Nikolai Karamzin - poor Lisa. Analysis of the story “Poor Liza” (N

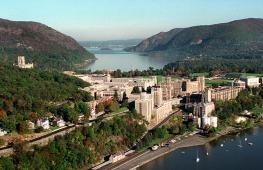

Maybe no one living in Moscow knows the surroundings of this city as well as I do, because no one is in the field more often than I am, no one more than me wanders on foot, without a plan, without a goal - wherever the eyes look - through the meadows and groves , over hills and plains. Every summer I find new pleasant places or new beauty in old ones. But the most pleasant place for me is the place where the gloomy, Gothic towers of the Sin...nova Monastery rise. Standing on this mountain, you see on the right side almost the whole of Moscow, this terrible mass of houses and churches, which appears to the eye in the form of a majestic amphitheater: a magnificent picture, especially when the sun shines on it, when its evening rays glow on countless golden domes, on countless crosses ascending to the sky! Below are lush, densely green flowering meadows, and behind them, along the yellow sands, flows a bright river, agitated by the light oars of fishing boats or rustling under the helm of heavy plows that sail from the most fertile countries of the Russian Empire and supply greedy Moscow with bread.

On the other side of the river one can see an oak grove, near which numerous herds graze; there young shepherds, sitting under the shade of trees, sing simple, sad songs and thus shorten the summer days, so uniform for them. Further away, in the dense greenery of ancient elms, the golden-domed Danilov Monastery shines; even further, almost at the edge of the horizon, the Sparrow Hills are blue. On the left side you can see vast fields covered with grain, forests, three or four villages and in the distance the village of Kolomenskoye with its high palace.

I often come to this place and almost always see spring there; I come there and grieve with nature on the dark days of autumn. The winds howl terribly within the walls of the deserted monastery, between the coffins overgrown with tall grass, and in the dark passages of the cells. There, leaning on the ruins of tombstones, I listen to the dull groan of times, swallowed up by the abyss of the past - a groan from which my heart shudders and trembles. Sometimes I enter cells and imagine those who lived in them - sad pictures! Here I see a gray-haired old man, kneeling before the crucifix and praying for a quick release from his earthly shackles, for all the pleasures in life had disappeared for him, all his feelings had died, except for the feeling of illness and weakness. There a young monk - with a pale face, with a languid gaze - looks into the field through the lattice of the window, sees cheerful birds swimming freely in the sea of air, sees - and sheds bitter tears from his eyes. He languishes, withers, dries up - and the sad ringing of a bell announces to me his untimely death. Sometimes on the gates of the temple I look at the image of miracles that happened in this monastery, where fish fall from the sky to feed the inhabitants of the monastery, besieged by numerous enemies; here the image of the Mother of God puts the enemies to flight. All this renews in my memory the history of our fatherland - the sad history of those times when the ferocious Tatars and Lithuanians devastated the environs of the Russian capital with fire and sword and when unfortunate Moscow, like a defenseless widow, expected help from God alone in its cruel disasters.

But most often what attracts me to the walls of the Sin...nova Monastery is the memory of the deplorable fate of Lisa, poor Lisa. Oh! I love those objects that touch my heart and make me shed tears of tender sorrow!

Seventy yards from the monastery wall, near a birch grove, in the middle of a green meadow, there stands an empty hut, without doors, without endings, without a floor; the roof had long since rotted and collapsed. In this hut, thirty years before, the beautiful, amiable Liza lived with her old woman, her mother.

Lizin's father was a fairly prosperous villager, because he loved work, plowed the land well and always led a sober life. But soon after his death, his wife and daughter became poor. The lazy hand of the mercenary poorly cultivated the field, and the grain ceased to be produced well. They were forced to rent out their land, and for very little money. Moreover, the poor widow, almost constantly shedding tears over the death of her husband - for even peasant women know how to love! – day by day she became weaker and could not work at all. Only Lisa, who remained after her father for fifteen years, - only Lisa, not sparing her tender youth, not sparing her rare beauty, worked day and night - weaving canvases, knitting stockings, picking flowers in the spring, and taking berries in the summer - and selling them in Moscow. The sensitive, kind old woman, seeing her daughter’s tirelessness, often pressed her to her weakly beating heart, called her divine mercy, nurse, the joy of her old age, and prayed to God to reward her for all that she does for her mother.

“God gave me hands to work with,” said Lisa, “you fed me with your breasts and followed me when I was a child; now it’s my turn to follow you. Just stop being upset, stop crying; our tears will not revive the priests.” .

But often tender Liza could not hold back her own tears - ah! she remembered that she had a father and that he was gone, but to reassure her mother she tried to hide the sadness of her heart and seem calm and cheerful. “In the next world, dear Liza,” answered the sad old woman, “in the next world I will stop crying. There, they say, everyone will be cheerful; I’ll probably be cheerful when I see your father. Only now I don’t want to die - what’s wrong with you?” "What will happen without me? Who will leave you with? No, God grant that first you will be settled in a place! Perhaps a good person will soon be found. Then, having blessed you, my dear children, I will cross myself and calmly lie down in the damp earth."

Two years have passed since the death of Lizin's father. The meadows were covered with flowers, and Lisa came to Moscow with lilies of the valley. A young, well-dressed, pleasant-looking man met her on the street. She showed him the flowers and blushed. "Are you selling them, girl?" – he asked with a smile. “I’m selling,” she answered. "What do you need?" - “Five kopecks.” - “It’s too cheap. Here’s a ruble for you.”

Lisa was surprised, she dared to look at the young man, she blushed even more and, looking down at the ground, told him that she would not take the ruble. “For what?” – “I don’t need anything extra.” - “I think that beautiful lilies of the valley, plucked by the hands of a beautiful girl, are worth a ruble. When you don’t take it, here’s five kopecks for you. I would like to always buy flowers from you; I would like you to pick them just for me.” Lisa gave the flowers, took five kopecks, bowed and wanted to go, but the stranger stopped her by the hand: “Where are you going, girl?” - “Home.” - “Where is your house?” Lisa said where she lived, said and went. The young man did not want to hold her, perhaps so that those passing by began to stop and, looking at them, grinned insidiously.

