Osip Mandelstam - biography, photos, poems, personal life of the poet. Brief biography of Mandelstam Osip Mandelstam biography

One of the most tragic fates was prepared by the Soviet government for such a great poet as O. Mandelstam. His biography developed this way largely due to the irreconcilable character of Osip Emilievich. He could not tolerate lies and did not want to bow to the powers that be. Therefore, his fate could not have worked out differently in those years, which Mandelstam himself was aware of. His biography, like the work of the great poet, teaches us a lot...

The future poet was born in Warsaw on January 3, 1891. Osip Mandelstam spent his childhood and youth in St. Petersburg. His autobiography, unfortunately, was not written by him. However, his memories formed the basis of the book “The Sound of Time.” It can be considered largely autobiographical. Let us note that Mandelstam’s memories of childhood and youth are strict and restrained - he avoided revealing himself, did not like to comment on either his poems or his life. Osip Emilievich was a poet who matured early, or rather, who saw the light. Strictness and seriousness distinguish his artistic style.

We believe that the life and work of such a poet as Mandelstam should be examined in detail. A short biography of this person is hardly appropriate. The personality of Osip Emilievich is very interesting, and his work deserves the most careful study. As time has shown, one of the greatest Russian poets of the 20th century was Mandelstam. The short biography presented in school textbooks is clearly insufficient for a deep understanding of his life and work.

The origin of the future poet

Rather, the little that can be found in Mandelstam’s memories of his childhood and the atmosphere that surrounded him is painted in gloomy tones. According to the poet, his family was “difficult and confusing.” In words, in speech, this was manifested with particular force. So, at least, Mandelstam himself believed. The family was unique. Let us note that the Mandelstam Jewish family was ancient. Since the 8th century, since the time of the Jewish enlightenment, he has given the world famous doctors, physicists, rabbis, literary historians and Bible translators.

Emilius Veniaminovich Mandelstam, Osip’s father, was a businessman and self-taught. He was completely devoid of any sense of language. Mandelstam in his book “The Noise of Time” noted that he had absolutely no language, there was only “languagelessness” and “tongue-tiedness.” The speech of Flora Osipovna, the mother of the future poet and music teacher, was different. Mandelstam noted that her vocabulary was “compressed” and “poor”, the phrases were monotonous, but it was ringing and clear, “great Russian speech.” It was from his mother that Osip inherited, along with musicality and a predisposition to heart disease, accuracy of speech and a heightened sense of his native language.

Training at Tenishevsky Commercial School

Mandelstam studied at the Tenishevsky Commercial School from 1900 to 1907. It was considered one of the best among private educational institutions in our country. At one time, V. Zhirmunsky and V. Nabokov studied there. The atmosphere that reigned here was intellectual-ascetic. The ideals of civic duty and political freedom were cultivated in this educational institution. In the 1905-1907 years of the first Russian revolution, Mandelstam could not help but fall into political radicalism. His biography is generally closely connected with the events of the era. The catastrophe of the war with Japan and the revolutionary times inspired him to create his first poetic experiments, which can be considered student. Mandelstam perceived what was happening as a vigorous universal metamorphosis, renewing the elements.

Travel abroad

He received his college diploma on May 15, 1907. After this, the poet tried to join the military organization of the Social Revolutionaries in Finland, but due to his youth he was not accepted there. Parents, concerned about the future of their son, hastened to send him out of harm’s way to study abroad, where Mandelstam traveled three times. The first time he lived in Paris was from October 1907 to the summer of 1908. Then the future poet went to Germany, where he studied Romance philology at the University of Heidelberg (from the fall of 1909 to the spring of 1910). From July 21, 1910 until mid-October, he lived in Zehlendorf, a suburb of Berlin. Right up to his very last works, Mandelstam’s poems echo his acquaintance with Western Europe.

Meeting with A. Akhmatova and N. Gumilev, creation of Acmeism

The meeting with Anna Akhmatova and Nikolai Gumilyov determined the development of Osip Emilievich as a poet. Gumilyov returned from the Abyssinian expedition to St. Petersburg in 1911. Soon the three of them began to see each other often at literary evenings. Many years after the tragic event - the execution of Gumilyov in 1921 - Osip Emilievich wrote to Akhmatova that only Nikolai Gumilyov managed to understand his poems, and that he still talks to him and conducts dialogues. The way Mandelstam treated Akhmatova is evidenced by his phrase: “I am a contemporary of Akhmatova.” Only Osip Mandelstam (his photo with Anna Andreevna is presented above) could publicly say this during the Stalinist regime, when Akhmatova was a disgraced poetess.

All three (Mandelshtam, Akhmatova and Gumilyov) became the creators of Acmeism and the most prominent representatives of this new movement in literature. Biographers note that friction arose between them at first, since Mandelstam was hot-tempered, Gumilyov was despotic, and Akhmatova was capricious.

First collection of poems

In 1913, Mandelstam created his first collection of poems. By this time, his biography and work had already been marked by many important events, and even then there was more than enough life experience. The poet published this collection at his own expense. At first he wanted to call his book “Sink”, but then he chose a different title - “Stone”, which was quite in the spirit of Acmeism. Its representatives wanted to open the world anew, to give everything a courageous and clear name, devoid of a vague and elegiac flair, like, for example, the Symbolists. Stone is a solid and durable natural material, eternal in the hands of a master. For Osip Emilievich, it is the primary building material of spiritual culture, and not just material.

Osip Mandelstam converted to Christianity back in 1911, making a “transition to European culture.” And although he was baptized in (in Vyborg on May 14), the poems of his first collection captured his passion for the Catholic theme. Mandelstam was captivated by the pathos of the universal organizing idea in Roman Catholicism. Under the rule of Rome, the unity of the Christian world of the West is born from a chorus of peoples dissimilar from each other. Also, the “stronghold” of the cathedral is made up of stones, their “evil heaviness” and “spontaneous labyrinth”.

Attitude to the revolution

In the period from 1911 to 1917, Mandelstam studied at St. Petersburg University, in the Romano-Germanic department. His biography at this time was marked by the appearance of the first collection. His attitude towards the revolution that began in 1917 was complex. Any attempts by Osip Emilievich to find a place for himself in the new Russia ended in scandal and failure.

Compilation Tristia

Mandelstam's poems from the period of revolution and war make up the new collection Tristia. This “book of sorrows” was published for the first time in 1922 without the participation of the author, and then, in 1923, under the title “The Second Book” it was republished in Moscow. It is cemented by the theme of time, the flow of history, which is directed towards its destruction. Until the last days, this theme will be cross-cutting in the poet’s work. This collection is marked by a new quality of Mandelstam’s lyrical hero. For him, there is no longer any personal time that is not involved in the general flow of time. The voice of the lyrical hero can only be heard as an echo of the roar of the era. What happens in big history is perceived by him as the collapse and construction of a “temple” of his own personality.

The collection Tristia also reflected a significant change in the poet’s style. The figurative texture is moving more and more towards encrypted, “dark” meanings, semantic shifts, and irrational linguistic moves.

Wandering around Russia

Osip Mandelstam in the early 1920s. wandered mainly around the southern part of Russia. He visited Kyiv, where he met his future wife N. Ya. Khazina (pictured above), spent some time with Voloshin in Koktebel, then went to Feodosia, where Wrangel’s counterintelligence arrested him on suspicion of espionage. Then, after his release, he went to Batumi and was marked by a new arrest - this time by the Menshevik coast guard. Osip Emilievich was rescued from prison by T. Tabidze and N. Mitsishvili, Georgian poets. In the end, extremely exhausted, Osip Mandelstam returned to Petrograd. His biography continues with the fact that he lived for some time in the House of Arts, then again went south, after which he settled in Moscow.

However, by the mid-1920s, not a trace remained of the former balance of hopes and anxieties in understanding what was happening. The consequence of this is the changed poetics of Mandelstam. “Darkness” now increasingly outweighs clarity in it. In 1925, there was a short burst of creativity, which was associated with Olga Vaksel’s passion. After this, the poet falls silent for 5 long years.

For Mandelstam, the 2nd half of the 1920s was a period of crisis. At this time, the poet was silent and did not publish new poems. Not a single work by Mandelstam appeared in 5 years.

