreed with Maisky, but remained unconvinced about the perfidy of the British prime minister. “Churchill apparently belongs to the number of those figures who easily make a promise in order to just as easily forget about it or even grossly violate it ... Well, from now on we will know what kind of allies we are dealing with”11.

In the same telegram to Maisky, Stalin wrote that he "had little faith" in Operation Torch, but it developed successfully, exceeding the expectations of the Anglo-American command itself. The success of the allies was helped by a cynical deal between the Americans and the commander of the Vichy regime in North Africa, Admiral Darlan, who, in exchange for recognition of him in this capacity by the Anglo-Americans, refused to resist their landing and even facilitated it. In response to a message from Churchill with a contemptuous mention

about this deal with the “swindler Darlan”, Molotov drafted a message in which he decided to finally stigmatize the corrupt Frenchman: “As for Darlan, suspicions about him seem to me quite legitimate. In any case, lasting solutions in North Africa should not be based on Darlan and his like, but on those who can be an honest ally in the uncompromising struggle against Hitler's tyranny, with which, I am sure, you agree. Stalin crossed out Molotov's angry passage, which seemed to him, apparently, inappropriate prudishness, and replaced it with his very expressive one: “As for Darlan, it seems to me that the Americans skillfully used him to facilitate the occupation of North and West Africa. Military diplomacy should be able to use for military purposes not only Darlanov, but also the devil with his grandmother. The straightforward Molotov was far from the Machiavellian flexibility of the "Master"!

Stalin makes another characteristic addition to the same message. In response to Churchill's vague reference to "constant preparations" in the Pas de Calais and new bombardments of Germany, he interjects: "I hope that this does not mean abandoning your promise in Moscow to set up a second front in Western Europe in the spring

1943"13. As you can see, Stalin does not miss the opportunity to remind the allies of this promise, not yet knowing that they are already preparing to break it.

Although the double game on the issue of a second front was played jointly by Roosevelt and Churchill, the latter was its main inspirer, "leading Roosevelt in tow," in the figurative expression of the Soviet Ambassador to the United States M. M. Litvinov14. The American president, for his part, tried to soften Moscow's painful reaction to this game, including by more actively involving the Soviet military command in Anglo-American strategic planning, as well as by holding a trilateral summit. First, he pronounces these ideas with a skeptical Churchill, and in early December 1942, for the first time, he proposes such a meeting "in the near future" to Stalin himself15. He was in no hurry to agree, striving to come to this meeting as strengthened as possible by new military victories, capable of predetermining its success and even the venue itself. Roosevelt, as Churchill confided to Maisky, was very annoyed by this Stalinist intractability. “The President asked me what was the reason for Stalin's refusal to come. I told the president: Stalin is a realist. You can't get through it with words. If he came, the first question he would ask you and me would be: “Well, how many Germans did you kill in 1942? And how many do you expect to kill in 1943? What would we say to you? We don't know ourselves. This was clear to Stalin from the very beginning - what was the point of him going to the meeting? Especially since he really does do big things at home.

In this case, the prime minister did not dissemble. He did indeed write something similar to Roosevelt at the end of November: “I can say in advance what the position of the Russians will be. They will ask you and me: “How many German divisions can you forge in the summer of 1943? And how much did you shackle in 1942?” They will certainly demand a strong second front in 1943 in the form of a massive invasion of the continent from the west, south, or both. There really was nothing to answer to this, especially since the promised opening of a “strong second front” was again pushed back.

Stalin caught the first disturbing hint of this in Churchill's message of March 11, 1943, in which the prime minister conditioned the start of the operation in northern France by "sufficient weakening" of the enemy: he circles this phrase with a double line and puts a bold question mark in the margin. The leader's suspicions were quickly conveyed to Molotov, who prepared a draft response with an insistent request to eliminate the "uncertainty" of the prime minister's statements,

causing "alarm" in the Kremlin. However, for the time being, Stalin decided to soften the tone of the message somewhat, adding to the harsh reminder of the importance of the invasion of France in 1943, a conciliatory phrase that he "recognizes the difficulties" of the Anglo-Americans in carrying out such an operation.

At the end of March, Roosevelt and Churchill decided to stop sending northern sea convoys to Murmansk and Arkhangelsk in view of the heavy losses from the German submarines lying in wait for them. Having plucked up courage, Churchill delivered this difficult news to Stalin in a message dated March 30, corrected by Roosevelt. The next day, the prime minister received Maisky and told him about this decision, testing the Soviet reaction on him. “I decided to tell Stalin directly what I have,” he explained. - Never mislead an ally. We are warriors. We must be able to courageously face even the most unpleasant news. "Won't this lead to a rupture between me and Stalin?" Churchill asked with unconcealed anxiety. “I can’t say anything for Comrade Stalin,” the ambassador answered, “he will say it himself. In one thing I have no doubt that the cessation of the convoys will evoke very strong feelings in Comrade Stalin. Churchill continued: “Anything, but not a break. I don't want a break, I want to work with you. I am sure that I will be able to work with Stalin. I have no doubt that if I am destined to live longer, I can be very useful to you in establishing friendly relations with the United States. We, the three great powers, must at all costs ensure friendly cooperation after the war.

In the Kremlin, Maisky's excited dispatch was received on April 1, the day after the receipt of Churchill's message. Thus, Stalin could answer him already taking into account the ambassador's information about the fears and hopes of his British correspondent. Perhaps that is why his response message to Churchill on April 2 was so laconic - Stalin qualified this "unexpected act as a catastrophic reduction in the supply of military raw materials and weapons to the Soviet Union by Great Britain and the United States." “It is clear,” he concluded sparingly, “that this circumstance cannot but affect the position of the Soviet troops.”21 Churchill breathed a sigh of relief: “I consider Stalin's message a natural and stoic response,” he wrote to Roosevelt. - His last sentence for me means only one thing - "the Soviet army will be worse off and will have to suffer more"22.

A much more acute crisis in allied relations erupted in June 1943, when Ruz-

Welt and Churchill, after their third Washington conference (codenamed "Trident"), informed Stalin about another postponement of the second front. This time it was in Roosevelt's message of June 4, to which Stalin responded harshly but restrainedly, emphasizing that this decision "creates exceptional difficulties for Soviet Union". Stalin even softened the tone of the message: the warning contained in Molotov's draft that the decision of the allies "will have the most serious consequences and decisive for the further course of the war" is replaced by "which could have grave consequences for the further course of the war"23. Along the way, in an indirect form, the "decisive importance" of the actions of the allies for the course of the war was generally denied, as if leaving this role only to the Soviet Union.

A much more severe rebuff awaited Churchill when he, in an answer coordinated with the White House, tried to give a detailed justification for the Anglo-American actions. The Kremlin recluse, with quotations from concrete statements by the Anglo-Americans, reminded him of all previous broken promises. Churchill's arguments were subjected to resolute and justified criticism, and at the end of the message a downright forged phrase was inserted: “I must tell you that it is not just about disappointing the Soviet Government, but about maintaining its confidence in the allies, which is being severely tested. We must not forget that we are talking on saving millions of lives in the occupied areas Western Europe and Russia and about the reduction of the colossal losses of the Soviet armies, in comparison with which the victims of the Anglo-American troops are a small amount”24.