When Lisa came home, she told her mother what had happened to her. “You did well not to take the ruble. Maybe it was some bad person...” - “Oh no, mother! I don’t think so. He has such a kind face, such a voice...” - “ However, Liza, it’s better to feed yourself by your labors and not take anything for nothing. You still don’t know, my friend, how evil people can offend a poor girl! My heart is always in the wrong place when you go to town; I always bet I put a candle in front of the image and I pray to the Lord God that He will protect you from all trouble and adversity.” Tears welled up in Lisa's eyes; she kissed her mother.

The next day Lisa picked the best lilies of the valley and again went into town with them. Her eyes were quietly searching for something.

Many wanted to buy flowers from her, but she replied that they were not for sale, and looked first in one direction or the other. Evening came, it was time to return home, and the flowers were thrown into the Moscow River. "Nobody owns you!" - said Lisa, feeling some kind of sadness in her heart.

The next day in the evening she was sitting under the window, spinning and singing plaintive songs in a quiet voice, but suddenly she jumped up and shouted: “Ah!..” A young stranger stood under the window.

"What happened to you?" – asked the frightened mother, who was sitting next to her. “Nothing, mother,” answered Lisa in a timid voice, “I just saw him.” - "Whom?" - “The gentleman who bought flowers from me.” The old woman looked out the window.

The young man bowed to her so courteously, with such a pleasant air, that she could not think anything but good things about him. “Hello, good old lady!” he said. “I’m very tired; do you have any fresh milk?”

The helpful Liza, without waiting for an answer from her mother - perhaps because she knew it in advance - ran to the cellar - brought a clean jar covered with a clean wooden mug - grabbed a glass, washed it, wiped it with a white towel, poured it and served it out the window, but she was looking at the ground. The stranger drank - and the nectar from Hebe’s hands could not have seemed tastier to him. Everyone will guess that after that he thanked Lisa, and thanked her not so much with words as with his eyes.

Meanwhile, the good-natured old woman managed to tell him about her grief and consolation - about the death of her husband and about the sweet qualities of her daughter, about her hard work and tenderness, and so on. and so on. He listened to her with attention, but his eyes were - need I say where? And Liza, timid Liza, glanced occasionally at the young man; but not so quickly the lightning flashes and disappears in the cloud, as quickly her blue eyes turn to the ground, meeting his gaze. “I would like,” he said to his mother, “for your daughter not to sell her work to anyone but me. Thus, she will have no need to go to the city often, and you will not be forced to part with her. I myself can sometimes come to you." Here a joy flashed in Liza’s eyes, which she tried in vain to hide; her cheeks glowed like the dawn on a clear summer evening; she looked at her left sleeve and pinched it with her right hand. The old woman willingly accepted this offer, not suspecting any bad intention in it, and assured the stranger that the linen woven by Lisa, and the stockings knitted by Lisa, were excellent and last longer than any others.

It was getting dark, and the young man wanted to go. “What should we call you, kind, gentle master?” - asked the old woman. “My name is Erast,” he answered. “Erast,” said Lisa quietly, “Erast!” She repeated this name five times, as if trying to solidify it. Erast said goodbye to them and left. Lisa followed him with her eyes, and the mother sat thoughtfully and, taking her daughter by the hand, said to her: “Oh, Lisa! How good and kind he is! If only your groom were like that!” Liza's heart began to tremble. “Mother! Mother! How can this happen? He is a gentleman, and among the peasants...” - Lisa did not finish her speech.

Now the reader should know that this young man, this Erast, was a rather rich nobleman, with a fair mind and a kind heart, kind by nature, but weak and flighty. He led an absent-minded life, thought only about his own pleasure, looked for it in secular amusements, but often did not find it: he was bored and complained about his fate. Lisa's beauty made an impression on his heart at the first meeting. He read novels, idylls, had a fairly vivid imagination and often moved mentally to those times (former or not), in which, according to the poets, all people carelessly walked through the meadows, bathed in clean springs, kissed like turtle doves, rested under They spent all their days with roses and myrtles and in happy idleness. It seemed to him that he had found in Lisa what his heart had been looking for for a long time. “Nature calls me into its arms, to its pure joys,” he thought and decided - at least for a while - to leave the big world.

Let's turn to Lisa. Night came - the mother blessed her daughter and wished her a gentle sleep, but this time her wish was not fulfilled: Lisa slept very poorly. The new guest of her soul, the image of the Erasts, appeared so vividly to her that she woke up almost every minute, woke up and sighed. Even before the sun rose, Lisa got up, went down to the bank of the Moscow River, sat down on the grass and, saddened, looked at the white mists that were agitated in the air and, rising up, left shiny drops on the green cover of nature. Silence reigned everywhere. But soon the rising luminary of the day awakened all creation: the groves and bushes came to life, the birds fluttered and sang, the flowers raised their heads to drink in the life-giving rays of light. But Lisa still sat there, saddened. Oh, Lisa, Lisa! What happened to you? Until now, waking up with the birds, you had fun with them in the morning, and a pure, joyful soul shone in your eyes, like the sun shines in drops of heavenly dew; but now you are thoughtful, and the general joy of nature is alien to your heart. “Meanwhile, a young shepherd was driving his flock along the river bank, playing the pipe. Lisa fixed her gaze on him and thought: “If the one who now occupies my thoughts was born a simple peasant, a shepherd, - and if he were now driving his flock past me: ah! I would bow to him with a smile and say friendly: “Hello, dear shepherd! Where are you driving your flock? And here green grass grows for your sheep, and here flowers grow red, from which you can weave a wreath for your hat." He would look at me with a gentle look - he would perhaps take my hand... A dream!" A shepherd, playing the flute, passed by and disappeared with his motley flock behind a nearby hill.

Suddenly Lisa heard the sound of oars - she looked at the river and saw a boat, and in the boat - Erast.

All the veins in her were clogged, and, of course, not from fear. She got up and wanted to go, but she couldn’t. Erast jumped out onto the shore, approached Lisa and - her dream was partly fulfilled: for he looked at her with an affectionate look, took her hand... But Lisa, Lisa stood with downcast eyes, with fiery cheeks, with a trembling heart - she could not take his hands away, she couldn’t turn away when he approached her with his pink lips... Ah! He kissed her, kissed her with such fervor that the whole universe seemed to her to be on fire! “Dear Liza!” said Erast. “Dear Liza! I love you!”, and these words echoed in the depths of her soul like heavenly, delightful music; she hardly dared to believe her ears and...

But I throw down the brush. I will only say that at that moment of delight Liza’s timidity disappeared - Erast learned that he was loved, loved passionately with a new, pure, open heart.