Appeal to prose

In 1929, Mandelstam decided to turn to prose. He wrote the book "The Fourth Prose". It is not large in volume, but it fully expresses Mandelstam’s contempt for the opportunist writers who were members of MASSOLIT. For a long time, this pain accumulated in the poet’s soul. “The Fourth Prose” expressed Mandelstam’s character - quarrelsome, explosive, impulsive. It was very easy for Osip Emilievich to make enemies for himself; he did not hide his judgments and assessments. Thanks to this, Mandelstam was always, almost all the post-revolutionary years, forced to exist in extreme conditions. He was awaiting imminent death in the 1930s. There weren’t very many admirers of Mandelstam’s talent and his friends, but they still existed.

Life

Attitude to everyday life largely reveals the image of a person like Osip Mandelstam. The biography, interesting facts about him, and the poet’s work are connected with his special attitude towards him. Osip Emilievich was not adapted to settled life, to everyday life. For him, the concept of a fortified house, which was very important, for example, for M. Bulgakov, had no meaning. The whole world was home for him, and at the same time Mandelstam was homeless in this world.

Remembering Osip Emilievich in the early 1920s, when he received a room in the Petrograd House of Arts (like many other writers and poets), K.I. Chukovsky noted that there was nothing in it that belonged to Mandelstam, except cigarettes. When the poet finally got an apartment (in 1933), B. Pasternak, who visited him, said as he left that he could now write poetry - there was an apartment. Osip Emilievich became furious at this. O. E. Mandelstam, whose biography is marked by many episodes of intransigence, cursed his apartment and even offered to return it to those to whom it was apparently intended: artists, honest traitors. It was the horror of realizing the price that was required for it.

Work at Moskovsky Komsomolets

Are you wondering how the life of a poet like Mandelstam continued? The biography by dates smoothly approached the 1930s in his life and work. N. Bukharin, Osip Emilievich’s patron in power circles, hired him at the turn of the 1920s and 30s to work as a proofreader for the Moskovsky Komsomolets newspaper. This gave the poet and his wife at least a minimal means of subsistence. But Mandelstam refused to accept the “rules of the game” of the Soviet writers who served the regime. His extreme impetuosity and emotionality greatly complicated Mandelstam’s relationships with his colleagues. He found himself at the center of a scandal - the poet was accused of translation plagiarism. In order to protect Osip Emilievich from the consequences of this scandal, in 1930 Bukharin organized a trip for the poet to Armenia, which made a great impression on him and was also reflected in his work. In the new poems, hopeless fear and the last courageous despair can be heard more clearly. If Mandelstam in prose tried to escape from the storm hanging over him, now he has finally accepted his share.

Awareness of the tragedy of one's fate

The awareness of the tragedy of his own fate and the choice he made probably strengthened Mandelstam and imparted a majestic, tragic pathos to his new works. It consists in confronting the personality of a free poet with the “beast age.” Mandelstam does not feel like a pathetic victim, an insignificant person in front of him. He feels equal to him. In the 1931 poem “For the explosive valor of the coming centuries,” which was called “The Wolf” in his home circle, Mandelstam predicted his future exile to Siberia, his own death, and poetic immortality. This poet understood many things earlier than others.

An ill-fated poem about Stalin

Yakovlevna, the widow of Osip Emilievich, left two books of memoirs about her husband, which tell about the sacrificial feat of this poet. Mandelstam's sincerity often bordered on suicide. For example, in November 1933, he wrote a sharply satirical poem about Stalin, which he read to many of his acquaintances, including B. Pasternak. Boris Leonidovich was alarmed by the fate of the poet and declared that his poem was not a literary fact, but nothing more than an “act of suicide,” which he could not approve of. Pasternak advised him not to read this work anymore. However, Mandelstam could not remain silent. The biography, the interesting facts from which we have just cited, from this moment becomes truly tragic.

The sentence for Mandelstam, surprisingly, was quite lenient. At that time, people also died for much less significant “offences.” Stalin's resolution simply said: "Isolate, but preserve." Mandelstam was sent into exile in the northern village of Cherdyn. Here Osip Emilievich, suffering from mental illness, even wanted to commit suicide. Friends helped again. N. Bukharin, already losing influence, wrote for the last time to Comrade Stalin that poets are always right, that history is on their side. After this, Osip Emilievich was transferred to Voronezh, to less harsh conditions.

Of course, his fate was sealed. However, in 1933, punishing him severely meant advertising a poem about Stalin and thus, as if settling personal scores with the poet. And this would, of course, be unworthy of Stalin, the “father of nations.” Joseph Vissarionovich knew how to wait. He understood that everything has its time. In this case, he expected the great terror of 1937, in which Mandelstam was destined, along with hundreds of thousands of other people, to perish unknown.

Years of life in Voronezh

Voronezh sheltered Osip Emilievich, but sheltered him with hostility. However, Osip Emilievich Mandelstam did not stop fighting the despair that was steadily approaching him. His biography during these years was marked by many difficulties. He had no means of livelihood, people avoided meeting him, and his future fate was unclear. Mandelstam felt with his whole being how the “age-beast” was overtaking him. And Akhmatova, who visited him in exile, testified that in his room “fear and the muse were alternately on duty.” The poems flowed unstoppably, they demanded an outlet. Memoirists testify that Mandelstam once rushed to a pay phone and began reading his new works to the investigator to whom he was assigned at the time. He said that there was no one else to read. The poet's nerves were exposed; he poured out his pain in poetry.

In Voronezh, from 1935 to 1937, three “Voronezh notebooks” were created. For a long time, the works of this cycle were not published. They could not be called political, but even “neutral” poems were perceived as a challenge, since they represented Poetry, unstoppable and uncontrollable. And for the authorities it is no less dangerous, since, in the words of I. Brodsky, it “shakes the entire way of life,” and not just the political system.

Return to the capital

Many poems of this period, as well as Mandelstam’s works of the 1930s in general, are imbued with a feeling of imminent death. The Voronezh exile expired in May 1937. Osip Emilievich spent another year in the vicinity of Moscow. He wanted to get permission to stay in the capital. However, magazine editors categorically refused not only to publish his poems, but also to talk to him. The poet was a beggar. Friends and acquaintances helped him at this time: B. Pasternak, V. Shklovsky, V. Kataev, although they themselves had a hard time. Anna Akhmatova later wrote about 1938 that it was an “apocalyptic” time.

Arrest, exile and death

It remains for us to tell very little about such a poet as Osip Mandelstam. His brief biography is marked by a new arrest, which took place on May 2, 1938. He was sentenced to five years' hard labor. The poet was sent to the Far East. He never returned from there. On December 27, 1938, near Vladivostok, in the Second River camp, the poet died.

We hope you would like to continue your acquaintance with such a great poet as Mandelstam. Biography, photo, creative path - all this gives some idea about him. However, only by turning to Mandelstam’s works can one understand this man and feel the strength of his personality.

Mandelstam Osip Emilievich (1891─1938) - an outstanding Russian and Soviet poet, translator, prose writer, essayist. Thanks to his lofty lyricism and attempts to rethink world history and culture in a single context, he became one of the largest figures in Russian poetry of the 20th century. His poems are imbued with deep associative symbols coming from ancient traditions. Often in the poet's work one can see architectural images that emphasize the harmony and clarity of his verbal forms. Mandelstam’s collections of poems “Stone” and “Trisyia”, as well as the collection of prose “The Noise of Time” are well known to a wide range of readers.

Childhood and youth

Osip Mandelstam was born on January 3 (15), 1891 in Warsaw. His father Emil Veniaminovich was engaged in the leather business, then turned into a successful businessman, becoming a merchant of the first guild. Mother Flora Osipovna was a relative of the historian of Russian literature S. Vengerov and taught music. A year after the birth of the boy, the family moved to Pavlovsk, and in 1897 they moved to St. Petersburg.

Living in the capital of the Russian Empire and having a strong desire from his parents to give their sons a good start in life, Mandelstam received an excellent humanities education. Since 1899, he studied at the prestigious Tenishevsky Commercial School, the director of which and at the same time a teacher of literature was the symbolist poet V. Gippius. It was during his years there that he became interested in theater, music and, of course, poetry.

Thanks to the teacher, a turning point occurs in the consciousness of the future poet. At first fascinated by the revolutionary stylistics of S. Nadson, Mandelstam discovered the work of the Symbolists. The greatest influence on him was the poems of F. Sologub and V. Bryusov. Therefore, the first adult attempts to write have something in common with their works.