Maisky's dispatch preserved for historians a picture of Churchill's violent reaction, most of all stung by Stalin's accusation of deliberate deceit. “In the course of the conversation,” the ambassador reported, “Churchill returned several times to that phrase in Comrade Stalin’s message, which refers to “trust in the allies” (at the very end of the message). This phrase clearly haunted Churchill and caused him great embarrassment. The prime minister even questioned the advisability of continuing the correspondence, which, he said, "only leads to friction and mutual irritation." Maisky managed to reassure him somewhat by reminding him of the enormous sacrifices of the Soviet Union and the importance of maintaining direct contact between the Allied leaders at a critical moment in the war. Churchill, in his words, "began to gradually go limp" and went over to

justifying his actions, as if continuing a dispute in absentia with Stalin: “Although Comrade Stalin’s message is a very skillful polemical document,” he said according to Maisky, “it does not fully take into account the actual state of affairs ... At the moment when Churchill gave Comrade Stalin his promises, he quite sincerely believed in the possibility of their implementation. There was no conscious rubbing of the glasses. “But we are not gods,” Churchill continued, “and we make mistakes. The war is full of all sorts of surprises. It is unlikely that these excuses were able to convince Stalin of something. As a warning to the allies, at the end of June he recalled the popular Soviet ambassadors in the West - Maisky from London and Litvinov from Washington.

WITH special attention Stalin corresponded on the question of the summit meeting. His dislike of long-distance travel and obsession with the prestige of the USSR led to a stubborn refusal to meet Roosevelt and Churchill away from Soviet territory. In his draft message to Roosevelt of August 8

1943, he writes a long passage with a proposal to arrange such a meeting "either in Astrakhan or in Arkhangelsk"26. In late August, he agrees to an Allied proposal to hold a meeting of the Big Three foreign ministers ahead of the summit. Churchill proposed to hold it in London, Roosevelt - in Casablanca or Tunisia. In a reply message to Roosevelt on this subject dated September 8, Stalin adds the key phrase to the Molotov project: "... moreover, I propose Moscow as the meeting place"27. Despite subsequent attempts by Roosevelt to replay this meeting place, Stalin managed to get his way. Thus was born the Moscow Conference of Foreign Ministers of the three Allied Powers, which became the prologue to the Tehran meeting of the Big Three.

But even on the way to this meeting, Stalin does not miss the opportunity to pull the Anglo-Saxons when he sees the slightest infringement of Soviet prestige or interests by them. Churchill is particularly hard hit, who, as the Kremlin is well aware from reports from Soviet intelligence and diplomacy, continued to persuade Roosevelt to delay the crossing of the English Channel. Stalin's message to Churchill of October 13 is indicative, in the draft of which he introduces a significant revision. Instead of Molotov's gratitude for the message about sending additional northern convoys, he inserts the following phrase - this message is "depreciated" by the Prime Minister's statement that sending these convoys is not a fulfillment of an obligation, but a manifestation of the good will of the British

Tan side. In refusing Churchill's request for more British naval personnel in northern Russia, Stalin steps up his rebuke of the British for the "unacceptable" behavior of British troops in Arkhangelsk and Murmansk who are trying to recruit Soviet people for intelligence purposes: Molotov's roundabout statement about the use by the British of the "temptations of material wealth" ” he replaces with an angry accusation - “such phenomena, insulting to Soviet people, naturally give rise to incidents.”28. Churchill was so outraged by this "offensive" message, in his words, that he refused not only to answer it, but even to accept it, returning the document to the new Soviet ambassador F.T. Gusev with the explanation that E. Eden would deal with this issue at the upcoming ministerial conference foreign affairs in Moscow (there, by the way, the request of the British was granted)29.

The Tehran conference, at which, despite Churchill's resistance, the question of a second front was finally resolved, brings a clear thaw in relations between the Big Three. In his first message after Tehran to Churchill and Roosevelt on December 10, Stalin even inserts the unusual conclusion “Hi!” Most noticeable is the warming tone of his treatment of Roosevelt. Summing up the results of the meeting in a message to the president of December 6, Stalin adds the following words to the Molotov project (highlighted in italics - author): “Now there is confidence that our peoples will act together in unison both at the present time and after the end of this war. I wish the best infantry to you and your armed forces in the upcoming responsible operations.

On December 7, Headquarters received a message from Roosevelt about the appointment of General D. Eisenhower as commander of the operation to force the Channel (codenamed "Overlord"). In Tehran, Stalin insisted on the speedy appointment of an invasion commander, and the fact that he became the authoritative Eisenhower pleased him doubly, as confirmation of the seriousness of the allies' intentions. In addition, on the same day, in a separate message, Roosevelt and Churchill informed Stalin about additional measures to expand the scale of the upcoming operation. Therefore, on December 10, he answers Roosevelt with a brief message, in the draft of which he inserts the following words by hand (highlighted in italics - author): “I received your message on the appointment of General Eisenhower. Greetings

appointment of General Eisenhower. I wish him success in the preparation and implementation of the upcoming decisive operations. (Stalin, as we see, raises the significance of the landing of the allies in France in comparison with the previous message.)

As for Churchill, already in January, Stalin removed Molotov's Tehran sentiments from the draft message to the prime minister, deleting his final paragraph: “Your reports that you are working hard to ensure the success of the decision on a second front are very encouraging. This means that soon the enemy will understand how great is the role of Tehran in this great war”32.

Especially closely Stalin controlled the correspondence on the Polish question, which became the main stumbling block in relations between the allies after the second front. Here he invariably toughens Molotov's assessments of the Polish government in exile and the positions of the allies, without differentiating their tonality depending on the addressee, although Churchill remains the main target of his criticism. The Prime Minister gave grounds for this. Although the Allies agreed in principle in Tehran to change eastern border Poland along the Curzon Line, Churchill, in his message to Stalin on March 21, announced Britain's refusal to recognize the transfer of "territories produced by force" (a transparent allusion to the annexation of Western Ukraine and Belarus to the USSR in 1939) and announced that he was going to openly say this in the British Parliament.

Stalin could not leave this attack unanswered. He was especially offended by the qualification of the actions of the Red Army as a forcible seizure of Polish territory. Therefore, he makes the following change to Molotov's draft (in italics -author): "I understand this in such a way that you expose the Soviet Union as a force hostile to Poland and, in fact, deny the liberation nature of the Soviet Union's war against German aggression." Churchill was also accused of a flagrant violation of the Tehran agreements and that he was not making sufficient efforts to force the "Londoners" to recognize the legitimacy of the Soviet demands. The message ended with a significant warning that "the method of threats and discredit, if continued, will not be conducive to our cooperation"33.