They sat on the grass, and so that there was not much space between them, they looked into each other’s eyes, said to each other: “Love me!”, and two hours seemed to them like an instant. Finally Lisa remembered that her mother might worry about her. It was necessary to separate. “Oh, Erast!” she said. “Will you always love me?” - “Always, dear Lisa, always!” - he answered. “And can you swear to me this?” - “I can, dear Lisa, I can!” - “No! I don’t need an oath. I believe you, Erast, I believe you. Are you really going to deceive poor Liza? Surely this cannot be?” - “You can’t, you can’t, dear Lisa!” - “How happy I am, and how happy mother will be when she finds out that you love me!” - “Oh no, Lisa! She doesn’t need to say anything.” - “For what?” - “Old people can be suspicious. She will imagine something bad.” - “It can’t happen.” - “However, I ask you not to say a word to her about this.” - “Okay: I need to listen to you, although I wouldn’t want to hide anything from her.”

They said goodbye, kissed for the last time and promised to see each other every day in the evening, either on the river bank, or in a birch grove, or somewhere near Liza’s hut, just to be sure, to see each other without fail. Lisa went, but her eyes turned a hundred times to Erast, who was still standing on the shore and looking after her.

Lisa returned to her hut in a completely different state than in which she left it. Heartfelt joy was revealed on her face and in all her movements. "He loves me!" - she thought and admired this thought. “Oh, mother!” Liza said to her mother, who had just woken up. “Oh, mother! What a wonderful morning! How fun everything is in the field! Never have the larks sung so well, never has the sun shone so brightly, never have the flowers been so pleasant smelled!" The old woman, propped up with a stick, went out into the meadow to enjoy the morning, which Lisa described in such lovely colors. It really seemed to her extremely pleasant; the kind daughter cheered up her whole nature with her joy. “Oh, Liza!” she said. “How good everything is with the Lord God! I’m sixty years old in this world, and I still can’t get enough of God’s works, I can’t get enough of the clear sky, like a high tent, and the earth, which Every year it is covered with new grass and new flowers. The king of heaven must love a person very much when he has taken away the local light so well for him. Oh, Liza! Who would want to die if sometimes we didn’t have grief?.. Apparently, so necessary. Maybe we would forget our souls if tears never fell from our eyes." And Lisa thought: “Ah! I would sooner forget my soul than my dear friend!”

After this, Erast and Liza, fearing not to keep their word, saw each other every evening (while Liza’s mother went to bed) either on the river bank, or in a birch grove, but most often under the shade of hundred-year-old oak trees (eighty fathoms from the hut) - oaks , overshadowing a deep, clear pond, fossilized in ancient times. There, the often quiet moon, through the green branches, silvered Liza’s blond hair with its rays, with which the zephyrs and the hand of a dear friend played; often these rays illuminated in the eyes of tender Liza a brilliant tear of love, always dried with Erast’s kiss. They hugged - but chaste, bashful Cynthia did not hide from them behind a cloud: their embrace was pure and immaculate. “When you,” said Lisa to Erast, “when you tell me: “I love you, my friend!”, when you press me to your heart and look at me with your touching eyes, ah! then it happens to me so good, so good that I forget myself, I forget everything except Erast. It’s wonderful! It’s wonderful, my friend, that without knowing you, I could live calmly and cheerfully! Now I don’t understand it, now I think that without you life is not life, but sadness and boredom. Without your eyes the bright moon is dark; without your voice the singing nightingale is boring; without your breath the breeze is unpleasant to me." Erast admired his shepherdess—that’s what he called Lisa—and, seeing how much she loved him, he seemed more kind to himself. All the brilliant amusements of the great world seemed insignificant to him in comparison with the pleasures with which the passionate friendship of an innocent soul nourished his heart. With disgust he thought about the contemptuous voluptuousness with which his feelings had previously reveled. “I will live with Liza, like brother and sister,” he thought, “I will not use her love for evil and I will always be happy!” Reckless young man! Do you know your heart? Can you always be responsible for your movements? Is reason always the king of your feelings?

Lisa demanded that Erast often visit her mother. “I love her,” she said, “and I want the best for her, but it seems to me that seeing you is a great blessing for everyone.” The old lady was really always happy when she saw him. She loved to talk with him about her late husband and tell him about the days of her youth, about how she first met her dear Ivan, how he fell in love with her and in what love, in what harmony he lived with her. “Ah! We could never look at each other enough - until that very hour when cruel death crushed his legs. He died in my arms!” Erast listened to her with unfeigned pleasure. He bought Liza’s work from her and always wanted to pay ten times more than the price she set, but the old woman never took extra.

Several weeks passed in this way. One evening Erast waited a long time for his Lisa. Finally she came, but she was so sad that he was afraid; her eyes turned red from tears. "Lisa, Liza! What happened to you?" - “Oh, Erast! I cried!” - “About what? What is it?” - “I have to tell you everything. The groom, the son of a rich peasant from a neighboring village, is wooing me; my mother wants me to marry him.” - “And you agree?” - “Cruel! Can you ask about this? Yes, I feel sorry for mother; she cries and says that I don’t want her peace of mind, that she will suffer at death if she doesn’t marry me off with her. Ah! Mother doesn’t know that I have such a sweet friend!" Erast kissed Lisa and said that her happiness was dearer to him than anything in the world, that after her mother’s death he would take her to him and live with her inseparably, in the village and in the dense forests, as if in paradise. “However, you can’t be my husband!” – Lisa said with a quiet sigh. "Why?" - “I am a peasant woman.” - “You offend me. For your friend, the most important thing is the soul, the sensitive, innocent soul - and Lisa will always be closest to my heart.”

She threw herself into his arms - and at this hour her integrity had to perish! Erast felt an extraordinary excitement in his blood - Liza had never seemed so charming to him - never had her caresses touched him so much - never had her kisses been so fiery - she knew nothing, suspected nothing, was afraid of nothing - the darkness of the evening fed desires - not a single star shone in the sky - no ray could illuminate the errors. - Erast feels awe in himself - Lisa also, not knowing why, not knowing what is happening to her... Ah, Lisa, Lisa! Where is your guardian angel? Where is your innocence?