After graduating from college in 1907, Mandelstam left for Paris to attend a course of lectures at the literature department at the Sorbonne. This trip was largely facilitated by the family, who were frightened by the revolutionary sentiments of their son. There he was able to penetrate the depth of the Old French epic and became interested in the work of the famous French poets C. Baudelaire, P. Verlaine, F. Villon. In 1910-1911, the poet studied for two semesters at the University of Heidelberg in Berlin, learning the wisdom of philosophy. He also lived for some time in Switzerland. In 1911 he was baptized at the Vyborg Methodist Church.

Due to the worsening financial situation of the family, the poet interrupts his studies. After returning to Russia, he entered the Faculty of History and Philology of St. Petersburg University, where he studied in the department of Romance languages. In 1911, Osip Emilievich met Anna Akhmatova and N. Gumilev, with whom he developed a close friendship. For the first time, he became close to people about whom he confidently spoke the word “we.” Later, he admitted to the great poetess that he could have an imaginary conversation with only two people - with her and her husband N. Gumilyov.

In the poetic field

While studying in Europe, Mandelstam came to St. Petersburg from time to time, where he developed connections with the local literary community. He enjoyed listening to a course of lectures in the most famous citadel of symbolism - the famous “tower” of the symbolist theorist V. Ivanov. In his apartment on the top floor the whole flower of Russian art of the “Silver Age” gathered - A. Blok, A. Akhmatova, N. Berdyaev, M. Voloshin and others. Many great works were performed here for the first time, for example, “The Stranger” by A. Blok.

Mandelstam's first five poems were published in 1910 in the Russian illustrated magazine Apollo. These poems were largely anti-symbolic, in them the “deep world” was opposed to prophetic pathos. Three years later, the poet’s first collection of poems, entitled “Stone,” was published by the Akme publishing house. It contains works written in the period 1908 - 1911.

A certain spirit of symbolism can be traced in them, but without the otherworldliness inherent in its authentic form. Now symbolic skills had to reflect three-dimensional realities, refracted through a certain architectural content, in which he sees a clear content and structure. Hence the completely unpoetic title of the collection. With the appearance of “The Stone,” Mandelstam immediately took his place among the largest Russian poets. In 1915, the Hyperborea publishing house republished the book, supplementing it with poems from the last two years.

Mandelstam joined the group of Acmeists created in 1912, who opposed themselves to the Symbolists and defended the materiality of images expressed using precise words. In addition, he was a member of the St. Petersburg association “Workshop of Poets”, founded by O. Gorodetsky and N. Gumilev. One of the main goals proclaimed here was an attempt to distance itself from symbolism. True, for Mandelstam, his stay in these communities was dictated more by motives of friendship than by adherence to the ideas of Acmeism. Therefore, during this period, the poet’s most optimistic poems were written, for example, “Casino,” which contains the following lines:

I'm not a fan of biased joy

Sometimes nature is a gray spot

I, in a slight intoxication, am destined

Experience the colors of a poor life

From the very first years of his creativity, Mandelstam felt himself a part of the world cultural space and saw this as a manifestation of his own freedom. In this imaginary world there was a place for Pushkin and Dante, Ovid and Goethe. In 1916, the poet met M. Tsvetaeva, which developed into friendship. They even dedicated several works to each other.

"Tristia" period

Poems written in the midst of revolutionary events and the Civil War formed the basis of a new collection, which was called “Tristia”. In it, the core of Mandelstam’s poetic world became the ancient style, which turned into the author’s speech, reflecting his innermost experiences. Actually, the word “triastia” is found in Ovid and means parting. As in “Stone,” the poems here are also cyclical, but even more closely related to each other. Mandelstam loved to repeat words in poems, filling them with special meaning. During this period, a more complex attitude of the author to words and images, which become more irrational, can be traced. Interestingly, the collections themselves also have a connection: “Stone” ends, and “Tristia” begins with lines about Phaedrus.

Such an expressive retreat into the ancient model of existence, which serves as a kind of cultural code, was the result of serious political changes and, above all, the coming to power of the Bolsheviks. Like many representatives of the Russian intelligentsia, Mandelstam initially did not accept the new government and even wrote a poem in support of the ousted head of the Provisional Government A. Kerensky. It contains the following multi-valued lines:

When the October one was prepared for us by a temporary worker

Yoke of violence and malice

He personified the new revolutionary idea with the destruction of order and the establishment of chaos. And this led the poet to real horror. But the ideological pendulum of contradictions from which Mandelstam’s worldview and creativity were woven swung to the side and he soon accepted Soviet power, which was reflected in the writing of the poem “Twilight of Freedom.”

Mandelstam in the 1920s

The period of the relatively liberal NEP coincided with Mandelstam's active literary work. In 1923, a new collection, “The Second Book,” was published, and his poems began to be published abroad. The poet writes a series of articles devoted to key problems of culture, history and humanism - “On the nature of the word”, “Human wheat” and others. In 1925, the autobiographical collection “The Noise of Time” was published, which became a kind of oratorio of the era with deeply personal memories. Along with this, several children's collections were released.

At this time, Osip Emilievich was actively engaged in translation activities, adapting the works of Petrarch, O. Barbier, F. Werfel and many other foreign authors into Russian. During the persecution, it was this work that became a creative outlet where one could express oneself. It is no coincidence that many critics note that poems translated by the poet sometimes sound better than the author’s.

In 1930, Mandelstam visited Armenia and was impressed by what he saw. This coveted (as the poet himself said) country had long attracted him with its history and culture. As a result, “Journey to Armenia” and the cycle of poems “Armenia” were written.

Conflict with the authorities

In 1933, Osip Emilievich wrote a poetic invective directed against I. Stalin. It began with the following lines:

We live without feeling the country beneath us

Our speeches are inaudible ten steps away

Despite the bewilderment of those around him (according to B. Pasternak, it was suicide) caused by the reckless courage of the author, he said: “Poems should now be civil”. The poet read this work to many friends, relatives and acquaintances, so now it is difficult to determine who reported it. But the reaction of the Soviet authorities was lightning fast. By order of the then head of the NKVD G. Yagoda, Mandelstam was arrested in his own apartment in May 1934. During this procedure, a total search was carried out - it is difficult to name the places where the inspectors did not look.

True, the most valuable manuscripts were kept by relatives. There is another version of possible disgrace. Shortly before these events, during a tense conversation, the poet hit A. Tolstoy on the cheek and he promised that he would not just leave it like that.

B. Pasternak and A. Akhmatova interceded for the great poet, and prominent party leader N. Bukharin, who highly valued his work, also tried to help Osip. Perhaps, thanks to his patronage, Mandelstam was sent first to the Northern Urals to the city of Cherdyn, and from there he was transferred to a three-year exile in Voronezh. Here he worked in a newspaper and on the radio, leaving his spiritual confession in the form of three notebooks of poetry.

After his release, he will be prohibited from living in the capital, and the poet will go to Kalinin. But he did not stop writing poetry and was soon arrested again, receiving 5 years in the camps for allegedly counter-revolutionary activities. The sick and weakened Osip Emilievich could no longer stand the new turn of fate. He died on December 27, 1938 in Vladivostok in a hospital barracks.

Personal life

Osip Mandelstam was married to Nadezhda Khazina, whom he met in 1919 in the Kiev cafe “H.L.A.M.” After the wedding, which took place in 1922, she will become the faithful companion of the freedom-loving poet and will go through with him all the difficulties of the disgraced period. In addition, Mandelstam was not at all adapted to everyday life, and she had to look after him like a child. Nadezhda Yakovlevna left brilliant memoirs, despite the contradictory assessments, which became an important source for studying Mandelstam’s creative heritage.

Osip 1 Emilievich Mandelstam was born on January 3, 1891 in Warsaw; he spent his childhood and youth in St. Petersburg. Later, in 1937, Mandelstam wrote about the time of his birth:

I was born on the night from the second to the third of January in the ninety-one Unreliable Year... ("Poems about the Unknown Soldier")Here “into the night” contains an ominous omen of the tragic fate of the poet in the twentieth century and serves as a metaphor for the entire twentieth century, according to Mandelstam’s definition - “the century of the beast.”