This time, Churchill evaded further polemics. “In my opinion, he (Stalin - author) barks more than bites,” he shared with Roosevelt and, on the recommendation of the cabinet, instructed

to make a response statement to the British Ambassador in Moscow A. Kerr34.

The long-awaited opening of the second front smoothed out inter-allied contradictions for a while. Stalin kept his promise to support the actions of the allies with a new Soviet offensive on the Soviet-German front. In a message to Churchill dated June 9, he directly names the date of the start of the first round of this offensive - June 10 (instead of the phrase “in the coming days” proposed by Molotov), realizing how important this accurate information is for the Allies. On the same day, Churchill answered with enthusiasm: “The whole world can see the embodiment of Tehran's plans in our concerted attacks against our common enemy. May all good luck and happiness accompany the Soviet armies. Roosevelt's reaction was more restrained: "Uncle Joe's plans are very promising," he wrote to Churchill, "although they come a little later than we hoped, in the end it may be for the better" 3b. What did the President mean in this mysterious final phrase , added by him to the text prepared by his assistant, Admiral W. Leahy? Apparently, it is worth agreeing with W. Kimball's assumption that Roosevelt was worried about the too far advance of the Red Army deep into Europe37. We saw this anxiety in Moscow as well. As Stalin himself later said in a conversation with M. Thorez, “... Of course, the Anglo-Americans could not allow such a scandal that the Red Army would liberate Paris, and they would sit on the shores of Africa”38.

But even understanding the self-interest of the allies, the Kremlin paid tribute to the grandiose Operation Overlord. Stalin's message to Churchill on June 11 stated that "the history of war knows no other similar enterprise in terms of its scale, broad conception and skill in execution." The exact authorship of this message remains unclear: Molotov’s draft, preserved in Stalin’s archive, does not contain significant Stalinist corrections, but its text almost verbatim coincides with Stalin’s interview with the Pravda newspaper of June 14 and with what Stalin said on the same days to Ambassador A. Harriman39. Perhaps he simply used the Molotov text he liked, but, most likely, the people's commissar sketched it from the words of Stalin himself, especially since Molotov in his correspondence was usually careful not to get into questions of military strategy, leaving them to the "Supreme". Molotov's episodic forays in this direction rarely went uncorrected. For example, in the same June, he sent Stalin a draft notification of the Allies about the second round of the Soviet offensive (Operation Bagration),

prepared by Molotov's eloquent deputy A. Ya. Vyshinsky and slightly "dried" by the people's commissar himself. Comparison of the draft and the final version clearly shows the features of the Stalinist style:

1) “As for our offensive, we are not going to give the Germans a respite, but we will continue to expand the front of our offensive operations, strengthening the power of our onslaught on the German armies, more and more beginning to feel the power of our joint blows. 2) “Regarding our offensive, we can say that we will not give the Germans a break, but will continue to expand the front of our offensive operations, increasing the power of our onslaught on the German armies”40.

Allied harmony, however, did not last long, and the Polish question again became the main irritant. The passions of the parties were especially inflamed in connection with the Warsaw uprising, raised by the Home Army and the London government in early August 1944 without notice Soviet command. Stalin, as you know, refused to support this, in his words, "adventure" and did not spare colors to belittle the role and capabilities of the rebels. In the draft message to Churchill dated August 5, he adds the final passage from himself: “The Polish regional army consists of several detachments, which are incorrectly called divisions. They have no artillery, no aircraft, no tanks. I can't imagine how such detachments can take Warsaw, for the defense of which the Germans put up four tank divisions, including the Hermann Goering division. As the scale of the Warsaw tragedy became clear, Stalin began to show sympathy for its victims, whom a "bunch of criminals" threw "under German guns, tanks and aircraft." But even from this draft message to Churchill of August 22, he erases the words of his deputy, which seemed to him, apparently too emotional, about his readiness to “help our brother Poles liberate Warsaw and avenge the Nazis for their bloody crimes in the capital of the Poles”41. The Polish problem continued to poison allied relations until the very end of the war in Europe.

Thus, in Stalin's big message to Roosevelt on Polish affairs dated December 27, 1944, it was about the connivance of the Mikolajczyk government for the anti-Soviet actions of the Home Army in the rear of the Red Army. To characterize these "underground agents of the Polish government in exile" Stalin adds key words: "terrorists" who kill not only "any

day" (as it was with Molotov), but "soldiers and officers of the Red Army"; "Polish emigrants" in the English capital he turns into "a bunch of Polish emigrants in London." The main signal of the message - the USSR sees the future government of Poland not in London, but in the Polish Committee of National Liberation created under the Soviet auspices. Understanding the need for the most convincing argument for the allies on this key and controversial issue, Stalin adds a chased passage from himself with arguments about the interests of the USSR in Poland, which he will then repeat both in correspondence and at a conference in Yalta: “It should be borne in mind that the Soviet Union is more interested in strengthening pro-Allied and democratic Poland than any other power, not only because the Soviet Union bears the main burden of the struggle for the liberation of Poland, but also because Poland is a state bordering on the Soviet Union and the problem of Poland is inseparable from security problems of the Soviet Union. To this it must be added that the successes of the Red Army in Poland in the fight against the Germans largely depend on the presence of a calm and reliable rear in Poland, and the Polish National Committee fully takes this circumstance into account, while the government in exile and its underground agents, by their terrorist actions, create a threat to civilian life. wars in the rear of the Red Army and oppose the successes of the latter”42.

The toughening resistance of the allies on the issue of the composition of the future governments of Poland and Romania was largely due to domestic political considerations - the pressure of public opinion and the Eastern European diaspora in the United States. Churchill, who back in October

1944 enthusiastically divided the Balkans with Stalin into spheres of influence, now loudly protesting against Soviet violations of the "Declaration on a Liberated Europe" signed in Yalta. Meanwhile, in internal correspondence, the Anglo-Saxons acknowledged the vulnerability of their position. The Yalta Agreement, Roosevelt reminded Churchill in a message of March 29, "places more emphasis on the Lublin Poles than on the other two groups."43 The Prime Minister himself was aware of the inconsistency of the appeal to the democratic principles of self-determination against the backdrop of his secret ("percentage") deal with Stalin. “I really don’t want,” he confessed to Roosevelt in early March, “pedaling this issue to such an extent that Stalin could say,“ I didn’t interfere in your actions in Greece, why don’t you give me such

freedom of hands in Romania?”44. But in Moscow, the protests of the allies were perceived precisely as a manifestation of a double standard - a hypocritical violation of the unwritten rule of non-interference in a "foreign" sphere of influence. “Poland is a big deal! - Molotov wrote in the margins of Vyshinsky's note on the Polish question in February

1945 - But how the governments in Belgium, France, Germany, etc. are organized, we do not know. We were not asked, although we do not say that we like one or the other of these governments. We did not intervene, since this is the zone of operations of the Anglo-American troops” (emphasized in the text - author)45. Later, this cry from the heart of the people's commissar in a softened form will migrate to Stalin's message to Churchill on April 2446.