The delusion passed in one minute. Lisa did not understand her feelings, she was surprised and asked. Erast was silent - he searched for words and did not find them. “Oh, I’m afraid,” said Lisa, “I’m afraid of what happened to us! It seemed to me that I was dying, that my soul... No, I don’t know how to say it!.. Are you silent, Erast? Are you sighing?.. "Oh my God! What is it?" Meanwhile, lightning flashed and thunder roared. Lisa trembled all over. “Erast, Erast!” she said. “I’m scared! I’m afraid that the thunder will kill me like a criminal!” The storm roared menacingly, rain poured from black clouds - it seemed that nature was lamenting about Liza’s lost innocence. Erast tried to calm Lisa down and walked her to the hut. Tears rolled from her eyes as she said goodbye to him. “Oh, Erast! Assure me that we will continue to be happy!” - “We will, Lisa, we will!” - he answered. - “God willing! I can’t help but believe your words: I love you! Only in my heart... But that’s enough! Forgive me! Tomorrow, tomorrow I’ll see you.”

Their dates continued; but how everything has changed! Erast could no longer be satisfied with just the innocent caresses of his Liza - just her glances filled with love - just one touch of a hand, one kiss, just one pure embrace. He wanted more, more, and finally could not want anything - and whoever knows his heart, who has reflected on the nature of its most tender pleasures, will, of course, agree with me that the fulfillment of all desires is the most dangerous temptation of love. For Erast, Lisa was no longer that angel of purity that had previously inflamed his imagination and delighted his soul. Platonic love gave way to feelings of which he could not be proud and which were no longer new to him. As for Lisa, she, completely surrendering to him, only lived and breathed him, in everything, like a lamb, she obeyed his will and placed her happiness in his pleasure. She saw a change in him and often told him: “Before you were more cheerful, before we were calmer and happier, and before I was not so afraid of losing your love!” Sometimes, saying goodbye to her, he told her: “Tomorrow, Liza, I can’t see you: I have an important matter,” and every time at these words Liza sighed.

Finally, for five days in a row she did not see him and was in the greatest anxiety; on the sixth day he came with a sad face and said: “Dear Liza! I must say goodbye to you for a while. You know that we are at war, I am in the service, my regiment is going on a campaign.” Lisa turned pale and almost fainted.

Erast caressed her, said that he would always love dear Liza and hoped that upon his return he would never part with her. She was silent for a long time, then burst into bitter tears, grabbed his hand and, looking at him with all the tenderness of love, asked: “Can’t you stay?” “I can,” he answered, “but only with the greatest dishonor, with the greatest stain on my honor. Everyone will despise me; everyone will abhor me as a coward, as an unworthy son of the fatherland.” “Oh, when that’s the case,” said Lisa, “then go, go wherever God tells you! But they can kill you.” - “Death for the fatherland is not terrible, dear Liza.” - “I will die as soon as you are no longer in the world.” - “But why think about it? I hope to stay alive, I hope to return to you, my friend.” - “God willing! God willing! Every day, every hour I will pray about it. Oh, why can’t I read or write. You would notify me about everything that happens to you, and I would write to you - about your tears!" - “No, take care of yourself, Lisa, take care of your friend. I don’t want you to cry without me.” - “Cruel man! You think to deprive me of this joy! No! Having parted with you, will I stop crying when my heart dries up.” - “Think about the pleasant moment in which we will see each other again.” - “I will, I will think about her! Oh, if only she would come sooner! Dear, dear Erast! Remember, remember your poor Liza, who loves you more than herself!”

But I cannot describe everything that they said on this occasion. The next day was supposed to be the last date.

Erast also wanted to say goodbye to Liza’s mother, who could not hold back tears when she heard that her affectionate, handsome master was about to go to war. He forced her to take some money from him, saying: “I don’t want Lisa to sell her work in my absence, which, by agreement, belongs to me.” The old lady showered him with blessings. “God grant,” she said, “that you return to us safely and that I see you once again in this life! Perhaps by that time my Lisa will find a groom according to her thoughts. How I would thank God if you came for our wedding! When Lisa has children, know, master, that you must baptize them! Oh! I would really like to live to see this! " Lisa stood next to her mother and did not dare look at her. The reader can easily imagine what she felt at that moment.

But what did she feel then when Erast, hugging her for the last time, pressing her to his heart for the last time, said: “Forgive me, Liza!..” What a touching picture! The morning dawn, like a scarlet sea, spread across the eastern sky. Erast stood under the branches of a tall oak tree, holding in his arms his poor, languid, sorrowful friend, who, saying goodbye to him, said goodbye to her soul. The whole nature was silent.

Lisa sobbed - Erast cried - left her - she fell - knelt down, raised her hands to the sky and looked at Erast, who moved away - further - further - and finally disappeared - the sun rose, and Lisa, abandoned, poor, fainted and memory.

She came to her senses - and the light seemed dull and sad to her. All the pleasant things of nature were hidden for her along with those dear to her heart. “Ah!” she thought. “Why did I stay in this desert? What keeps me from flying after dear Erast? War is not scary for me; it’s scary where my friend is not there. I want to live with him, die with him, or die by my own.” "Save his precious life. Wait, wait, my dear! I'm flying to you!" She already wanted to run after Erast, but the thought: “I have a mother!” – stopped her. Lisa sighed and, bowing her head, walked with quiet steps towards her hut. From that hour, her days were days of melancholy and sorrow, which had to be hidden from her tender mother: all the more did her heart suffer! Then it only became easier when Lisa, secluded in the depths of the forest, could freely shed tears and moan about separation from her beloved. Often the sad turtledove combined his plaintive voice with her moaning. But sometimes - although very rarely - a golden ray of hope, a ray of consolation, illuminated the darkness of her sorrow. “When he returns to me, how happy I will be! How everything will change!” From this thought her gaze cleared, the roses on her cheeks were refreshed, and Lisa smiled like a May morning after a stormy night. Thus, about two months passed.

One day Lisa had to go to Moscow to buy rose water, which her mother used to treat her eyes. On one of the big streets she met a magnificent carriage, and in this carriage she saw Erast. "Oh!" – Liza screamed and rushed towards him, but the carriage drove past and turned into the yard. Erast came out and was about to go to the porch of the huge house, when he suddenly felt himself in Lisa’s arms. He turned pale - then, without answering a word to her exclamations, he took her hand, led her into his office, locked the door and said to her: “Lisa! Circumstances have changed; I was engaged to get married; you must leave me alone for your own peace of mind.” forget me. I loved you and now I love you, that is, I wish you every good thing. Here are a hundred rubles—take them,” he put the money in her pocket, “let me kiss you for the last time—and go home.” Before Lisa could come to her senses, he took her out of the office and said to the servant: “Escort this girl from the yard.”