Mandelstam's memories of his childhood and youth are restrained and strict; he avoided revealing himself, commenting on himself and his poems. He was an early ripened, or rather, a poet who saw the light, and his poetic manner is distinguished by seriousness and severity.

What little we find in the poet’s memoirs about his childhood, about the atmosphere that surrounded him, about the air that he had to breathe, is rather painted in gloomy tones:

From the pool of evil and viscous I grew up, rustling like a reed, and passionately, languidly, and affectionately breathing the forbidden life. ("From the whirlpool of evil and viscous...")"Forbidden Life" is about poetry.

Mandelstam’s family was, in his words, “difficult and confused,” and this was manifested with particular force (at least in the perception of Osip Emilievich himself) in words, in speech. The speech “element” of the family was unique. Father, Emilius Veniaminovich Mandelstam, a self-taught businessman, was completely devoid of a sense of language. In the book “The Noise of Time,” Mandelstam wrote: “My father had no language at all, it was tongue-tied and tongueless... A completely abstract, invented language, the florid and twisted speech of a self-taught person, the bizarre syntax of a Talmudist, an artificial, not always agreed upon phrase.” The speech of the mother, Flora Osipovna, a music teacher, was different: “Clear and sonorous, literary great Russian speech; its vocabulary is poor and condensed, its turns are monotonous - but this is a language, there is something radical and confident in it.” From his mother, Mandelstam inherited, along with a predisposition to heart disease and musicality, a heightened sense of the Russian language and accuracy of speech.

In 1900-1907, Mandelstam studied at the Tenishevsky Commercial School, one of the best private educational institutions in Russia (V. Nabokov and V. Zhirmunsky studied there at one time).

After graduating from college, Mandelstam traveled abroad three times: from October 1907 to the summer of 1908 he lived in Paris, from the autumn of 1909 to the spring of 1910 he studied Romance philology at the University of Heidelberg in Germany, from July 21 to mid-October he lived in the Berlin suburb of Zehlendorf. The echo of these meetings with Western Europe can be heard in Mandelstam's poems right up to his last works.

The formation of Mandelstam's poetic personality was determined by his meeting with N. Gumilev and A. Akhmatova. In 1911, Gumilyov returned to St. Petersburg from the Abyssinian expedition, and all three then often met at various literary evenings. Subsequently, many years after the execution of Gumilyov, Mandelstam wrote to Akhmatova that Nikolai Stepanovich was the only one who understood his poems and with whom he talks and conducts dialogues to this day. Mandelstam’s attitude towards Akhmatova is most clearly evidenced by his words: “I am a contemporary of Akhmatova.” To publicly declare this during the years of the Stalinist regime, when the poetess was disgraced, one had to be Mandelstam.

All three, Gumilyov, Akhmatova, Mandelstam, became the creators and most prominent poets of a new literary movement - Acmeism. Biographers write that at first there was friction between them, because Gumilyov was despotic, Mandelstam was quick-tempered, and Akhmatova was capricious.

Mandelstam's first collection of poetry was published in 1913; it was published at his own expense 2 . It was assumed that it would be called "Sink", but the final name was chosen differently - "Stone". The name is quite in the spirit of Acmeism. The Acmeists sought to rediscover the world, as it were, to give everything a clear and courageous name, devoid of the elegiac hazy flair of the Symbolists. Stone is a natural material, durable and solid, an eternal material in the hands of a master. For Mandelstam, stone is the primary building material of spiritual, and not just material, culture.

In 1911-1917, Mandelstam studied at the Romance-Germanic department of the Faculty of History and Philology of St. Petersburg University.

Mandelstam's attitude towards the 1917 revolution was complex. However, any attempts by Mandelstam to find his place in the new Russia ended in failure and scandal. The second half of the 1920s for Mandelstam were years of crisis. The poet was silent. There were no new poems. In five years - not a single one.

In 1929, the poet turned to prose and wrote a book called “The Fourth Prose.” It is small in volume, but it fully expresses the pain and contempt of the poet for opportunistic writers (“members of MASSOLIT”) that had been accumulating for many years in Mandelstam’s soul. "The Fourth Prose" gives an idea of the poet's character - impulsive, explosive, quarrelsome. Mandelstam very easily made enemies for himself; he did not hide his assessments and judgments. From “The Fourth Prose”: “I divide all works of world literature into those that were authorized and those written without permission. The former are scum, the latter are stolen air. I want to spit in the face of writers who write pre-authorized things, I want to hit them on the head with a stick and seat everyone at the table in the Herzen House, placing a glass of police tea in front of each and giving each one a Gornfeld urine test.

I would forbid these writers to marry and have children - after all, the children must continue for us, the most important thing to finish for us - while the fathers are sold to the pockmarked devil for three generations ahead."

One can imagine the intensity of mutual hatred: the hatred of those whom Mandelstam rejected and who rejected Mandelstam. The poet always, almost all the post-revolutionary years, lived in extreme conditions, and in the 1930s - in anticipation of inevitable death. There weren’t many friends and admirers of his talent, but they were there.

Mandelstam early realized himself as a poet, as a creative person who was destined to leave his mark on the history of literature and culture, and moreover, “to change something in its structure and composition” (from a letter to Yu.N. Tynyanov). Mandelstam knew his worth as a poet, and this was manifested, for example, in an insignificant episode that V. Kataev describes in his book “My Diamond Crown”:

“Having met the nutcracker (i.e. Mandelstam) on the street, one writer acquaintance very friendly asked the nutcracker a traditional secular question:

What new things have you written?

To which the nutcracker suddenly, completely unexpectedly, broke free of the chain:

If I had written something new, the whole of Russia would have known about it long ago! And you are ignorant and vulgar! - the nutcracker shouted, shaking with indignation, and pointedly turned his back on the tactless fiction writer." 3

Mandelstam was not adapted to everyday life, to a settled life. The concept of home, home-fortress, very important, for example, in the artistic world of M. Bulgakov, was not significant for Mandelstam. For him, home is the whole world, and at the same time in this world he is homeless.

K.I. Chukovsky recalled Mandelstam in the early 1920s, when he, like many other poets and writers, received a room in the Petrograd House of Arts: “In the room there was nothing belonging to him, except cigarettes, not a single personal thing. And then I I understood its most striking feature - its non-existence." In 1933, Mandelstam finally received a two-room apartment! B. Pasternak, who visited him, left and said: “Well, now we have an apartment - we can write poetry.” Mandelstam was furious. He cursed the apartment and offered to return it to those for whom it was intended: honest traitors, imagers. It was terrifying in front of the payment that was required for the apartment.

The consciousness of the choice made, the awareness of the tragedy of his fate, apparently strengthened the poet, gave him strength, and imparted a tragic, majestic pathos to his new poems 4. This pathos lies in the opposition of a free poetic personality to his age - the “beast age”. The poet does not feel insignificant in front of him, a pathetic victim, he realizes himself as an equal:

...The age-wolfhound throws itself on my shoulders, But I am not a wolf by blood, Stuff me better, like a hat, into the sleeve of the Hot fur coat of the Siberian steppes, Take me into the night, where the Yenisei flows, And the pine tree reaches the star, Because I am not a wolf by blood and only an equal will kill me. March 17-28, 1931 (“For the explosive valor of the coming centuries...”)In the home circle this poem was called "Wolf". In it, Osip Emilievich predicted his future exile to Siberia, his physical death, and his poetic immortality. He understood a lot earlier than others.

Nadezhda Yakovlevna Mandelstam, whom E. Yevtushenko called “the greatest widow of the poet in the twentieth century,” left two books of memories about Mandelstam - about his sacrificial feat as a poet. From these memoirs one can understand, “even without knowing a single line of Mandelstam, that on these pages they remember a truly great poet: in view of the amount and power of evil directed against him.”