One of the last dramatic episodes of the "Big Three" correspondence is connected with the well-known "Bern Incident" - the secret contacts of American intelligence with Nazi representatives in Bern in March 1945, which Stalin, not without reason, considered separate negotiations on the surrender of German troops in Northern Italy. Given the main role of the American side in this matter, he concentrated fire on the White House.

The first detailed message to Roosevelt on this issue dated March 29 was prepared by Molotov and left by Stalin almost without amendments. Carefully studying the American response he received, Stalin emphasizes the key passages in it: "there were no negotiations on surrender", "the goal was to establish contact", "Your information ... is erroneous." However, Roosevelt was never able to answer the main question - if the Allies had nothing to hide, then why did they refuse to invite Soviet representatives to Bern? Starting from these points of reference, Stalin counters point by point the president's excuses in his April 3rd message, which he writes entirely himself this time. Before finally approving the text, Stalin decides to sharpen the sound of this already angry document to the utmost. The last two additions are made to the message (marked in italics - author): “It is clear that such a situation cannot serve the cause of maintaining and strengthening trust between our countries ... Personally, and my colleagues, I would in no way take such a risky step, realizing that the momentary benefit, whatever it may be, pales before the fundamental benefit of maintaining and strengthening confidence between the allies.

Stalin's message breathes "suspicion and distrust of our motives," he wrote in

his diary W. Leahy. “I prepared for the president a sharp reply, which was then sent to Marshal Stalin, as close to a rebuke as possible in diplomatic exchanges between states.”48 Churchill expressed his solidarity with the President in a message to Stalin dated 5 April. However, in the end, the Kremlin's harsh rebuff had its effect: the incident was soon settled and Roosevelt, overcoming the objections of his "hawks", preferred to end this heavy explanation on a conciliatory note. On April 12, a few hours before his death, he wrote to Stalin: “Thank you for your sincere explanation of the Soviet point of view regarding the Bern incident, which, as it now seems, has faded and receded into the past, without bringing any benefit. In any case, there should be no mutual distrust, and minor misunderstandings of this nature should not arise in the future. Ambassador Harriman, who had a hand in fueling this crisis, delayed the transmission of this message, suggesting that the term "minor" be deleted from it, but Roosevelt considered this nuance very important. "I have no intention," he promptly replied to Harriman, "to omit the word 'insignificant', for I wish to regard the Bernese misunderstanding as an insignificant incident." In his last message to Churchill on April 11 (one of the very few written in his own hand), Roosevelt also spoke in favor of "minimizing the Soviet problem", since the existing differences "arise and are settled almost daily, as in the case of the meeting in Bern"51.

Roosevelt's death removed the last leash on Churchill's growing anti-Sovietism. The last weeks of the war and the victorious May were marked by a whole series of his open and secret steps aimed at limiting Soviet influence in Europe - starting from attempts to draw the Americans into the battle for Berlin and delaying his troops in the zone of occupation of Germany assigned to the Red Army and ending with the development of a plan for war with USSR (Operation Unthinkable)52. Churchill's "spring aggravation" penetrated into his contacts with the Soviet side, including correspondence with Stalin, in which he, taking advantage of G. Truman's inexperience, assumes the role of the main representative of the allies. On April 28, Churchill (who shortly before had sent an alarmist telegram to Truman about an "Iron Curtain" in Europe) sent a long message to Stalin detailing all the post-Yalta claims of the Allies. Message from the veins

It began with what Churchill himself called “an outpouring of my soul to you” - a heartfelt warning about the threat of a post-war split into the Soviet and Anglo-American world: “It is quite obvious that a quarrel between them would tear the world apart and that all of us, the leaders of each of parties who had to have anything to do with it would be shamed before history”53. Churchill's outpouring remained unanswered - Stalin ignored its general part, limiting himself to continuing the polemic on the Polish question.

Meanwhile, he was well informed about the mood and intrigues of the prime minister, including the "Unthinkable", as well as the preservation of German captured weapons and military units for possible use against the USSR. All this only strengthened Stalin in his attitude towards Churchill as the main and incorrigible potential adversary, with whom it was useless to conduct a strategic dialogue. It is no coincidence, apparently, sensing this mood of the "Master", Ambassador Gusev in his dispatches begins to warn "that we are dealing with an adventurer for whom war is his native element, that in war conditions he feels much better than in peace conditions." time"54. Truman did not inspire much hope, as he began to move away from the policy of his predecessor. “Now, after the death of President Roosevelt,

Stalin told GK Zhukov and Molotov, “Churchill will quickly clash with Truman”55. Further correspondence with Western partners became more and more dry and purely official. At the final stage, Stalin less and less intervenes in the texts prepared by Molotov. The correspondence of the allies was coming to an end - like the union itself.

Vladimir O. Pechatnov. Stalin-Roosevelt-Churchill: the Big Three through the wartime correspondence

The article based on new documents from the Russian State Archive of Social-Political History and the Archive of Foreign Policy of Russia sheds a new light on Stalin's correspondence with Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill during World War II. The author examines how those messages were actually written and what was Stalin's personal contribution to the correspondence. Based on his editing of Vyacheslav M. Molotov's drafts revealed are Stalin's motives and priorities on such issues as opening of the second front, lend-lease, the Polish question, and WWII summits of "The Big Three". Also examined is Stalin's differential treatment of Roosevelt and Churchill. Newly declassified dispatches of Soviet Ambassador in London Ivan M. Maisky provide a vivid description of Churchill's immediate reaction to Stalin's messages. The article demonstrates the opportunities for further exploration of the Big Three correspondence as a major source on the Allied diplomacy during WWII.

1. Churchill & Roosevelt. The Complete Correspondence. Edited With Commentary by W. Kimball. Vol. 1-3. Princeton, 1984.

2. Pechatnov V. O. How Stalin wrote to Roosevelt (according to new documents). / / Source, 1999. No. 6; Idem. Stalin and Roosevelt (notes

historian). / War and society, 1941-1945: In 2 books. /Answer. ed. G. N. Sevostyanov. M., 2004. Book. one.

3. See: Churchill & Roosevelt. Vol. 1. P. 32.

4. This reputation of Churchill was well known in the Roosevelt White House. Forwarding to her husband one of Churchill's most outspoken statements against Bolshevism during the Civil War, Eleanor Roosevelt attributed: "It is not surprising if Mr. Stalin cannot forget it in any way" (Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, President "s Secretary File, Great Britain, W. Churchill ).

5. Staff meeting. December 8,1943. Library of Congress, W. A. Harriman Papers, Chronological File. cont. 171.

6. For more details, see: Pechatnov V. O. Stalin and Roosevelt (historian's notes). pp. 402-403.

7. Churchill & Roosevelt. Vol. 1. P. 529-533.

8. Ibid. P. 545.

9. Rzheshevsky O. A. Stalin and Churchill. Meetings. Conversations. Discussions: Documents, comments, 1941-1945. M., 2004.