My heart is bleeding at this very moment. I forget the man in Erast - I’m ready to curse him - but my tongue does not move - I look at him, and a tear rolls down my face. Oh! Why am I writing not a novel, but a sad true story?

So, Erast deceived Lisa by telling her that he was going to the army? No, he really was in the army, but instead of fighting the enemy, he played cards and lost almost all his property. Peace was soon concluded, and Erast returned to Moscow, burdened with debts. He had only one way to improve his circumstances - to marry an elderly rich widow who had long been in love with him. He decided to do so and moved to live in her house, dedicating a sincere sigh to his Lisa. But can all this justify him?

Lisa found herself on the street, and in a position that no pen could describe. "He, he kicked me out? Does he love someone else? I'm dead!" - these are her thoughts, her feelings! A severe faint interrupted them for a while. One kind woman who was walking down the street stopped over Liza, who was lying on the ground, and tried to bring her to memory. The unfortunate woman opened her eyes, stood up with the help of this kind woman, thanked her and went, not knowing where. “I can’t live,” thought Lisa, “I can’t!.. Oh, if the sky would fall on me! If the earth would swallow up the poor woman!.. No! The sky doesn’t fall; the earth doesn’t shake! Woe to me!” She left the city and suddenly saw herself on the shore of a deep pond, under the shade of ancient oak trees, which a few weeks before had been silent witnesses to her delight. This memory shook her soul; the most terrible heartache was depicted on her face. But after a few minutes she plunged into some thoughtfulness - she looked around her, saw her neighbor’s daughter (a fifteen-year-old girl) walking along the road - she called her, took ten imperials out of her pocket and, handing them to her, said: “Dear Anyuta, dear friend! Take it to her.” this money to my mother - it is not stolen - tell her that Liza is guilty against her, that I hid from her my love for one cruel man - for E... Why know his name? - Tell me that he cheated on me, - ask her to forgive me, - God will be her helper, kiss her hand the way I kiss yours now, say that poor Lisa ordered me to kiss her, - say that I...” Then she threw herself into the water. Anyuta screamed and cried, but could not save her, she ran to the village - people gathered and pulled Lisa out, but she was already dead.

Thus she ended her life, beautiful in body and soul. When we see each other there, in a new life, I will recognize you, gentle Lisa!

She was buried near a pond, under a gloomy oak tree, and a wooden cross was placed on her grave. Here I often sit in thought, leaning on the receptacle of Liza’s ashes; a pond flows in my eyes; The leaves rustle above me.

Lisa's mother heard about the terrible death of her daughter, and her blood ran cold with horror - her eyes closed forever. The hut was empty. The wind howls in it, and the superstitious villagers, hearing this noise at night, say: “There is a dead man moaning there; poor Lisa is moaning there!”

Erast was unhappy until the end of his life. Having learned about Lizina’s fate, he could not console himself and considered himself a murderer. I met him a year before his death. He himself told me this story and led me to Lisa’s grave. Now maybe they have already reconciled!

According to the publication: Karamzin N. M. Selected works: In 2 volumes - M.; L.: Fiction, 1964.

The story “Poor Liza,” which became an example of sentimental prose, was published by Nikolai Mikhailovich Karamzin in 1792 in the Moscow Journal publication. It is worth noting Karamzin as an honored reformer of the Russian language and one of the most highly educated Russians of his time - this is an important aspect that allows us to further evaluate the success of the story. Firstly, the development of Russian literature was of a “catch-up” nature, since it lagged behind European literature by about 90-100 years. While sentimental novels were being written and read in the West, clumsy classical odes and dramas were still being composed in Russia. Karamzin’s progressiveness as a writer consisted in “bringing” sentimental genres from Europe to his homeland and developing a style and language for the further writing of such works.

Secondly, the assimilation of literature by the public at the end of the 18th century was such that at first they wrote for society how to live, and then society began to live according to what was written. That is, before the sentimental story, people read mainly hagiographic or church literature, where there were no living characters or living speech, and the heroes of the sentimental story - such as Lisa - gave secular young ladies a real life scenario, a guide to feelings.

The history of the story

Karamzin brought the story about poor Liza from his many trips - from 1789 to 1790 he visited Germany, England, France, Switzerland (England is considered the birthplace of sentimentalism), and upon his return he published a new revolutionary story in his own magazine.

“Poor Liza” is not an original work, since Karamzin adapted its plot for Russian soil, taking it from European literature. We are not talking about a specific work and plagiarism - there were many such European stories. In addition, the author created an atmosphere of amazing authenticity by depicting himself as one of the heroes of the story and masterfully describing the setting of events.

According to the memoirs of contemporaries, soon after returning from the trip, the writer lived in a dacha near the Simonov Monastery, in a picturesque, calm place. The situation described by the author is real - readers recognized both the surroundings of the monastery and the “Lizin Pond”, and this contributed to the fact that the plot was perceived as reliable, and the characters as real people.

Analysis of the work

Plot of the story

The plot of the story is love and, as the author admits, extremely simple. The peasant girl Lisa (her father was a wealthy peasant, but after his death the farm is in decline and the girl has to earn money by selling handicrafts and flowers) lives in the lap of nature with her old mother. In a city that seems huge and alien to her, she meets a young nobleman, Erast. Young people fall in love - Erast out of boredom, inspired by pleasures and a noble lifestyle, and Liza - for the first time, with all the simple, ardor and naturalness of a “natural person”. Erast takes advantage of the girl’s gullibility and takes possession of her, after which, naturally, he begins to be burdened by the girl’s company. The nobleman leaves for war, where he loses his entire fortune at cards. The way out is to marry a rich widow. Lisa finds out about this and commits suicide by throwing herself into a pond, not far from the Simonov Monastery. The author, who was told this story, cannot remember poor Lisa without holy tears of regret.

Karamzin, for the first time among Russian writers, unleashed the conflict of a work with the death of the heroine - as, most likely, it would have happened in reality.

Of course, despite the progressiveness of Karamzin’s story, his heroes differ significantly from real people, they are idealized and embellished. This is especially true for peasants - Lisa does not look like a peasant woman. It is unlikely that hard work would have contributed to her remaining “sensitive and kind”; it is unlikely that she would conduct internal dialogues with herself in an elegant style, and she would hardly be able to carry on a conversation with a nobleman. Nevertheless, this is the first thesis of the story - “even peasant women know how to love.”