Mandelstam's sincerity bordered on suicide. In November 1933 he wrote a sharply satirical poem about Stalin:

We live without feeling the country beneath us, Our speeches cannot be heard ten steps away, And where there is enough for half a conversation, There they will remember the Kremlin highlander. His thick fingers are fat like worms, And his words are true like weights. The cockroach's whiskers laugh, And his boots shine. And around him is a rabble of thin-necked leaders, He plays with the services of semi-humans. Who whistles, who meows, who whines, He alone babbles and pokes. Like a decree, a decree forges horseshoes - Some in the groin, some in the forehead, some in the eyebrow, some in the eye. No matter what he has, he has raspberries and a broad Ossetian chest.And Osip Emilievich read this poem to many acquaintances, including B. Pasternak. Anxiety for the fate of Mandelstam prompted Pasternak to declare in response: “What you read to me has nothing to do with literature, poetry. This is not a literary fact, but an act of suicide, which I do not approve of and in which I do not want to take part. I didn’t read anything, I didn’t hear anything, and I ask you not to read them to anyone.” Yes, Pasternak is right, the value of this poem does not lie in its literary merits. The first two lines here are at the level of the best poetic discoveries:

We live without feeling the country beneath us, Our speeches cannot be heard ten steps away...Surprisingly, the sentence given to Mandelstam was rather lenient. People at that time died for much lesser “offenses.” Stalin’s resolution simply read: “Isolate, but preserve,” and Osip Mandelstam was sent into exile in the distant northern village of Cherdyn. In Cherdyn, Mandelstam, suffering from mental illness, tried to commit suicide. Friends helped again. N. Bukharin, already losing his influence, wrote to Stalin for the last time: “Poets are always right; history is on their side”; Mandelstam was transferred to less harsh conditions - to Voronezh.

Of course, Mandelstam's fate was predetermined. But to punish him severely in 1933 would have meant publicizing that ill-fated poem and, as it were, settling personal scores between the tyrant and the poet, which would have been clearly unworthy of the “father of nations.” Everything has its time, Stalin knew how to wait, in this case - the great terror of 1937, when Mandelstam was destined to perish unknown along with hundreds of thousands of others.

Voronezh sheltered the poet, but sheltered him with hostility. From Voronezh notebooks (unpublished during his lifetime):

Let me go, give me back, Voronezh, - Will you drop me or miss me, Will you drop me or bring me back - Voronezh is a whim, Voronezh is a raven, a knife! 1935 Voronezh What street is this? 5 Mandelstam Street. What a damn name! - No matter how you twist it, it sounds crooked, not straight. There was little linear about him. He was not of a lily disposition, and therefore this street, or rather, this pit, is called by the name of this Mandelstam. April, 1935 VoronezhThe poet struggled with approaching despair: there was no means of subsistence, people avoided meeting him, his future fate was unclear, and with all his being as a poet, Mandelstam felt: the “beast of the century” was overtaking him. A. Akhmatova, who visited Mandelstam in exile, testifies:

And in the room of the disgraced poet, fear and the muse are on duty in their turn. And the night goes by, which knows no dawn. ("Voronezh")“Fear and the muse are on duty...” The poems came unstoppably, “irretrievably” (as M. Tsvetaeva said at the same time - in 1934), they demanded an outlet, they demanded to be heard. Memoirists testify that one day Mandelstam rushed to a pay phone and read new poems to the investigator to whom he was assigned: “No, listen, I have no one else to read to!” The poet's nerves were exposed, and he poured out his pain in poetry.

The poet was in a cage, but he was not broken, he was not deprived of the inner secret of freedom that raised him above everyone even in captivity:

Having deprived me of the seas, run-up and flight, and given my foot the support of the violent earth, what have you achieved? Brilliant calculation: You couldn’t take away the moving lips.The poems of the Voronezh cycle remained unpublished for a long time. They were not, as they say, political, but even “neutral” poems were perceived as a challenge, because they represented Poetry, uncontrollable and unstoppable. And no less dangerous for the authorities, because “a song is a form of linguistic disobedience, and its sound casts doubt on much more than a specific political system: it shakes the entire way of life” (I. Brodsky).

Mandelstam's poems stood out sharply against the background of the general flow of official literature of the 1920s and 30s. Time demanded the poems it needed, like the famous poem by E. Bagritsky “TVS” (1929):

And the century waits on the pavement, Concentrated like a sentry. Go - and don’t be afraid to stand next to him. Your loneliness matches the age. You look around and there are enemies all around; You stretch out your hands and there are no friends. But if he says, “Lie,” lie. But if he says: “Kill,” kill.Mandelstam understood: he could not stand “next to the century”; his choice was different - opposition to the cruel time.

Poems from the Voronezh notebooks, like many of Mandelstam’s poems of the 1930s, are imbued with a feeling of imminent death; sometimes they sound like spells, alas, unsuccessful:

I have not yet died, I am not yet alone, While with my beggar friend I enjoy the grandeur of the plains And the darkness, and hunger, and the blizzard. In beautiful poverty, in luxurious poverty I live alone - calm and comforted - Blessed are those days and nights, And the mellifluous labor is sinless. Unhappy is the one who, like his shadow, is frightened by barking and mowed down by the wind, And poor is the one who, half-dead himself, begs for alms from the shadow. January 1937 VoronezhIn May 1937, the Voronezh exile expired. The poet spent another year in the vicinity of Moscow, trying to obtain permission to live in the capital. Magazine editors were even afraid to talk to him. He was a beggar. Friends and acquaintances helped: V. Shklovsky, B. Pasternak, I. Erenburg, V. Kataev, although it was not easy for them themselves. Subsequently, A. Akhmatova wrote about 1938: “It was an apocalyptic time. Trouble followed on the heels of all of us. The Mandelstams had no money. They had absolutely nowhere to live. Osip was breathing poorly, catching air with his lips.”

On May 2, 1938, before sunrise, as was customary then, Mandelstam was arrested again, sentenced to 5 years of hard labor and sent to Western Siberia, the Far East, from where he would never return. A letter from the poet to his wife has been preserved, in which he wrote: “My health is very poor, I’m extremely exhausted, I’m emaciated, I’m almost unrecognizable, but I don’t know if it makes sense to send things, food and money. Try it anyway. I’m very cold without things.” .

The poet’s death occurred in the Vtoraya Rechka transit camp near Vladivostok on December 27, 1938... One of the poet’s last poems:

The mounds of people's heads recede into the distance, I shrink there - no one will notice me, But in gentle books and in children's games I will rise again to say that the sun is shining. 1936-1937?M.Gorka

Introduction

The work of O.E. Mandelstam is a rare example of the unity of poetry and fate. Life in poetry is what biography was subordinated to, acquiring true significance only in the light of aesthetic eternity. Moreover, the fate of Mandelstam itself becomes a symbol of the time and acquires a general meaning. Constantly under suspicion as a “renegade in the people’s family,” living in fear of arrest and ultimately crushed by the ruthless machine of suppression of freedom, O. Mandelstam truly earned the right to “speak for everyone.” His work is interesting as evidence of an eyewitness to the events, who shared the pain of his country to the end and defended the right to freedom of creativity in the face of inevitable death.

O. Mandelstam is a poet who reflected in his heritage the true quest of the 20th century. In his lyrics, the modernist tendency is combined with the classicism of style, themes, and motifs. A most complex poet, a deep thinker, an atypical prose writer, Mandelstam will never cease to be relevant.

Despite the abundance of works on Mandelstam’s work that have appeared over the past decade and a half, he still remains a rather mysterious figure. Understanding his work requires a certain key, and many poems are still not “deciphered.” Particularly relevant for study is the concept of Mandelstam’s creativity, multifaceted and truly unique. Her research can shed light on many difficult-to-interpret semantic passages in Mandelstam’s works.

The concept of Mandelstam's creativity in its depth and unusualness is one of the most striking in Russian literature of the 20th century. It is of particular interest for research due to the fact that it occupies a central place in Mandelstam’s worldview and artistic system.

The creative legacy of O. Mandelstam, in all its depth and multifaceted nature, does not seem to be fully and comprehensively studied. At the moment, Mandela studies tends to raise more questions than it answers. There are still many ambiguities due to the lack of sources: they concern the facts of the poet’s biography (especially his stay in the camp), establishing the final version of many poems. Currently, O. Mandelstam's archive is stored at Princeton University in the USA, which creates additional difficulties for studying his work.

Life and work of O.E. Mandelstam

Osip Emilievich Mandelstam is a poet, prose writer, critic, translator, whose creative contribution to the development of Russian literature requires careful historical and literary analysis.