10. Churchill & Roosevelt. Vol. 1. P. 570-571.

11. Rzheshevsky O. A. Stalin and Churchill. pp. 376, 378.

12. Russian State Archive of Socio-Political History (hereinafter - RGASPI). F. 558. D. 256. L. 154. Equally positively, Stalin assessed the deal with Darlan in a message to Roosevelt dated December 14 // Correspondence of the Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR with the US presidents and British prime ministers during the Great Patriotic War of 1941-1945 M., 1957, (hereinafter - Correspondence ...). T. 2. P. 43.

13. Ibid.

15. Correspondence... T. 2. S. 40-41.

16. WUA RF. F. 059a. Op. 7. P. 13. D. 6. L. 221-222. The same dispatch from Maisky contains Churchill’s remark, unusual for an inveterate anti-Soviet, made under the fresh impression of the defeat of the Germans at Stalingrad: “Churchill is completely delighted and even touched by the Red Army. When he talks about her, tears come to his eyes. Comparing Ros-

This last war and Russia (that is, the USSR) of the current war, Churchill said: "Taking into account all factors, I believe that the new Russia is five times stronger than the old." Slightly teasing Churchill, I half-laughing asked: “And how do you explain this phenomenon?” Churchill answered me in the same tone: “If your system brings happiness to the people, I am for your system. However, I am little interested in what will happen after the war ... Socialism, communism, cataclysm ... if only the Huns were defeated. (Ibid. L. 224).

17. Churchill & Roosevelt. Vol. 2. P. 43.

18. RGASPI. F. 558. D. 260. L. 62.

19. Churchill & Roosevelt. Vol. 2. P. 175-177.

20. WUA RF. F. 059a. Op. 7. P. 13. D. 6. L. 259-260.

21. Correspondence ... T. i. C. ill.

22. Churchill & Roosevelt. Vol. 2. P. 179.

24. Correspondence...T. i. S. 138.

25. WUA RF. F. 059a. Op. 7. P. 13. D. 6. L. 295-296.

26. AP RF. F. 45. Op. i. D. 366. L. 22.

27. Ibid. L. 71.

28. RGASPI. F. 558. D. 264. L. 38.

29. Churchill & Roosevelt. Vol. 2. P. 536.

30. AP RF. F. 45. Op. i. D. 367. L. 44.

31. There.L.55.

32. RGASPI. F. 558. D. 265. L. 89.

33. RGASPI. F. 558. D. 267. L. 44; Correspondence ... T. i. S. 215.

34. Churchill & Roosevelt. Vol. 3. P. 69-74.

35. Correspondence...T. i. S. 228.

36. Churchill & Roosevelt. Vol. 3. P. 173.

38. Narinsky M. M. Stalin and M. Thorez. 1944-1947. New materials. / Modern and Contemporary History, 1996. No. i. S. 28.

40. RGASPI. F. 558. D. 267. L. 176.

41. RGASPI. F. 558. D. 268. L. 116.158.

42. AP RF. F. 45. Op. i. D. 369. L. 110,117.

43. Churchill & Roosevelt. Vol. 3. P. 593.

44. Ibid. P. 547.

45. WUA RF. F. 06. Op. 7. D. 588. L. 2.

46. Correspondence...T. i. S. 335.

47. AP RF. F. 45. Op. i. D. 370. L. 98-100.

48. Leahy Diaries, April 4, 1945. National Archives, Record Group 218, William Leahy Records, 1942-1948. cont. 4.

49. Correspondence...T. 2. S. 211-212.

50. For Harriman from the President, April 12,1945. Library of Congress, W. A. Harriman Papers, Chronological File. cont. 178.

51. Churchill & Roosevelt. Vol. 3. P. 630.

52. Sokolov VV Stalin and Churchill - friends and allies involuntarily // War and society, 1941-1945. Book. i. pp. 445-446; Rzhe-

Shevsky O. A. Secret military plans of W. Churchill in May 1945 // New and Contemporary History, 1999. No. 3.

53. Correspondence ... T. i. S. 349.

54. WUA RF. F. 059a. Op. 7. P. 13. D. 6. L. 357-358.

55. Zhukov GK Memories and reflections. M., 1969. S. 713.

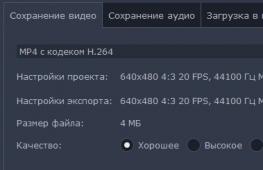

Winter 1945, Yalta. High-level meeting of leaders of countries is being prepared anti-Hitler coalition. Allied intelligence agencies are developing a plan to protect Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill. And not in vain: it became known that a terrorist attack was planned in the city. Watch on May 7 at 17.15 on the TV channel "MIR" the film "Yalta-45".

Do you know what the operation to ensure the safety of the leaders of the Big Three was called, why Roosevelt's bathtub was repainted seven times, and why Churchill went to Sevastopol after the conference? About these and other little-known details historical events 1945 in the Crimea - in the material "MIR 24".

The Yalta conference of the "Big Three" - the leaders of the USSR, Great Britain and the USA - played a colossal role in the history of the post-war world order. Second World War was actually coming to an end, and the focus of attention of the leaders of the three leading world powers of that time was on the issues of the post-war division of the world. It was at the Yalta Conference that such important issues as the borders of Poland and the Soviet Union and the creation of independent states in the Balkans, the boundaries of the zones of occupation of Germany and measures for its maximum weakening, the conditions for the entry of the USSR into the war with Japan and the fate of prisoners of war and displaced persons were resolved.

Unlike the Tehran conference of 1943, at which all three countries played approximately the same role, the Yalta conference became the actual triumph of the Soviet Union. Start at least from the venue of the high meeting. Initially, the heads of the United States and Great Britain offered to meet in Scotland, a place equidistant from both American and Soviet shores. Stalin abandoned the Scottish plan - as the legend goes, because he did not want to go to "men in skirts." In fact, the Soviet leader was well aware that it was his country, whose army was already standing a hundred kilometers from Berlin, that had the right to dictate its terms.

He did everything so that the American and British leaders saw with their own eyes the catastrophic destruction to which the Germans subjected Soviet cities and villages. This gave Stalin a significant trump card in the negotiations on reparations - and as time has shown, this was the right step. After Scotland, Rome, Alexandria, Jerusalem, Athens and even Malta were proposed as a meeting place - for the same reasons, but all these ideas were rejected by Moscow in favor of the Crimea. And the allies made concessions.

It took only two months for the Soviet Union to organize a meeting in Yalta - despite the fact that Crimea was just as devastated as all the other occupied territories of the USSR. The operation to hold the meeting, initiated by Winston Churchill, received two code names. “Argonauts”, since the British Prime Minister compared himself and the US President with Argonauts sailing to the shores of Crimea for a new Golden Fleece. And "Island" - for the purposes of conspiracy, with a hint of Malta.