Main characters

Lisa

The central heroine of the story, Lisa, is the embodiment of sensitivity, ardor and ardor. Her intelligence, kindness and tenderness, the author emphasizes, are from nature. Having met Erast, she begins to dream not that he, like a handsome prince, will take her into his world, but that he would be a simple peasant or shepherd - this would equalize them and allow them to be together.

Erast differs from Lisa not only in social terms, but also in character. Perhaps, the author says, he was spoiled by the world - he leads a typical life for an officer and a nobleman - he seeks pleasure and, having found it, grows cold towards life. Erast is both smart and kind, but weak, incapable of action - such a hero also appears in Russian literature for the first time, a type of “aristocrat disillusioned with life.” At first, Erast is sincere in his impulse of love - he does not lie when he tells Lisa about love, and it turns out that he is also a victim of circumstances. He does not stand the test of love, does not resolve the situation “like a man,” but experiences sincere torment after what happened. After all, it was he who allegedly told the author the story about poor Lisa and led him to Lisa’s grave.

Erast predetermined the appearance in Russian literature of a number of heroes of the “superfluous people” type - weak and incapable of making key decisions.

Karamzin uses “speaking names.” In the case of Lisa, the choice of name turned out to be a “double bottom.” The fact is that classical literature provided typification techniques, and the name Lisa was supposed to mean a playful, flirtatious, frivolous character. This name could have been given to a laughing maid - a cunning comedy character, prone to love adventures, and by no means innocent. By choosing such a name for his heroine, Karamzin destroyed the classical typification and created a new one. He built a new relationship between the name, character and actions of the hero and outlined the path to psychologism in literature.

The name Erast was also not chosen by chance. It means “lovely” from Greek. His fatal charm and the need for novelty of impressions lured and destroyed the unfortunate girl. But Erast will reproach himself for the rest of his life.

Constantly reminding the reader of his reaction to what is happening (“I remember with sadness...”, “tears are rolling down my face, reader...”), the author organizes the narrative so that it acquires lyricism and sensitivity.

Quotes

“Mother! Mother! How can this happen? He is a gentleman, but among the peasants...”. Lisa.

“Nature calls me into its arms, to its pure joys,” he thought and decided, at least for a while, to leave the big world.”.

“I can’t live,” thought Lisa, “I can’t!.. Oh, if the sky would fall on me! If the earth would swallow up the poor woman!.. No! the sky doesn’t fall; the earth doesn’t shake! Woe to me.” Lisa.

"Now maybe they have already reconciled!" Author

Theme, conflict of the story

Karamzin's story touches on several topics:

- The theme of the idealization of the peasant environment, the ideality of life in nature. The main character is a child of nature, and therefore by default she cannot be evil, immoral, or insensitive. The girl embodies simplicity and innocence due to the fact that she is from a peasant family, where eternal moral values are kept.

- Theme of love and betrayal. The author glorifies the beauty of sincere feelings and talks with sorrow about the doom of love, not supported by reason.

- The theme is the contrast between countryside and city. The city turns out to be evil, a great evil force capable of breaking a pure being from nature (Lisa’s mother intuitively senses this evil force and prays for her daughter every time she goes to the city to sell flowers or berries).

- Theme "little man". Social inequality, the author is sure (and this is an obvious glimpse of realism) does not lead to happiness for lovers from different backgrounds. This kind of love is doomed.

The main conflict of the story is social, because it is because of the gap between wealth and poverty that the love of the heroes, and then the heroine, perishes. The author extols sensitivity as the highest human value, asserts the cult of feelings as opposed to the cult of reason.

Maybe no one living in Moscow knows the surroundings of this city as well as I do, because no one is in the field more often than I am, no one more than me wanders on foot, without a plan, without a goal - wherever the eyes look - through the meadows and groves , over hills and plains. Every summer I find new pleasant places or new beauty in old ones.

But the most pleasant place for me is the gloomy, Gothic towers of the Si...nova Monastery. Standing on this mountain, you see on the right side almost the whole of Moscow, this terrible mass of houses and churches, which appears to your eyes in the image of a majestic amphitheater: a magnificent picture, especially when the sun shines on it, when its evening rays glow on countless golden domes, on countless crosses ascending to the sky! Below are lush, densely green flowering meadows, and behind them, along the yellow sands, flows a bright river, agitated by the light oars of fishing boats or rustling under the helm of heavy plows that sail from the most fertile countries of the Russian Empire and supply greedy Moscow with bread. On the other side of the river one can see an oak grove, near which numerous herds graze; there young shepherds, sitting under the shade of trees, sing simple, sad songs and thus shorten the summer days, so uniform for them. Further away, in the dense greenery of ancient elms, the golden-domed Danilov Monastery shines; even further, almost at the edge of the horizon, the Sparrow Hills are blue. On the left side you can see vast fields covered with grain, forests, three or four villages and in the distance the village of Kolomenskoye with its high palace.

I often come to this place and almost always see spring there; I come there and grieve with nature on the dark days of autumn. The winds howl terribly within the walls of the deserted monastery, between the coffins overgrown with tall grass, and in the dark passages of the cells. There, leaning on the ruins of tombstones, I listen to the dull groan of times, swallowed up by the abyss of the past - a groan from which my heart shudders and trembles. Sometimes I enter cells and imagine those who lived in them - sad pictures! Here I see a gray-haired old man, kneeling before the crucifix and praying for a quick release from his earthly shackles, for all the pleasures in life had disappeared for him, all his feelings had died, except for the feeling of illness and weakness. There a young monk - with a pale face, with a languid gaze - looks into the field through the lattice of the window, sees cheerful birds swimming freely in the sea of air, sees - and sheds bitter tears from his eyes. He languishes, withers, dries up - and the sad ringing of a bell announces to me his untimely death. Sometimes on the gates of the temple I look at the image of miracles that happened in this monastery, where fish fall from the sky to feed the inhabitants of the monastery, besieged by numerous enemies; here the image of the Mother of God puts the enemies to flight. All this renews in my memory the history of our fatherland - the sad history of those times when the ferocious Tatars and Lithuanians devastated the environs of the Russian capital with fire and sword and when unfortunate Moscow, like a defenseless widow, expected help from God alone in its cruel disasters.