Osip Emilievich Mandelstam was born on January 3 (15), 1891 in Warsaw into the family of a businessman who was never able to create a fortune. But Petersburg became the Poet’s hometown: here he grew up and graduated from one of the best schools in Russia at that time, the Tenishev School. Here he survived the 1905 revolution. It was perceived as the “glory of the century” and a matter of valor. Mandelstam, being a Jew, chooses to be a Russian poet - not just “Russian-speaking,” but precisely Russian. And this decision is not so self-evident: the beginning of the century in Russia was a time of rapid development of Jewish literature, both in Hebrew and Yiddish, and, partly, in Russian. Mandelstam made the choice in favor of Russian poetry and “Christian culture.”

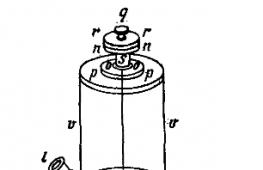

O. E. Mandelstam.

Voronezh. 1935

He was pushed towards poetry by the lessons of the symbolist V.V. Gipplus, who read Russian literature at the school. Then Mandelstam studied at the Romano-Germanic department of the university's philological faculty. Soon after this he left the city on the Neva. Mandelstam will return here again, “to a city familiar to tears, to veins, to children’s swollen glands.” Meetings with the “northern capital”, “Transparent Petropolis”, where “the narrow canals under the ice are even blacker”, will be frequent in poems generated by both the feeling of involvement of one’s fate in the fate of one’s native city, and admiration for its beauty.

Mandelstam’s entire work can be divided into six periods:

1908 - 1911 are “years of study” abroad and then in St. Petersburg, poems in the tradition of symbolism;

1912 – 1915 – St. Petersburg, Acmeism, “material” poems, work on “Stone”;

1916 – 1920 – revolution and civil war, wanderings, outgrowing Acmeism, developing an individual manner;

1921 – 1925 – intermediate period, gradual departure from poetry;

1926 – 1929 – dead poetic pause, translations;

1930 – 1934 – trip to Armenia, return to poetry, “Moscow poems”;

1935 – 1937 – the last, “Voronezh” poems.

The first, earliest, stage of Mandelstam’s creative evolution is associated with his “study” with the Symbolists, with participation in the Acmeist movement. At this stage, Mandelstam appears in the ranks of Acmeist writers. But how obvious is his specialness in their midst! The poet, who did not seek paths to revolutionary circles, came to an environment that was largely alien to him. He was probably the only Acmeist who so clearly felt the lack of contacts with the “sovereign world.” Subsequently, in 1931, in the poem “I was only childishly connected with the world of power...” Mandelstam said that in his youth he forcibly forced himself to “assimilate” into an alien literary circle, merged with the world, which did not give Mandelstam real spiritual values :

And I don’t owe him a single grain of my soul,

No matter how much I tortured myself in someone else’s image.

The early poem “The cloudy air is humid and booming...” directly speaks of the alienation and dissociation that oppresses many people in the “indifferent fatherland” - Tsarist Russia:

I'm taking part in a dark life

Where one to one is lonely!

This awareness of social loneliness gave rise to deeply individualistic sentiments in Mandelstam, leading him to search for “quiet freedom” in individualistic existence, to the illusory concept of self-delimitation of man from society:

Dissatisfied, I stand and remain quiet

I am the creator of my worlds...

(“The thin decay is thinning out...”)

Mandelstam, a sincere lyricist and skilled craftsman, finds here extremely precise words that define his state: yes, he is dissatisfied, but also quiet, humble and humble, his imagination paints for him some illusory, fantasized world of peace and reconciliation. But the real world stirs his soul, hurts his heart, disturbs his mind and feelings. And hence, in his poems, the motives of dissatisfaction with reality and with oneself “spread” so widely throughout their lines.

In this “denial of life,” in this “self-abasement” and “self-flagellation,” the early Mandelstam has something in common with the early symbolists. Young Osip Mandelstam is also brought together by the early symbolists by the feeling of the catastrophic nature of the modern world, expressed in the images of the abyss, the abyss, the emptiness surrounding it. However, unlike the symbolists, Mandelstam does not attach any ambiguous, ambiguous, mystical meanings to these images. He expresses a thought, a feeling, a mood in “unambiguous” images and comparisons, in precise words that sometimes acquire the character of definitions. His poetic world is material, objective, sometimes “puppet-like.” In this one cannot help but feel the influence of those demands that, in search of “overcoming symbolism,” were put forward by pre-Acmeist and Acmeist theorists and poets - the demands of “beautiful clarity” (M. Kuzmin), the objectivity of details, the materiality of images (S. Gorodetsky).

In lines like:

A little red wine

A little sunny May -

And, breaking a thin biscuit,

The thinnest fingers are white, -

("Unspeakable sadness...")

Mandelstam is unusually close to M. Kuzmin, to the colorfulness and concreteness of details in his poems. In 1910, the “crisis of symbolism”—the exhaustion of the political system—became indisputable. In 1911, young poets from students of symbolism, wanting to look for new paths, formed the “Workshop of Poets” - an organization chaired by N. Gumilyov and S. Gorodetsky. In 1912, within the Workshop of Poets, a core of six people was formed who called themselves Acmeists. These were N. Gumilyov, S. Gorodetsky, A. Akhmatova, O. Mandelstam, M. Zenkevich and V. Narbut. It would be difficult to imagine more dissimilar poets. The group existed for two years and disbanded with the outbreak of World War II; but Akhmatova and Mandelstam continued to feel like “Acmeists” until the end of their days, and among literary historians the word “Acmeism” increasingly began to mean the combination of both creative features of these two poets.

Acmeism for Mandelstam is “the complicity of beings in a conspiracy against emptiness and non-existence. Love the existence of a thing more than the thing itself and your being more than yourself - this is the highest commandment of Acmeism.” And the second is the creation of eternal art.

It was very important for Osip Emilievich to feel like he was in a circle of like-minded people, even if it was a very narrow one. He appeared in the Workshop of Poets at discussions and exhibitions, in the bohemian basement "Stray Dog". His raised crest, solemnity, childishness, enthusiasm, poverty and constant living on borrowed money - this is how his contemporaries remembered him. In 1913 he published a book of poems, and in 1916 it was republished, doubled in size. Of the early poems, only a small part was included in the book - not about “eternity, but about the sweet and insignificant.” The book was published under the title "Stone". Architectural poetry is the core of Mandelstam's "Stone". It is there that the acmeic ideal is expressed as a formula:

But the closer you look, the stronghold of Notre-Dame,

I studied your monstrous ribs

The more often I thought: out of unkind heaviness

And someday I will create something beautiful.

The last poems of "Stone" were written at the beginning of the World War. Like everyone else, Mandelstam greeted the war with enthusiasm; like everyone else, he was disappointed a year later.

He accepted the revolution unconditionally, connecting with it the idea of the beginning of a new era - the era of the establishment of social justice, a genuine renewal of life.

Well, let's try: huge, clumsy

Creaky steering wheel.

The earth is floating. Take courage, men,

Dividing the ocean like a plow.

We will remember in the cold of life,

That the earth cost us ten heavens.

In the winter of 1919, the opportunity opens up to travel to the less hungry south; he leaves for a year and a half. He later dedicated the essays “Theodosius” to his first trip. Essentially, it was then that the question was decided for him: to emigrate or not to emigrate. He did not emigrate. And about those who chose emigration, he wrote in the ambiguous poem “Where the night casts anchors...”: “Where are you flying? Why have you fallen away from the tree of life? Bethlehem is alien and terrible to you, And you have not seen the manger...”

In the spring of 1922, Mandelstam returned from the south and settled in Moscow. With him is his young wife, Nadezhda Yakovlevna. Osip Emilievich and Nadezhda Yakovlevna were completely inseparable. She was equal to her husband in intelligence, education, and enormous spiritual strength. She, of course, was a moral support for Osip Emilievich. His difficult tragic fate became her fate. She took this cross upon herself and carried it in such a way that it seemed that it could not have been otherwise. “Osip loved Nadya incredibly and unbelievably,” said Anna Akhmatova.

In the fall of 1922, a small book of new poems by Tristia was published in Berlin. (Mandelshtam wanted to call it “The New Stone.”) In 1923, it was republished in a modified form in Moscow under the title “The Second Book” (and with a dedication to Nadya Khazina). The poems of "Tristius" are sharply different from the poems of "Stone". This is the new second poetics of Mandelstam.