In 60 days, several hundred workers from all over the country, led by NKVD and NKGB officers, as well as operatives, counterintelligence officers and the military, managed to do everything to make the Yalta Conference not only possible, but also demonstrate the capabilities of the USSR for post-war reconstruction. And the desired effect was achieved!

How Marshal Stalin showed who was in charge in Yalta

Both British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and American President Franklin Roosevelt viewed the meeting in Yalta as an opportunity, above all, to get Soviet leader Joseph Stalin to make concessions on the issue of military support for the operations of US and British troops in Germany. By February 1945, it was the Red Army that achieved the most impressive results, approaching almost Berlin itself, while the Allies were much further and experienced great difficulties.

The allies also understood that by agreeing to a meeting in Yalta, they put themselves in the position of invited guests, who largely depend on the owner. To emphasize this, Marshal Stalin at first did not go to meet the distinguished guests arriving at the airfield in the city of Saki, and when Roosevelt, who himself was dissatisfied with such a violation of protocol, and at the request of Churchill expressed his displeasure to the Soviet leader, he made it clear that a long delay with the opening of the second front and the unconditional leadership of the USSR in advancing to Berlin and defeating Germany give him such a right. By the way, Stalin pointedly was late for the first official meeting of the three on February 4 - the only time in the entire Yalta Conference. And the allies also understood this hint correctly.

The plundered Crimean palaces were refurbished

Photo: wikipedia.org / public domain

The two-year occupation of the Crimea by German troops cost the peninsula dearly - including in the most direct sense. When Yalta had already been chosen as the meeting place, and inspection trips to the Crimean palaces began, it turned out that these palaces had been stripped down to their bare walls by the Nazis in the full sense of the word. In particular, in the Livadia Palace, which was supposed to become the main place of negotiations, there were not even fabric wallpapers on the walls and copper handles on the doors - everything was taken out by "supermen" in German uniforms. Therefore, the situation in the Livadia, Yusupov and Vorontsov palaces had to be collected literally from the pine forest - from all over the Soviet Union. As one of the eyewitnesses of those events recalled, furniture and furnishings, carpets and rugs, kitchen utensils and expensive sets were transported from Moscow to the Crimea by echelons.

What is Operation Valley

Under this code name, an operation was carried out to ensure the accommodation and security of the participants in the Yalta Conference. To restore the destroyed palaces, repair the Crimean roads leading to Yalta from the Saki airfield (Roosevelt and Churchill's planes landed there) and Simferopol (Stalin came there by train from Moscow), as well as to solve other everyday issues, about 2,500 workers were involved, half of which immediately "threw" to Livadia. About a thousand only operatives of the NKVD and the NKGB of the Crimean ASSR took part in security measures, not counting the units of the troops for the protection of the rear and other military units. Within two weeks, not a single German prisoner of war remained near the conference venue, and at the end of January, within a radius of 30 km from the Livadia Palace, the entire local population was evicted.

During the month, 287 operational measures were carried out on the South Bank, checking more than 67 thousand people and detaining almost 400, as well as confiscating 267 rifles, 1 machine gun, 43 machine guns, 49 pistols, 283 grenades and 4186 cartridges. In addition, by the beginning of the conference in the Black Sea off the coast of Yalta, a triple ring of warships was built, about 300 combat aircraft were involved, and the meeting place was covered on land by two round-the-clock security rings, to which a third was added at night.

How the Livadia Palace became the main meeting place for the Big Three

Photo: wikipedia.org / public domain

Although there are enough palaces in the Crimea, including those in the vicinity of Yalta, only three of them were preparing for the conference. The Soviet delegation was stationed in Yusupovsky, the British delegation in Vorontsovsky in Alupka, and the Americans were taken to Livadia. And although diplomatic protocol requires that the place of negotiations be neutral territory, all the main events of the conference were planned from the very beginning to be held "at home" at US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

This was due primarily to the fact that the American president moved exclusively in a wheelchair, suffering from a long-standing illness with polio. Organization of Roosevelt's constant moving would take additional time and would have a bad effect on his well-being, which also contradicted the diplomatic protocol. As a result, they decided to choose the lesser of the two violations and meet where it was convenient for the US leader.

How Roosevelt's bathroom was repainted seven times

Photo: wikipedia.org / public domain

Documentary evidence of this fact did not remain, however, eyewitnesses to the events of January 1945 spoke confidently about it. At the last stage of preparations for the conference, British and American specialists participated in fine-tuning the premises reserved for the leaders of the Big Three.

The US inspectors felt that the paint color chosen by the Soviet workers, which covered the walls of the bathroom near Franklin Roosevelt's apartment, did not go well with the view of the Black Sea. As a result, to achieve the desired shade, the bathroom was repainted seven times. And apparently, they still managed to please the tastes of the most famous US leader of the twentieth century. Going home, Roosevelt shared with Stalin his plans after his resignation to buy out the Livadia Palace and settle in it in retirement.

Why was Winston Churchill the last to leave Crimea?

Photo: wikipedia.org / public domain

Joseph Stalin and Franklin Roosevelt left Yalta at the same time - the day after the end of the Yalta Conference. The leader of the USSR reached Simferopol by car and from there went to Moscow by train, and on February 12, the US president took off from the Saki airfield on a C-45 plane and, accompanied by six fighters, went to Cairo.

But the British prime minister stayed in Crimea for another two days, having managed to get to Sevastopol. The reason for this was the visit of Winston Churchill to Balaklava, more precisely, to the Alma Valley, where in the middle of autumn 1854 the attack of the British light cavalry cost the lives of representatives of many aristocratic families of Great Britain. Among them were the Dukes of Marlborough, the ancestors of Winston Churchill. And the promise to organize a visit to Balaklava was one of the arguments in favor of holding a conference in Yalta.

How Stalin had only one interpreter left before the conference

Photo: wikipedia.org / public domain

Throughout the Great Patriotic War at international meetings, Joseph Stalin was assisted by two translators - Vladimir Pavlov and Valentin Berezhkov. During Operation Valley, Soviet counterintelligence also checked all the participants in the future meeting, not excluding translators. It was during this check that the fact was revealed that the parents of the translator Berezhkov remained in the occupied territory - in Kiev.

But the matter was not limited to this: despite all the efforts of Valentin Berezhkov himself to find his relatives, he did not achieve success, from which the counterintelligence officers concluded that his parents could leave the city along with the retreating Germans (much later it turned out that they had left the city back in 1943). This was enough to remove the translator from participation in the conference, and only Vladimir Pavlov went to Yalta with Stalin.

LEARN ZEN WITH NOW READ US IN YANDEX. NEWS

2. Hanging the flags of the USSR, USA and Great Britain before the start of the Yalta Conference.

3. Saki airfield near Simferopol. V.M. Molotov and A.Ya. Vyshinsky met the plane of British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

4. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who arrived at the Yalta Conference, at the gangway.

5. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who arrived at the Yalta Conference, at the airport.