But what most often attracts me to the walls of the Si...nova Monastery is the memory of the deplorable fate of Lisa, poor Lisa. Oh! I love those objects that touch my heart and make me shed tears of tender sorrow!

Seventy yards from the monastery wall, near a birch grove, in the middle of a green meadow, there stands an empty hut, without doors, without endings, without a floor; the roof had long since rotted and collapsed. In this hut, thirty years before, the beautiful, amiable Liza lived with her old woman, her mother.

Lizin's father was a fairly prosperous villager, because he loved work, plowed the land well and always led a sober life. But soon after his death, his wife and daughter became poor. The lazy hand of the mercenary poorly cultivated the field, and the grain ceased to be produced well. They were forced to rent out their land, and for very little money. Moreover, the poor widow, almost constantly shedding tears over the death of her husband - for even peasant women know how to love! – day by day she became weaker and could not work at all. Only Lisa, who remained after her father for fifteen years, only Lisa, not sparing her tender youth, not sparing her rare beauty, worked day and night - weaving canvases, knitting stockings, picking flowers in the spring, and taking berries in the summer - and selling them in Moscow. The sensitive, kind old woman, seeing her daughter’s tirelessness, often pressed her to her weakly beating heart, called her divine mercy, nurse, the joy of her old age, and prayed to God to reward her for all that she does for her mother. “God gave me hands to work with,” said Lisa, “you fed me with your breasts and followed me when I was a child; Now it’s my turn to follow you. Just stop breaking down, stop crying; Our tears will not revive the priests.” But often tender Liza could not hold back her own tears - ah! she remembered that she had a father and that he was gone, but to reassure her mother she tried to hide the sadness of her heart and seem calm and cheerful. “In the next world, dear Liza,” answered the sad old woman, in the next world I will stop crying. There, they say, everyone will be happy; I will probably be happy when I see your father. Only now I don’t want to die - what will happen to you without me? To whom should I leave you? No, God grant that we get you a place first! Maybe a kind person will soon be found. Then, having blessed you, my dear children, I will cross myself and calmly lie down in the damp earth.”

Two years have passed since the death of Lizin's father. The meadows were covered with flowers, and Lisa came to Moscow with lilies of the valley. A young, well-dressed, pleasant-looking man met her on the street. She showed him the flowers and blushed. “Are you selling them, girl?” – he asked with a smile. “I’m selling,” she answered. - “What do you need?” - “Five kopecks.” - “It's too cheap. Here's a ruble for you." - Lisa was surprised, she dared to look at the young man, she blushed even more and, looking down at the ground, told him that she would not take the ruble. - “For what?” - “I don’t need anything extra.” “I think that beautiful lilies of the valley, plucked by the hands of a beautiful girl, are worth a ruble. When you don’t take it, here’s your five kopecks. I would like to always buy flowers from you; I would like you to tear them just for me.” “Lisa gave the flowers, took five kopecks, bowed and wanted to go, but the stranger stopped her by the hand. - “Where are you going, girl?” - “Home.” - “Where is your house?” – Lisa said where she lives, she said and went. The young man did not want to hold her, perhaps because those passing by began to stop and, looking at them, grinned insidiously.

Rated the book

"Poor Lisa"

What a naive story. If in some incomprehensible way you managed to avoid knowledge of the fate of poor Lisa, then from the first lines it is still completely clear what will happen next and why. But do you know what feeling you get when reading? Tenderness. Was there really such naivety, could there really be such love? And one more thing... if Lisa is such a pure and noble girl, how could she doom her mother to a lonely old age? In general, the most interesting thing when reading this story was drawing up in my head the image of an ideal woman according to Karamzin. What is she like? It seemed to me that something like this: love a man with all your heart, trust him in everything, don’t care about everyone else, be innocent, modest, etc. Are there such things? Definitely not Poor Karamzin...

"Natalia, boyar's daughter"

I heard somewhere that when Catherine the Great was brought a newspaper, which, on her orders, was printed in St. Petersburg, she was indignant that journalists were describing what was bad and said something like: “Why do you write only about bad things? I already know what’s wrong with us. You’d better write what’s good about us!” I can’t vouch for the accuracy of the quote, but I conveyed the meaning correctly. We won’t talk about the literalness of the perception of her words, and several centuries later we won’t talk now, and it’s not so clear, let’s talk about something else. Karamzin writes about good things. Firstly: the whole story is simply permeated with love for Russia, faith in the Tsar, longing for real and specifically Russian people. Secondly: the images of the heroes of the story are so ideal that it is difficult to believe in the reality of their existence, and it is not necessary. Thirdly: faith in justice and in pure, eternal love is a leitmotif that, despite all the fabulousness, captivates even a very cynical modern writer. It seems to me that this story by Karamzin should be perceived as a fairy tale, and a fairy tale, as we know, should not be believable, much less real. She should just be kind and talk about something good (having a princess and a prince, whoever they are, is a must).

"Martha the Posadnitsa"

Wild peoples love independence, wise peoples love order, and there is no order without autocratic power

And the people of free Novgorod could listen to the royal messenger, but they liked listening more to a woman offended by fate. And offended, and especially lonely women, are bad advisers. Thanks to the advice of the “freedom-loving” Madame Marfa, she was not the only one who became lonely; almost all the women of Veliky Novgorod added to her loneliness, and all together it was no longer so sad. Hmm... When the free inhabitants starved, fought with the royal army and drank hard, they became uninterested in free life and they joyfully greeted Ivan the Terrible, who decided on this very Martha and her daughter (apparently for sure). So, no matter how you look at it, all roads lead to autocracy, no matter how formidable it may be.

Rated the book

About "Martha the Posadnitsa..."

And I liked this “fairy tale,” especially after we examined this work from different points of view during lectures on the history of Russian culture.

In my opinion, this historical story has every chance of success, so to speak - it is interesting, very dynamic, and the language is quite digestible even for a modern reader. However, there is a significant drawback (which, of course, should be written down not for Karamzin, but for the modern reader) - anyone who wants to get acquainted with “Martha the Posadnitsa” must become familiar with real historical events. After this, reading will become even more interesting, because comparing reality and fiction is always interesting, especially if the author does not position his work as a purely historical chronicle.

In addition, in addition to the historical action, Karamzin’s point of view on various aspects of life (wealth, for example) is also interesting.