In the poem “On the Sledges...” the theme of death replaced the theme of love. In the poems about the favorite voice on the phone (“Your wonderful pronunciation…”) there are unexpected lines: “let them say: love is winged, death is a hundred times more winged.” The theme of death also came to Mandelstam from his own spiritual experience: his mother died in 1916. The only enlightening conclusion is the poem “Sisters - heaviness and tenderness...”: life and death are a cycle, a rose is born from the earth and goes into the earth, and it leaves the memory of its single existence in art.

But Mandelstam writes much more often and more alarmingly not about the death of a person, but about the death of the state. This poetics was a response to the catastrophic events of war and revolution. Three works sum up this revolutionary period of Mandelstam’s work - three and one more. The prologue is a small poem "Century":

My age, my beast, who can

Look into your pupils

And with his blood he will glue

Two centuries of vertebrae?

The century's spine was broken, the connection between times was interrupted, and this threatens the death of not only the old century, but also the newborn.

Of Mandelstam's contemporaries, perhaps only Andrei Platonov could even then so keenly feel the tragedy of the era, when the foundation pit that was being prepared for the construction of the majestic building of socialism became a grave for many working there. Among poets, Mandelstam was perhaps the only one who so early was able to consider the danger threatening a person who is completely subjugated by time. “A wolfhound century is throwing itself on my shoulders, But why am I not a wolf by blood…” What happens to a person in this era? Osip Emilievich did not want to separate his fate from the fate of the people, the country, and finally, from the fate of his contemporaries. He repeated this persistently and loudly:

It's time for you to know: I am also a contemporary,

I am a man of the Moscow seamstress era,

Look how my jacket is puffing up on me,

How can I walk and talk!

Try to tear me away from the eyelid! –

I guarantee you, you will break your neck!

In life, Mandelstam was neither a fighter nor a fighter. He knew ordinary human feelings, and among them was the feeling of fear. But, as the smart and poisonous V. Khodasevich noted, the poet combined “hare cowardice with almost heroic courage.” As for poetry, they reveal only that property of the poet’s nature that is named last. The poet was not a courageous man in the conventional sense of the word, but he stubbornly insisted:

Chur! Don't ask, don't complain! Tsits!

Don't whine!

Is it for this reason that commoners

The dry boots trampled, so that I would now betray them?

We'll die like foot soldiers

But we will not glorify either robbery, day labor, or lies!

However, it is in vain to look for a uniform attitude towards the events of 17 in Mandelstam’s poetry. And in general, certain political opinions are rare among poets: they perceive reality too much in their own way, with a special flair. Mandelstam considered inconsistency an indispensable property of lyrics.

Between 1917 and 1925, we can hear several contradictory voices in Mandelstam’s poetry: here are fatal premonitions, and a courageous acceptance of the “creaky steering wheel,” and an increasingly painful longing for a bygone time and a golden age.

In the first poem, inspired by the February events, Mandelstam resorts to a historical symbol: a collective portrait of a Decembrist, combining the features of an ancient hero, a German romantic and a Russian gentleman, undoubtedly a tribute to the bloodless revolution:

The pagan Senate testifies to this -

These things don't die.

But concern for the future is already creeping in:

About the sweet liberty of citizenship!

But the blind skies do not want victims:

Or rather, work and consistency.

This uneasy feeling was destined to soon be justified. The death of the Socialist-Revolutionary Commissar Linde, killed by a crowd of rebellious Cossacks, inspired Mandelstam to write angry poems, where the “October temporary worker” Lenin, preparing the “yoke of violence and malice,” is contrasted with the images of pure heroes - Kerensky (Like Christ!) and Linde, “a free citizen, which was led by Psyche."

And if for others the enthusiastic people

Knocks down golden wreaths -

To bless you will descend to a distant hell

Russia is like pillars of light.

Akhmatova, unlike most poets, was not for a moment seduced by the intoxication of freedom: behind the “cheerful, fiery March” (Z. Gippius), she foresaw the fatal outcome of the summer’s hangover. Addressing modern Kasandra, Mandelstam exclaims:

And in December of the seventeenth year

We lost everything, loving... -

And, in turn, becoming a herald of disasters, he predicts the future tragic fate of the “cheerful sinner of Tsarskoye Selo”:

Someday in the small capital,

At a Scythian festival, on the banks of the Neva,

At the sounds of a disgusting ball

They will tear the scarf from her beautiful head.

Mandelstam refuses a passive perception of the revolution: he seems to give consent to it, but without illusions. Political tone - however, with Mandelstam it always changes. Lenin is no longer an “October temporary worker”, but a “people’s leader who, in tears, takes upon himself the fatal burden” of power. The ode serves as a continuation of the cry over St. Petersburg; it reproduces the dynamic image of a ship going to the bottom, but also responds to it. Following the example of Pushkin’s “Feast during the Plague,” the poet builds his poem on the contrast of unthinkable glorification:

Let us glorify, brothers, the twilight of freedom, -

The Great Twilight Year.

Let us glorify the authorities for the twilight burden,

Her unbearable oppression.

The unglorified is glorified. The rising sun is invisible: it is hidden by swallows bound “in fighting legions”; “the forest is shadowed” means the abolition of freedoms. The central image of the “ship of time” is dual, it is sinking while the earth continues to float. Mandelstam accepts “a huge, clumsy, creaky turn of the steering wheel” out of “compassion for the state,” as he will later explain, out of solidarity with this land, when its salvation would cost “ten heavens.”

Despite this duality and ambiguity, the ode introduces a new dimension to Russian poetry: an active attitude towards the world, regardless of political attitude.

Having brought this calculation together over time, he falls silent: after “January 1” - four poems in two years, and then five years of silence. He switches to prose: in 1925 the memoirs “The Noise of Time” and “Theodosius” appear (also settling scores with time), in 1928 - the story “The Egyptian Stamp”. The style of this prose continues the style of poetry: the same frequency, the same maximum figurative load of each word.

Since 1924, the poet has lived in Leningrad, since 1928 - in Moscow. I have to make a living from translations: 19 books in 6 years, not counting editing. Trying to escape from this debilitating work, he goes to work for the newspaper Moskovsky Komsomolets. But it turns out to be even harder.

With his return to poetry, Mandelstam regained his sense of personal significance. In the winter of 1932-33, several of his author’s evenings took place, the “old intelligentsia” received him with honor; Pasternak said: “I envy your freedom.” Over the course of ten years, Osip Emilievich grew very old and seemed to young listeners to be a “gray-bearded patriarch.” With the help of Bukharin, he receives a pension and enters into an agreement for a two-volume collected works (which was never published).

But this only emphasized its incompatibility with the totalitarian regime in literature. A rare piece of luck - getting an apartment - gives him an impulse to Nekrasov's rebellion, because apartments are given only to opportunists. His nerves are all tense, in his poems he collides with “I want to live until I die” and “I don’t know why I live”, he says: “now every poem is written as if tomorrow is death.” But he remembers: the death of an artist is “the highest act of his creativity,” he once wrote about this in “Scriabin and Christianity.” The impetus was the confluence of three circumstances in 1933. In the summer in Old Crimea, he saw a pestilence, a consequence of collectivization, and this stirred up the Socialist Revolutionary's love for the people.

Now, in November 1933, Osip Mandelstam wrote a small but brave poem, which began his martyrdom through exile and camps.

We live without feeling the country beneath us,

Our speeches are not heard ten steps away,

And where is enough for half a conversation, -

The Kremlin highlander will be remembered there

His thick fingers are like worms, fat

And the words are as true as weights.

The cockroaches are laughing,

And his boots shine.

And around him is a rabble of thin-necked leaders,

He plays with the services of demihumans.

Who whistles, who meows, who whines,

He's the only one who babbles and pokes.

Like a horseshoe bush behind a decree -

Some in the groin, some in the forehead, some in the eyebrow, some in the eye.

No matter what his punishment is, it’s a raspberry

And a broad Ossetian chest.

He reads this epigram on Stalin in great secrecy to no less than fourteen people. “This is suicide,” Pasternak told him, and he was right. It was a voluntary choice of death. Anna Akhmatova remembered for the rest of her life how Mandelstam soon after told her: “I am ready for death.” On the night of May 13-14, Osip Emilievich was arrested.

The poet's friends and relatives realized that there was nothing to hope for. Osip Mandelstam said that from the moment of his arrest he was constantly preparing for execution: “After all, this happens with us on lesser occasions.” The investigator directly threatened to shoot not only him, but all his accomplices. (That is, to those to whom Mandelstam read the poem).