6. British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who arrived at the Yalta Conference, at the airport.

7. Passage on the airfield: V.M. Molotov, W. Churchill, E. Stettinius. In the background: translator V.N. Pavlov, F.T. Gusev, Admiral N.G. Kuznetsov and others.

8. Livadia Palace, where the Yalta Conference was held.

9. Meeting at the airport, US President FD Roosevelt, who arrived at the Yalta Conference.

10. F.D. Roosevelt and W. Churchill.

11. Meeting at the airport, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who arrived at the Crimean Conference. Among those present: N.G. Kuznetsov, V.M. Molotov, A.A. Gromyko, W. Churchill and others.

12. Stettinius, V.M. Molotov, W. Churchill and F. Roosevelt at the Saki airfield.

13. Arrival of US President F. Roosevelt. V.M. Molotov talks with F. Roosevelt. Present: A.Ya. Vyshinsky, E. Stettinius, W. Churchill and others.

14. Conversation of the US Secretary of State E. Stettinius with the People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the USSR V. M. Molotov.

15. Conversation V.M. Molotov with General J. Marshall. Present: translator V.N. Pavlov, F.T. Gusev, A.Ya. Vyshinsky and others.

16. Meeting at the airport, US President FD Roosevelt, who arrived at the Yalta Conference. Among those present: V.M.Molotov, W.Churchill, A.A.Gromyko (from left to right) and others.

17. Review of the guard of honor: V.M. Molotov, W. Churchill, F. Roosevelt and others.

18. Passage of the guard of honor in front of the participants of the Crimean Conference: US President F. Roosevelt, British Prime Minister W. Churchill, People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the USSR V. Molotov, US Secretary of State E. Stettinius, Deputy. People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs A.Ya. Vyshinsky and others.

19. V. M. Molotov and E. Stettenius are sent to the meeting room.

20. Before the meeting of the Crimean Conference. People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs V.M. Molotov, Foreign Minister A. Eden and US Secretary of State E. Stettinius in the Livadia Palace.

21. British Prime Minister W. Churchill and US Secretary of State E. Stettinius.

22. Head of the Soviet government I.V. Stalin and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill in the palace during the Yalta Conference.

23. British Prime Minister W. Churchill.

24. Military advisers of the USSR at the Yalta Conference. In the center - General of the Army AI Antonov (1st Deputy Chief of the General Staff of the Red Army). From left to right: Admiral S.G. Kucherov (Chief of Staff of the Navy), Admiral of the Fleet N.G. Kuznetsov (Commander-in-Chief of the Navy), Air Marshals S.A. Khudyakov (Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Air Force) and F.Ya. ).

25. Daughter of British Prime Minister W. Churchill, Mrs. Oliver (left) and daughter of US President F.D. Roosevelt Ms. Bettiger in the Livadia Palace during the Yalta Conference.

26. Conversation of I.V. Stalin with W. Churchill. Present: V.M.Molotov, A.Eden.

27. Yalta Conference 1945 Meeting of Foreign Ministers. Livadia Palace. Present: V.M. Molotov, A.A. Gromyko, A. Eden, E. Stettinius.

28. W. Churchill's conversation with I.V. Stalin in the gallery of the Livadia Palace.

29. Signing of the protocol of the Yalta Conference. At the table (from left to right): E. Stettinius, V. M. Molotov and A. Eden.

30. People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the USSR V.M. Molotov signs the documents of the Yalta Conference. On the left, US Secretary of State E. Stettinius.

31. Marshal of the Soviet Union, Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR and Chairman of the State Defense Committee of the USSR Iosif Vissarionovich Stalin, US President Franklin Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill at the negotiating table at the Yalta conference.

In the photo, he sits to the right of I.V. Stalin's deputy People's Commissar Foreign Affairs of the USSR Ivan Mikhailovich Maisky, second to the right of I.V. Stalin - USSR Ambassador to the United States Andrei Andreyevich Gromyko, first from the left - People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the USSR Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov (1890-1986), second from the left - First Deputy People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the USSR Andrei Yanuarievich Vyshinsky (1883-1954). To the right of Winston Churchill sits British Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden. Sits on the right hand of F.D. Roosevelt (pictured to the left of Roosevelt) - US Secretary of State - Edward Reilly Stettinius. Sits second to the right of F.D. Roosevelt (pictured second to the left of Roosevelt) - Chief of Staff of the President of the United States - Admiral William Daniel Lehi (Lehi).

32. W. Churchill and E. Eden enter the Livadia Palace in Yalta.

33. US President Franklin Roosevelt (Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1882-1945) talking with the People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the USSR Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov (1890-1986) at the Saki airfield near Yalta.In the background, third from left, Admiral of the Fleet Nikolai Gerasimovich Kuznetsov (1904-1974), People's Commissar of the Navy of the USSR.

34. Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin at the Yalta Conference.

35. People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the USSR Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov (1890-1986) shakes hands with US presidential adviser Harry Hopkins (Harry Lloyd Hopkins, 1890-1946) at the Saki airfield before the start of the Yalta conference.

36. Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin at the Yalta Conference.

37. Marshal of the Soviet Union, Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR and Chairman of the State Defense Committee of the USSR Iosif Vissarionovich Stalin, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill (Winston Churchill, 1874-1965) and US President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) at a banquet during Yalta conference.

38. V.M. Molotov, W. Churchill and F. Roosevelt greet Soviet soldiers at the airfield in Saki.

39. I.V. Stalin in talks with US President F. Roosevelt during the Yalta Conference.

40. I.V. Stalin leaves the Livadia Palace during the Yalta Conference. Right behind I.V. Stalin - First Deputy Head of the 6th Directorate of the People's Commissariat of State Security of the USSR, Lieutenant General Nikolai Sidorovich Vlasik (1896-1967).

41. V.M. Molotov, W. Churchill and F. Roosevelt are bypassing the formation of Soviet soldiers at the Saki airfield.

42. Soviet, American and British diplomats during the Yalta Conference.

In the photo, 2nd from the left - First Deputy People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the USSR Andrei Yanuarievich Vyshinsky (1883-1954), 4th from the left - US Ambassador to the USSR Averell Harriman (William Averell Harriman, 1891-1986), 5th from the left - People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the USSR Vyacheslav Mikhailovich Molotov (1890-1986), 6th left - British Foreign Minister Anthony Eden (Robert Anthony Eden, 1897-1977), 7th left - US Secretary of State Edward Stettinius (Edward Reilly Stettinius, 1900-1949 ), 8th from left - British Deputy Foreign Secretary Alexander Cadogan (Alexander George Montagu Cadogan, 1884-1968).

Preparations for the Yalta Conference, which lasted from February 4 to February 11, 1945, began at the end of 1944. It (preparation) involved not only the leaders of the anti-Hitler "Big Three", but also their closest advisers, assistants, foreign ministers. Among the main participants on our side, one can naturally name Stalin himself, Molotov, as well as Vyshinsky, Maisky, Gromyko, Berezhkov. The latter, by the way, left very interesting memoirs that came out during his lifetime and were republished after his death.