Plus, this story is purely oppositional for its time, which also cannot leave anyone indifferent. Karamzin's idea that the only correct form of government for Russia is autocracy cannot fail to attract the attention of an enlightened and interested public. (5/5)

About "Poor Lisa".

To understand and perceive this work without an aching jaw and exclamations of “God, what an idiot,” you need to be a man of your time. I'm terribly sentimental, but this piece gave me a creepy reaction. Precisely because I live in a different time, which means I simply cannot understand many of the actions and thoughts of those times. Romanticism - yes, but not sentimentalism. (2/5)

Karamzin N M

Poor Lisa

Perhaps no one living in Moscow knows the surroundings of this city as well as I do, because no one is in the field more often than me, no one more than me wanders on foot, without a plan, without a goal - wherever the eyes look - through the meadows and groves , over hills and plains. Every summer I find new pleasant places or new beauty in old ones. But the most pleasant place for me is the place where the gloomy, Gothic towers of the Si...nova Monastery rise. Standing on this mountain, you see on the right side almost the whole of Moscow, this terrible mass of houses and churches, which appears to the eye in the form of a majestic amphitheater: a magnificent picture, especially when the sun shines on it, when its evening rays glow on countless golden domes, on countless crosses ascending to the sky! Below are lush, densely green flowering meadows, and behind them, along the yellow sands, flows a bright river, agitated by the light oars of fishing boats or rustling under the helm of heavy plows that sail from the most fertile countries of the Russian Empire and supply greedy Moscow with bread.

On the other side of the river one can see an oak grove, near which numerous herds graze; there young shepherds, sitting under the shade of trees, sing simple, sad songs and thus shorten the summer days, so uniform for them. Further away, in the dense greenery of ancient elms, the golden-domed Danilov Monastery shines; even further, almost at the edge of the horizon, the Sparrow Hills are blue. On the left side you can see vast fields covered with grain, forests, three or four villages and in the distance the village of Kolomenskoye with its high palace.

I often come to this place and almost always see spring there; I come there and grieve with nature on the dark days of autumn. The winds howl terribly within the walls of the deserted monastery, between the coffins overgrown with tall grass, and in the dark passages of the cells. There, leaning on the ruins of tombstones, I listen to the dull groan of times, swallowed up by the abyss of the past - a groan from which my heart shudders and trembles. Sometimes I enter cells and imagine those who lived in them - sad pictures! Here I see a gray-haired old man, kneeling before the crucifix and praying for a quick release from his earthly shackles, for all the pleasures in life had disappeared for him, all his feelings had died, except for the feeling of illness and weakness. There a young monk - with a pale face, with a languid gaze - looks into the field through the lattice of the window, sees cheerful birds swimming freely in the sea of air, sees - and sheds bitter tears from his eyes. He languishes, withers, dries up - and the sad ringing of a bell announces to me his untimely death. Sometimes on the gates of the temple I look at the image of miracles that happened in this monastery, where fish fall from the sky to feed the inhabitants of the monastery, besieged by numerous enemies; here the image of the Mother of God puts the enemies to flight. All this renews in my memory the history of our fatherland - the sad history of those times when the ferocious Tatars and Lithuanians devastated the environs of the Russian capital with fire and sword and when unfortunate Moscow, like a defenseless widow, expected help from God alone in its cruel disasters.

But most often what attracts me to the walls of the Si...nova Monastery is the memory of the deplorable fate of Lisa, poor Lisa. Oh! I love those objects that touch my heart and make me shed tears of tender sorrow!

Seventy yards from the monastery wall, near a birch grove, in the middle of a green meadow, there stands an empty hut, without doors, without endings, without a floor; the roof had long since rotted and collapsed. In this hut, thirty years before, the beautiful, amiable Liza lived with her old woman, her mother.

Lizin's father was a fairly prosperous villager, because he loved work, plowed the land well and always led a sober life. But soon after his death, his wife and daughter became poor. The lazy hand of the mercenary poorly cultivated the field, and the grain ceased to be produced well. They were forced to rent out their land, and for very little money. Moreover, the poor widow, almost constantly shedding tears over the death of her husband - for even peasant women know how to love! - day by day she became weaker and could not work at all. Only Lisa, who remained after her father for fifteen years, - only Lisa, not sparing her tender youth, not sparing her rare beauty, worked day and night - weaved canvas, knitted stockings, picked flowers in the spring, and took berries in the summer - and sold them in Moscow. The sensitive, kind old woman, seeing her daughter’s tirelessness, often pressed her to her weakly beating heart, called her divine mercy, nurse, the joy of her old age, and prayed to God to reward her for all that she does for her mother.

“God gave me hands to work with,” said Lisa, “you fed me with your breasts and followed me when I was a child; now it’s my turn to follow you. Just stop being upset, stop crying; our tears will not revive the priests.” .

But often tender Liza could not hold back her own tears - ah! she remembered that she had a father and that he was gone, but to reassure her mother she tried to hide the sadness of her heart and seem calm and cheerful. “In the next world, dear Liza,” answered the sad old woman, “in the next world I will stop crying. There, they say, everyone will be cheerful; I’ll probably be cheerful when I see your father, Only now I don’t want to die - what’s wrong with you?” "What will happen without me? Who will leave you with? No, God grant that first you will be settled in a place! Perhaps a good person will soon be found. Then, having blessed you, my dear children, I will cross myself and calmly lie down in the damp earth."

Two years have passed since the death of Lizin's father. The meadows were covered with flowers, and Lisa came to Moscow with lilies of the valley. A young, well-dressed, pleasant-looking man met her on the street. She showed him the flowers and blushed. "Are you selling them, girl?" - he asked with a smile. “I’m selling,” she answered. "What do you need?" - “Five kopecks?” - “It’s too cheap. Here’s a ruble for you.” Lisa was surprised, dared to look at the young man, blushed even more and, looking down at the ground, told him that she would not take the ruble. "For what?" - “I don’t need anything extra.” - “I think that beautiful lilies of the valley, plucked by the hands of a beautiful girl, are worth a ruble. When you don’t take it, here’s five kopecks for you. I would always like to buy flowers from you; I would like you to pick them just for me,” Lisa gave the flowers, took five kopecks, bowed and wanted to go, but the stranger stopped her by the hand; "Where are you going, girl?" - “Home” - “Where is your home?” Lisa said where she lived, said and went. The young man did not want to hold her, perhaps so that those passing by began to stop and, looking at them, grinned insidiously.