And suddenly a miracle happened.

Not only was Mandelstam not shot, but he wasn’t even sent “to the canal.” He got off with a relatively easy exile to Cherdyn, where his wife was allowed to go with him. And soon this link was canceled. The Mandelstams were allowed to settle anywhere except the twelve largest cities. Osip Emilievich and Nadezhda Konstantinovna named Voronezh at random.

The reason for the “miracle” was Stalin’s phrase: “Isolate, but preserve.”

Nadezhda Yakovlevna believes that Bukharin’s efforts had an effect here. Having received a note from Bukharin, Stalin called Pasternak. Stalin wanted to get from him a qualified opinion about the real value of the poet Osip Mandelstam. He wanted to know how Mandelstam was listed on the poetry exchange, how he was valued in his professional environment.

Mandelstam tells his wife: “Poetry is respected only here. People kill for it. Only here. Nowhere else...”

Stalin's respect for poets was manifested not only in the fact that poets were killed. He understood perfectly well that his descendants’ opinion of him would largely depend on what poets wrote about him.

Having learned that Mandelstam was considered a major poet, he decided not to kill him for the time being. He understood that killing the poet could not stop the effect of poetry. Killing a poet is nothing. Stalin was smarter. He wanted to force Mandelstam to write other poems. Poems exalting Stalin.

Many poets wrote poems glorifying Stalin. But Stalin needed Mandelstam to sing his praises.

Because Mandelstam was a “stranger”. The opinion of “strangers” was very high for Stalin. Being himself a failed poet, in this area Stalin was especially willing to listen to the opinion of authorities. It was not for nothing that he so persistently pestered Pasternak: “But he’s a master, isn’t he? A master?” The answer to this question meant everything to him. A major poet meant a major master. And if the master is, then he will be able to exalt “at the same level of skill” that he exposed.

Mandelstam understood Stalin's intentions. Driven to despair, driven into a corner, he decided to try to save a life at the cost of a few tortured lines. He decided to write the expected “ode to Stalin.”

This is how Nadezhda Yakovlevna recalls this: “At the window in the dressmaker’s room there was a square table that served for everything in the world. Osip, first of all, took possession of the table and laid out poems and paper... For him this was an extraordinary act - after all, he composed poems from his voice and he needed paper only at the very end of his work. Every morning he sat down at the table and picked up a pencil: a writer as a writer¼ But not even half an hour passed before he jumped up and began to curse himself for his lack of skill.”

As a result, the long-awaited “Ode” was born, ending with such a solemn ending:

And six times in my consciousness I shore

Witness of slow labor, struggle and harvest,

His huge path through the taiga

And Lenin's October - until the fulfillment of the oath.

¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼¼

There is no truer truth than the sincerity of a fighter:

For honor and love, for valor and steel.

There is a glorious name for the strong lips of the reader -

We hear him and we caught him.

It would seem that Stalin’s calculations were completely justified. Poems were written. Now Mandelstam could be killed. But Stalin was wrong.

Mandelstam wrote poems glorifying Stalin. Nevertheless, Stalin's plan was a complete failure. To write such poetry, you didn’t have to be Mandelstam. To get such verses, it was not worth playing this whole complex game.

Mandelstam was not a master. He was a poet. He did not weave his poetic fabric from words. He couldn't do that. His poems were woven from a different material.

An involuntary witness to the birth of almost all of his poems (involuntary, because Mandelstam never had so much as an “office”, but not even a kitchenette, a closet where he could retire). Nadezhda Yakovlevna testifies:

“The poems begin like this: in the corners sounds an annoying, at first unformed, and then precise, but still wordless musical phrase. More than once I saw Osip trying to get rid of the prv, shake it off, leave. He shook his head, as if he could throw it out, like a drop of water that fell into my ear while swimming. I got the impression that poems exist before they are composed (Osip Mandelstam never said that poems were “written.” He first “composed”, then wrote them down.) All. the process of composing consists in the intense capture and manifestation of an already existing and, from nowhere, transforming harmonic and semantic unity, gradually embodied in words."

To try to write poetry glorifying Stalin meant for Mandelstam, first of all, to find somewhere at the very bottom of his soul at least some kind of support point for this feeling.

The “Ode” is not entirely dead, faceless lines. There are also those where the attempt at glorification seems to have even been a success:

He hung from the podium as if from a mountain

In the mounds of heads. The debtor is stronger than the claim.

Mighty eyes are decidedly kind,

A thick eyebrow shines close to someone¼

These lines seem alive because an artificial graft of living flesh has been made to their dead island. This tiny piece of living tissue is the phrase “head bumps.” Nadezhda Yakovlevna recalls that, while painfully trying to compose the “Ode,” Mandelstam repeated: “Why, when I think about him, there are all the heads in front of me, mounds of heads? What is he doing with these heads?” Trying with all his might to convince himself that what he was doing to “them” was not what he imagined, but something opposite, i.e. good, Mandelstam involuntarily breaks into a cry:

Mighty eyes are decidedly kind¼

"Ode" was not the only attempt at a forced, artificial glorification of the "father of nations."

In 1937, there, in Voronezh, Mandelstam wrote the poem “If our enemies took me,” ending with the following ending:

And a flock of fiery years will flash by,

Will rustle like a ripe thunderstorm - Lenin,

But on earth that will escape decay,

Stalin will awaken reason and life.

There is a version according to which Mandelstam had a different, opposite in meaning version of the last, ending line:

Will destroy reason and life - Stalin.

There is no doubt that it was this version that reflected the poet’s true understanding of the role in the life of his homeland played by the one whom he had already once called “murderer.”

Of course, Stalin, not without reason, considered himself the greatest expert on issues of “life and death.” He knew that anyone, even the strongest, could be broken. And Mandelstam was not at all one of the strongest.

But Stalin did not know that breaking a person does not mean breaking a poet. He did not know. That it is easier to kill a poet than to force him to sing what is hostile to him. A month passed after Mandelstam’s failed attempt to compose an ode to Stalin. And then something amazing happened - a poem was born:

Among the people's noise and rush

At train stations and squares

A mighty milestone looks through the centuries,

And the eyebrows begin to wave.

I found out, he found out, you found out -

Now take it wherever you want:

Into the talkative jungle of the station,

Waiting by the mighty river.

That parking lot is far away now,

The one with the boiled water -

A tin book on a chain

And darkness covered my eyes.

There was power in the Permian dialect,

Passenger power struggle,

And caressed me and drilled me

From the wall of these eyes there is a lot.

……………………………………

Can't remember what happened -

Lips are hot, words are callous -

The white curtain was breaking,

Carrying the sound of iron leaves.

……………………………………

And to it - to its core -

I entered the Kremlin without a pass,

Tearing apart the canvas of distances,

The guilty head is heavy.

They differ like heaven from earth from those official-glorifying rhymed lines that Mandelstam so difficultly squeezed out of himself, envying Aseev, who, unlike him, was a “master.”

This time the poems came out completely different: burning with sincerity, the certainty of the feelings expressed in them.

Was Stalin really right in his assumptions? Did he really know better than anyone else the extent of the strength of the human soul and had every reason not to doubt the results of his experiment?

Having decided not to shoot Mandelstam for the time being, ordering him to “isolate but preserve”, Stalin, of course, did not know about any artificial clouding of some sources of harmony unknown to him.

In order for his attempt to glorify Stalin to succeed, a poet like Mandelstam could only have one way: this attempt had to be sincere. For Mandelstam, the fulcrum for a more or less sincere attempt at reconciliation with the reality of the Stalinist regime could be only one feeling: hope.

If it were only hope for changes in his personal destiny, there would still be no self-deception. But, by the very nature of his soul, concerned not only with his personal fate, the poet tries to express certain social hopes. And this is where self-deception and self-persuasion begin.

Once upon a time (in an article in 1913) Mandelstam wrote that a poet should under no circumstances make excuses. This, he said, “... is unforgivable! Inadmissible for a poet! The only thing that cannot be forgiven! After all, poetry is the consciousness of one’s rightness.” O. Mandelstam openly proclaimed his readiness to accept the crown of martyrdom “for the explosive valor of the coming centuries, for the high tribe of people.” He demonstratively glorified everything that he never had, just to confirm his innocence, his fully realized hostility to the “wolfhound century.”