Thus, by the time all three members of the anti-Hitler coalition gathered in Yalta, the agenda had already been agreed and some positions had been clarified. That is, Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt arrived in Crimea with an understanding of what issues their positions more or less coincide with, and on which they still have to argue.

The venue for the conference was not chosen immediately. Initially it was proposed to hold the meeting in Malta. Even such an expression appeared: “from Malta to Yalta”. But in the end, Stalin, referring to the need to be in the country, insisted on Yalta. Hand on heart, we must admit that the "father of nations" was afraid to fly. History has not preserved a single flight of Stalin on an airplane.

Among the issues to be discussed in Yalta, three were the main ones. Although, no doubt, a much wider range of problems was touched upon at the conference, and agreements were reached on many positions. But the main ones, of course, were: the UN, Poland and Germany. These three questions robbed the Big Three leaders of most of their time. And on them, in principle, agreements were reached, although, to be honest, with great difficulty (especially on Poland).

Diplomats during the Yalta Conference. (pinterest.com)

With regard to Greece, we had no objections - the influence remained with Great Britain, but Stalin rested on Poland: he did not want to give it away, referring to the fact that the country borders on the USSR and it was through it that the war came to us (and not for the first time, By the way, in history we were threatened from there). Therefore, Stalin had a very firm position. However, despite Churchill's categorical resistance and unwillingness to meet halfway, the Soviet leader got his way.

What other options for Poland did the allies have? In those days there (in Poland) there were two governments: Lublin and Mikolajczyk in London. On the latter, of course, Churchill insisted and tried to win Roosevelt over to his side. But the American president made it very clear to the British prime minister that he did not intend to spoil relations with Stalin on this issue. Why? The explanation was simple: there was still a war with Japan, which was not of particular interest to Churchill, and Roosevelt did not want to bicker with the Soviet leader in anticipation of a future alliance to defeat Japan.

As already mentioned, preparations for the conference began at the end of 1944, almost immediately after the opening of the Second Front. The war was drawing to a close, it was clear to everyone that Nazi Germany would not last long. Consequently, it was necessary to decide, firstly, the question of the future and, secondly, to divide Germany. Of course, after Yalta there was also Potsdam, but it was in Crimea that the idea (it belonged to Stalin) appeared to give the zone to France (for which, we note, de Gaulle was always grateful to the USSR).

Also in Livadia, a decision was made to grant UN membership to Belarus and Ukraine. At first, the conversation was about all the republics of the USSR, Stalin gently insisted on this for some time. Then he abandoned this idea and named only three republics: Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania (subsequently very easily abandoning the latter). Thus, two republics remained. To smooth the impression and soften his persistence, the leader of the Soviet state suggested that the Americans also include two or three states in the UN. Roosevelt did not go into this business, foreseeing, most likely, complications in Congress. Moreover, it is interesting that Stalin had a rather convincing reference: India, Australia, New Zealand- all this is the British Empire, that is, the UK will have plenty of votes in the UN - the chances need to be equalized. Therefore, the idea of additional votes of the USSR arose.

Stalin in negotiations with Roosevelt. (pinterest.com)

Compared with Poland, the discussion of the "German Question" did not take long. They talked about reparations, in particular, about the use of the labor of German prisoners of war to pay off all the damage caused by the German army during the occupation of Soviet territory. Other issues were also discussed, but there were no objections from our allies, Britain or the United States. Apparently, all the energy was focused on discussing the future of Poland.

An interesting detail: when the participants (in this case we are talking about Great Britain and the USSR) were distributing zones of influence in Europe, when Stalin agreed to leave Greece to Great Britain, but did not agree to Poland in any way, our troops were already in Hungary and Bulgaria. Churchill sketched a distribution on a piece of paper: 90% of Soviet influence in Poland, 90% of British influence in Greece, Hungary or Romania (one of these countries) and Yugoslavia - 50% each. Having written this on a piece of paper, the British Prime Minister pushed the note to Stalin. He looked, and, according to the memoirs of Berezhkov, Stalin's personal translator, "flicked it back to Churchill." Say, there are no objections. According to Churchill himself, Stalin ticked the document, right in the middle, and pushed it back to Churchill. He asked: "Shall we burn the paper?" Stalin: "As you wish. You can keep it." Churchill folded this note, put it in his pocket and then showed it. True, the British minister did not fail to remark: "How quickly and not very decently we decide the future of the countries of Europe."

The "Iranian issue" was also touched upon at the Yalta Conference. In particular, he was associated with Iranian Azerbaijan. We were going to create another republic, but the allies, the United States and Great Britain, simply reared up and forced us to abandon this idea.

The leaders of the big three at the negotiating table. (pinterest.com)

Now let's talk about the main participants of the conference. Let's start with Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Prior to the meeting in Yalta, the US president's personal physician, Dr. Howard Bruen, examined Roosevelt to understand his physical condition: whether he could bear the flight, and indeed the conference itself. The president's heart and lungs were found to be fine. True, things were worse with pressure - 211 to 113, which, probably, should have alerted. But Roosevelt had an enviable character trait: he knew how to get ready. And the president gathered himself, showing extraordinary energy, joking, ironic, quickly reacting to all the questions that arose, and thereby somewhat reassured his relatives and advisers that everything was in order. But the pallor, yellowness, blue lips - all this attracted attention and gave Roosevelt's critics grounds to assert that, in fact, the physical condition of the American president explains all his inexplicable concessions to Stalin.

Roosevelt's closest advisers, who nevertheless were by his side and bore a certain degree of responsibility for the agreements that were reached, argued that the president was in complete control of himself, was aware of everything he spoke about, agreed to and went to. “I have succeeded in everything I could succeed in,” Roosevelt said after Yalta in Washington. But this by no means removed the charges from him.

When Franklin Delano Roosevelt returned home, he spent all his time at the Warm Springs residence. And on April 12, almost exactly two months after the end of the Yalta meeting, Roosevelt, signing government documents, while the artist Elizaveta Shumatova, invited by a friend of the president, Mrs. Lucy Rutherfurd, was painting his portrait, suddenly raised her hand to the back of her head and said: “ I have a terrible headache." These were the last words in the life of Franklin Roosevelt.

It is worth noting that on the eve of April 12, the American president sent his last telegram to Stalin. The fact is that the Soviet leader received information about the meetings of Allen Dulles, OSS resident in Bern, with General Wolf. Stalin, having learned about this, did not fail to turn to Roosevelt with such, one might say, not quite an ordinary letter, expressing protest, even amazement, surprise. How so? We are such friends, we are frank all the time in a relationship, but here you let me down? Roosevelt reacted. Firstly, he said that he was not conducting any negotiations, that this was a continuation of what had already been started with Stalin's consent. But after all, the USSR was not invited to these negotiations, which is why the Soviet leader was indignant. And Roosevelt wrote to Stalin that he really did not want such an insignificant event to spoil their relationship. And he sent this telegram to Harriman, the US ambassador to the USSR.